An offshore wind Marshall plan for Europe: Offshore wind at a crossroads

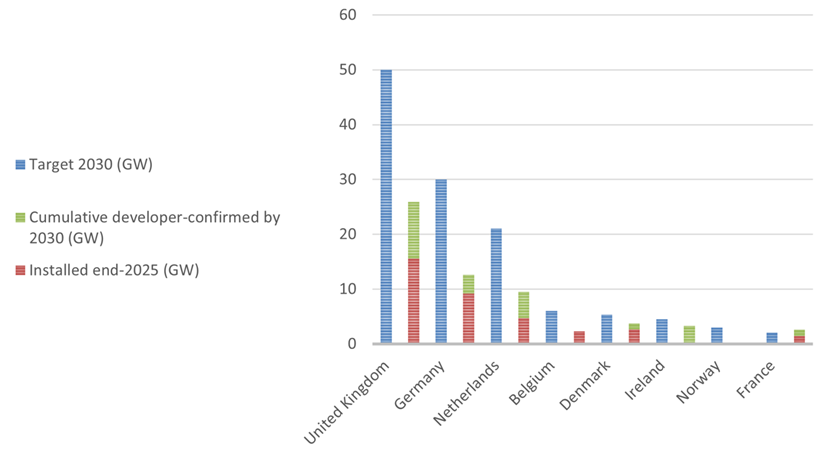

As European heads of state and energy ministers prepared for the third North Sea Summit on 26 January in Hamburg, it was clear that the offshore wind targets agreed on at the previous summit in Ostend will be missed by a wide margin in 2030 (roughly by 50%, at 60 GW rather than 120 GW).

The reasons for this are not that offshore wind is not feasible. Rather, the reasons are that offshore wind is not being promoted systematically and strategically in Europe – in sharp contrast to other regions of the world. The recent Hamburg declaration addresses some of the main issues that we have analysed below and that we feel led to the shortfall of the build out.

Three countries in particular (GB, DE and NL) are the main drivers in European offshore wind - and if they are falling short of their ambitions, this will have an impact on the future success of the entire industry in Europe.

What is causing projects to fail today in Europe? There are essentially four points to mention here:

- Higher financing and capital costs

- Higher supply chain cost (driven by demand and raw material price increases)

- Changes in the electricity market with an increasing number low price hours, coupled with a sluggish rise in electricity demand

- Insufficient standardization of construction methods – limited thinking in terms of large-scale industrial production.

This situation is leading to offshore wind projects becoming increasingly unattractive for individual project developers and also the supply chain. Especially compared to potentially other energy projects in their pipeline– such as battery storage or gas-fired power plants – leading to alternative projects being prioritized and offshore wind being delayed.

But why do we need offshore wind in Europe? The simple answer is that it is the only way to further advance decarbonization with high full-load hours and make Europe independent of fossil fuel imports in an increasingly power-political world. In addition, the further development of the technology continues to offer significant potential for industry in Europe to secure a final domain of clean tech leadership for European companies.

Only a systemic rethink will make goals such as those set in Ostend achievable and therefore DNV is looking forward to the Hamburg dialogue.

What needs to be done in concrete terms: systemic planning of expansion instead of volume targets. Governments must create the landscape that invites investment for offshore wind:

- The industry along the value chain needs to be given an annual orders base (clear annual auctions and volume) to enable economies of scale and cost reductions. Attractive Auction Criteria are essential to achieve reliable production capacity utilization

- At the same time, European standards must be defined and implemented that enable large-scale production for the whole European market

- Developers require certainty regarding the returns to be achieved from offshore wind through a balanced tender design. Regarding a subsidy regime, this can only be guaranteed through CfDs in such a way that sufficient planning security is ensured and offshore projects are also attractive compared to other investments. At the same time, the focus must remain on electrification—this reduces the cost of CfDs for the state as electricity demand rises

- In terms of industrial policy, accompanying measures are needed to further develop the supply chain in Europe: The airspace industry and what has been achieved with Airbus can be seen as a blueprint for a successful implementation

- In addition, project requirements, especially those relating to capital-intensive aspects, must be harmonized as much as possible across Europe to reduce costs and make the products attractive for export.

What we see in the declaration is a framework that if it is really enables will certainly drive the advancement of offshore wind. Still the proof will be in real legislative action in the member states taken soon and their improved coordination as agreed in Hamburg. The postponement of the next German offshore tender as it has been announced on the 28th of January shows that the importance of reliable schemes in such a capital-intensive business might be still not understood. Let's hope that we will not talk about an even wider gap when the next North Sea Summit comes up.

It's important to remember that Europe has the size and power to jointly turn the North Sea into a “power hub” that aims not only to produce electricity but also stands for energy independency within sight - let's not miss this opportunity.