This region consists of all African countries except Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt, which are included in the Middle East and North Africa region.

| 2024 | 2060 | |

| Population | 1.3 billion | 2.5 billion |

| GDP* | 5.9 trillion | 23.2 trillion |

| GDP/person | USD 4 600 | USD 9 360 |

| Primary energy use | 25.4 EJ | 45.8 EJ |

| Primary energy use/person | 20.2 GJ | 18.6 GJ |

| CO2 emissions** | 0.9 Gt | 1.5 Gt |

| CO2 emissions/person | 0.7 tonnes | 0.6 tonnes |

*All GDP figures in the report are based on 2017 purchasing power parity and in 2023 international USD.

**Energy- and process-related CO2 emissions, after CCS and DAC.

The region offers strong fundamentals – abundant land, minerals, renewable resources, a young, entrepreneurial population, and the world’s largest free trade area – but modern energy systems are underdeveloped. Balancing the energy trilemma – affordable, secure, sustainable energy – will be central in driving inclusive development.

Current situation

Fossil fuels

in primary energy supply (biomass makes up 53%)

People

without electricity in the region

of global renewable energy investment

from SSA in the last 20 years

Losses (USD)

caused by Nigeria's 2022 floods

- Fossil fuels account for 43% and biomass (predominantly used in cooking and water heating) accounts for 53% of primary energy supply in 2024. Roughly four out of five households lack access to clean cooking (IEA, 2025).

- Sub-Saharan Africa holds 85% of the global population without electricity – 588 million people (World Bank, 2025a). One-third live in Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Ethiopia (IRENA, 2025). Due to unreliable grids, back-up generators are widely used, with high diesel costs (IFC, 2019).

- Vast solar, wind and hydropower potential offer great opportunities for renewable power. The gap between financing needs and actual flows remains substantial. Over the last 20 years, the region accounted for 2% of global renewable energy investments (UNSDG, 2025). Installed renewables capacity reached 71 GW in 2024.

- Climate change risks range from erratic precipitation patterns to severe drought. Torrential rains and severe flooding affected nearly seven million people in 2024 (UNOCHA, 2024) and insurance coverage is limited. Nigeria’s 2022 floods caused USD 4.2 billion losses (German Watch, 2025).

Pointers to the future

- Energy agendas focus on developing oil and gas reserves, transitioning cooking away from conventional biomass, and expanding renewables in the electricity system – driven increasingly by falling solar and battery costs.

- With limited public funding and financially constrained utilities, liberalized markets will be key to attracting electricity investments. Countries like Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania, and Uganda, are reforming their electricity sectors to enable independent power producers, supported by the African Union’s work on regulatory harmonization and the African Single Electricity Market (AfSEM) framework for regional integration and cross-border electricity trade.

- Power projects are benefitting from Chinese technologies and investments, particularly through Belt and Road initiatives which surged to USD 30.5 billion in H1 2025 from USD 6.1 billion in H1 2024 (Nedopil, 2025).

- High financing costs make concessional finance critical for catalyzing private capital, with the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) playing a role in risk mitigation (DNV, 2025). However, a 7% drop in international aid (OECD, 2025), the dismantling of USAID’s Power Africa, and the US withdrawal from JETPs with South Africa and Senegal, complicate access to finance.

- Initiatives like the EU Scaling up Renewables in Africa campaign, in collaboration with Mission 300 of the World Bank and African Development Bank (EC, 2025), aim to support energy access. Distributed solar is also growing organically, especially among commercial users seeking alternatives to unreliable and costly grid power.

- Hydrogen ambitions are at early stages with governments seeking partnerships. Most plans are export-oriented and driven by global partners given fiscal limitations and lack of national subsidies for capital-intensive projects.

The energy transition indicators

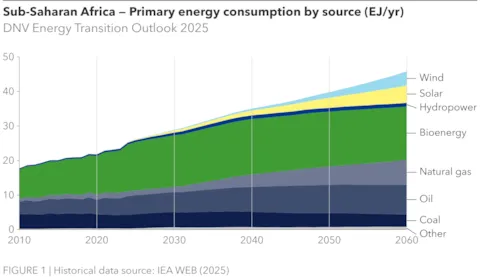

Primary energy consumption (EJ/yr)

Bioenergy dominates Sub-Saharan Africa’s primary energy mix, constituting over half the energy consumed last year. 60 percent of the population use inefficient traditional biomass combustion for cooking and water heating. Bioenergy generation will increase slightly towards 2060, but by much less than population growth. The fastest growing energy sources are natural gas, solar power, and wind as cooking and water heating switch to gas and electricity grids decarbonize.

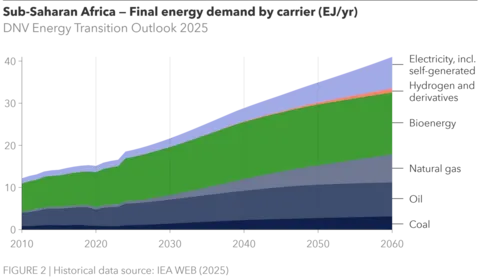

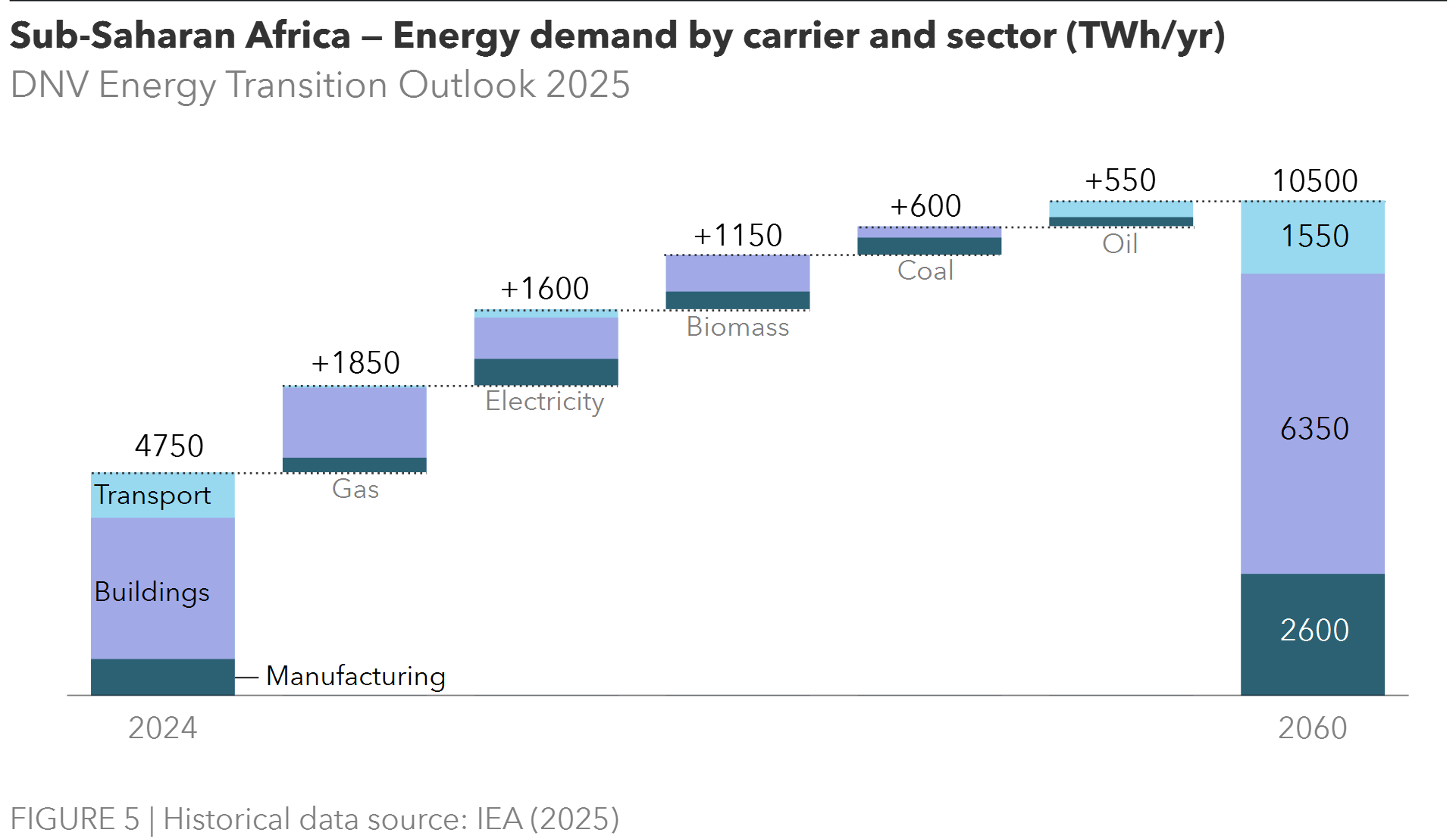

Final energy demand (EJ/yr)

Final energy demand is similarly dominated by biomass. Over the coming decades, more efficient natural gas and electricity will phase into the demand mix. By 2060, natural gas’s share quintuples from 3% to 16% and electricity’s doubles from 9% to 18%. Oil demand almost doubles, driven by increases in the number of vehicles enabled by a growing GDP. Total fossil fuel share rises from 35% to 43%.

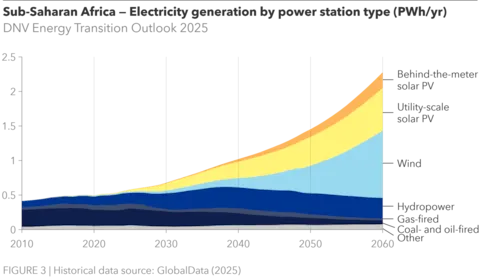

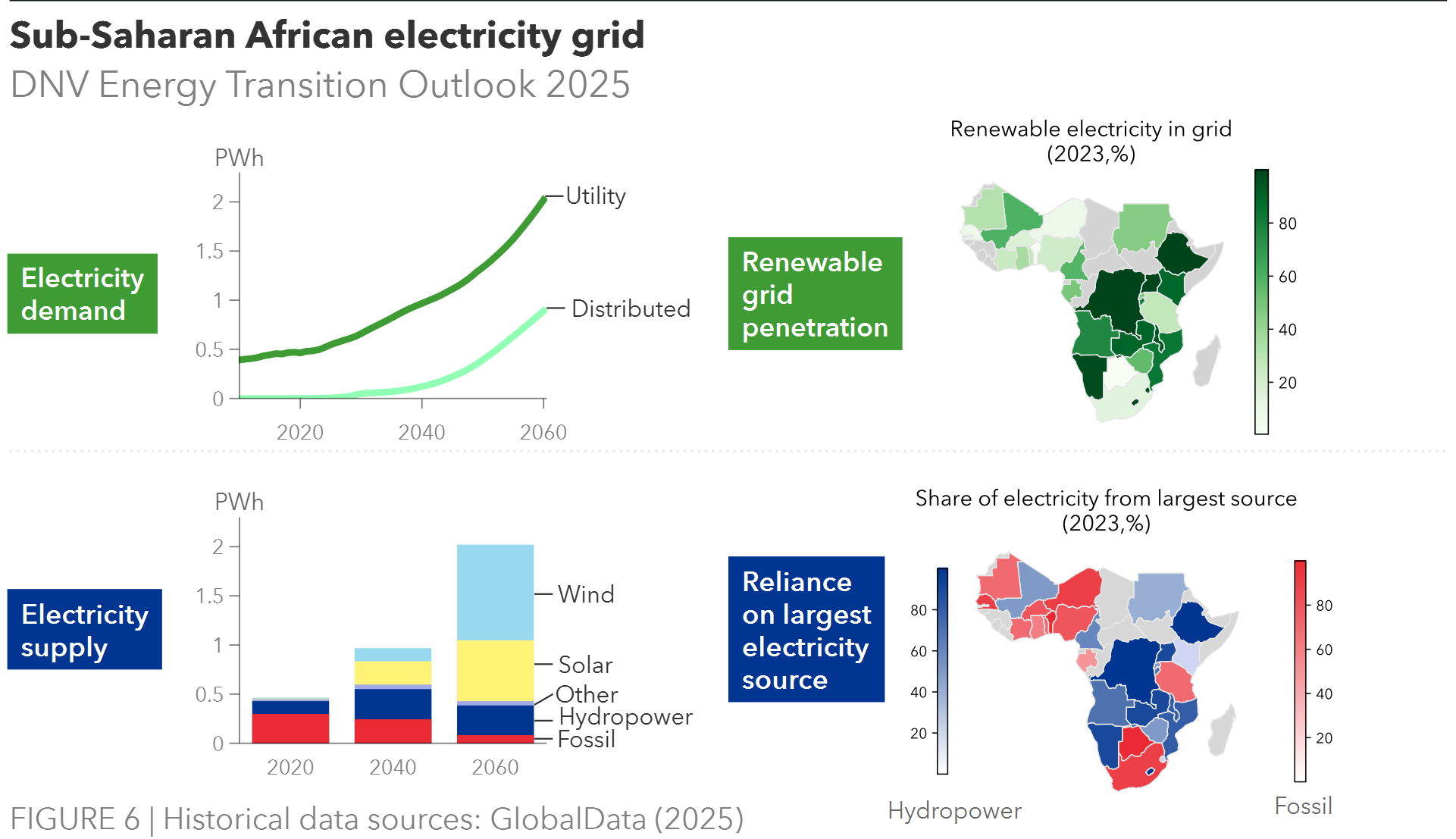

Electricity generation (PWh/yr)

Electricity generation in Sub-Saharan Africa quadruples to 2060, and the electricity mix changes dramatically from 60% fossil fuel today to only 3% in 2060. Hydropower’s share doubles, but the real growth comes from solar and wind, which increase to 45% and 35% of the electricity mix, respectively. Almost half of generated solar power will be distributed generation providing minimal electricity access to 60% of the population and displacing diesel generators.

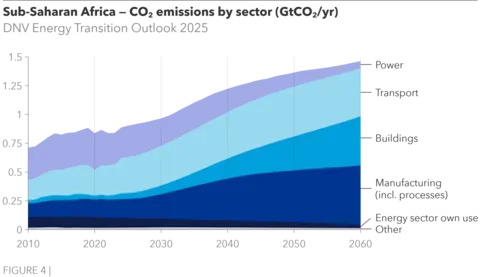

Carbon dioxide emissions by sector (GtCO2/yr)

Unlike in all other regions, emissions in Sub-Saharan Africa will keep increasing and will be 65% higher in 2060 than in 2024. However, on a per capita basis they will remain comparatively low. Power will decarbonize, producing only 4% of emissions in 2060. Growth in road transport emissions will be tempered by electric two- and three-wheelers and passenger vehicles. Emissions growth will be driven mostly by gas use for cooking, water heating, and manufacturing, particularly cement making.

Electrification is ongoing but meaningful change is dependent on access to clean cooking

Mission 300 is an African Union and World Bank initiative to connect 300 million people in Africa to electricity by 2030. If successful, this would halve the population living without access on the continent. In January 2025, 30 heads of state gathered in Tanzania to track progress towards the goal (World Bank, 2025). At the event, loans worth USD 35 billion at below market interest rates were announced to facilitate power generation and transmission projects (Bearak, 2025). Our analysis shows that despite the investment the initiative is unlikely to achieve its target and that the share of those living without electricity access will fall just 2024 and 2030. We expect almost all of this reduction to come from small off-grid solar installations.

The spread of off-grid solar systems represents crucial progress for Sub-Saharan Africa’s residents’ access to lighting and charging. However, these systems cannot displace biomass in residential cooking or water heating, which in 2024 constituted 78% of all biomass energy demand. This is because small off-grid solar is not sufficiently generative or consistent to run electric stoves. As such, this development will do little to expand access to clean cooking.

The residential use of biomass has extreme socioeconomic and environmental impacts. Smoke inhalation contributes to 815 ,000 premature deaths in Africa annually and predominantly women and girls spend hours each day gathering fuel, often at the detriment to their education and income. Biomass is a very inefficient fuel; only 5% is converted to useful energy during cooking. It’s gathering and production results in deforestation at a rate of 1.3 million hectares annually (IEA, 2025).

Gas and electricity use will expand over the coming decades even as biomass demand continues to grow. By 2060, we expect electric and gas residential cooking and water heating demand to increase 10-fold and 20-fold, respectively. In the same period, biomass demand will increase by To displace biomass use, gas distribution networks are needed across the region. The technology exists to expand clean cooking across Africa; the speed of the expansion will depend on political and financial prioritization.

Ethiopia leads electric vehicle uptake

In countries with significant available electricity resources, electric vehicles (EVs) are becoming more popular. In Ethiopia, EV adoption has tripled in two years since sales taxes were drastically reduced. In 2024 over 60% of new vehicles sales were electric. Ethiopia’s hydropowered electricity is abundant and cheap to produce, and the government is aiming to reduce the USD 4 billion dollars it spends annually on imported fuel (Ogheneochuko, 2025). In the wider region we expect passenger EV sales to take off in the 2040s, delayed compared to other areas due to challenges with grid reliability and charging station roll out. However, as an early adopter, Ethiopia, shows the potential of the technology.

Vehicle sales in Sub-Saharan Africa have historically been dominated by second-hand cars from Japan, Korea, and China. As these regions transition to EVs, it would be expected that the vehicles bought and driven in Africa will also transition. However, origin countries may be hesitant to export battery base materials in used cars.

Regional variation in power mixes

Sub-Saharan Africa can be divided into countries that produce and consume domestic fossil fuels and those that do not. Fossil-fuel producing countries include South Africa, where 85% of its electricity mix is coal, and Nigeria, where 73% of its electricity is gas-fired (Global Data, 2025).

Most countries in the region that do not produce fossil fuels consume little in their electricity mixes and have high renewable penetration. This is partially because per-capita electricity demand is the lowest in the world and electricity’s share of the energy mix is only 9%. However, it is also because countries without domestic resources are hesitant to import expensive fossil fuels and large renewable power projects have been operating in the region since around the end of colonialism.

The largest of these renewables is hydropower, which in 2024 accounted for 30% of Sub-Saharan Africa’s electricity mix. Countries across the region rely on hydropower generated by dams on Africa’s many large rivers. Notably, Zambia and Zimbabwe share the Kariba dam near Victoria Falls, and Uganda, Ethiopia and Sudan have dams on the Nile River.

While some hydropower dams, particularly in Southern Africa, have struggled over recent years due to increasingly inconsistent rain patterns (Savage & Chingono, 2024), overall hydropower is expected to increase in the region in the near and medium terms. Large projects and associated transmission infrastructure are underway, and we expect hydropower generation to double by 2040.

Several countries in the region have electricity mixes which are over 90% renewable, and almost all have achieved this through hydropower. The exception is Kenya, whose largest source of electricity is geothermal power. In combination with hydropower and a growing proportion of solar and wind power, Kenya’s electricity mix is 90% non-fossil. The country is aiming to be 100% renewable by 2030.

Given rising hydropower, solar, and wind, it is unlikely that Africa’s development will be fossil-fuelled, particularly in countries that do not have established domestic fossil-fuel production. Sub-Saharan Africa does have significant fossil-fuel reserves, but much of it will be too expensive to extract and will ultimately be left in the ground (Leke et al, 2022).

South Africa’s electricity generation is an outlier; the country accounts for 44% of the region’s supply. If South Africa is excluded from the region, the remaining electricity supply is 57% non-fossil, of which 51% is hydropower. In 2023, coal supplied 85% of South Africa’s electricity, but this has been trending downwards since 2010, when coal accounted for 94%. Quickly growing onshore wind and solar power are generating sufficient electricity to replace coal and cover growing demand. Distributed solar is rapidly expanding, and there is now more installed distributed than utility capacity (Kuhudzai, 2024). While these installations were initially a response to load-shedding, they are continuing despite improvements in grid reliability.

Interconnectors and energy market liberalization

Sub-Saharan Africa is split into five separate electricity power pools; West, North (Mahgreb), Central, East, and Southern. By 2040, these five power pools will be combined into the African Single Electricity Market (AfSEM). Dozens of interconnector projects will be completed in the 2020s and 2030s to realize AfSEM (AEEP, 2023). Notably, the Angola–Namibia (ANNA) Transmission Interconnector will connect the Southern African Power Pool (SAPP) to the Central Africa Power Pool (CAPP), while the Zambia–Tanzania–Kenya (ZTK) Interconnection Project will connect the Southern African Power Pool to the Eastern Africa Power Pool (EAPP).

AfSEM will strengthen not only the electricity grid throughout Africa but also regional collaboration and interdependence. The key purpose of several of the planned interconnectors will be to transport power from new and existing hydropower dams across borders and to cities and industrial hubs with high power demand (AfDB, 2023).

Another major ongoing development is the shift from single government buyers operating under long-term power purchase agreements (PPAs) for electricity production to a more open market such as in Europe. This transition has started in South Africa, where in January 2025, the government began setting up the South Africa Wholesale Electricity Market (SAWEM) which should operate as an open and competitive market from 2031.

Following South Africa, both Kenya and Zambia have begun the regulatory process to open their electricity markets. In a transitionary stage, both countries are enabling independent power producers (IPPs) and large electricity consumers to trade directly via existing grid networks in a process known as ‘wheeling’ (Bowmans, 2025). The same three countries are considering unbundling their state electricity companies into separate generation, transmission, and distribution entities in an effort to increase efficiency (Felekis et al, 2025).

A more open electricity market enables competitive pricing and more flexible contracts for IPPs, lower prices, more choice of electricity supplier for consumers, and improved stability and efficiency for governments. It also encourages much needed capital investment in energy infrastructure from the private market and enables regional interconnectivity.

However, both transmission and distribution grids across Africa require significant investment for expansion and maintenance to support an expanded, open electricity market. This will be particularly true if countries intend on enabling behind-the-meter prosumer behaviour from customers, which reduces the distributor’s total income.

Electricity suppliers in Sub-Saharan Africa typically earn most of their income from large industrial consumers. Most of their costs are incurred from supplying rural households, which consume very little electricity and often receive government subsidies. To raise income, suppliers must increase the tariffs charged to industrial consumers. This is motivating industry to install off-grid rooftop solar panels, reduce their reliance on the grid but this change also reduces supplier revenue.

Sub-Saharan Africa’s grid suffers from similar problems to elsewhere in the world; investment is lower than required, supply-chain challenges, particularly for transformers, lead to project delays and grid connection can be a lengthy and bureaucratic process. South Africa has recently changed from a first-come first-served connection queue to a first-ready first-served system, which is helping to prioritize financially and technically feasible projects (Creamer, 2023)

Between 2024 and 2060, we expect nine million circuit-kilometres of power line to be built in the region, with annual additions growing throughout. However, in 2025 only three quarters of desired grid capacity additions were possible, a limitation resulting from supply constraints. Increasing global manufacturing capability should resolve this issue by the end of the decade.

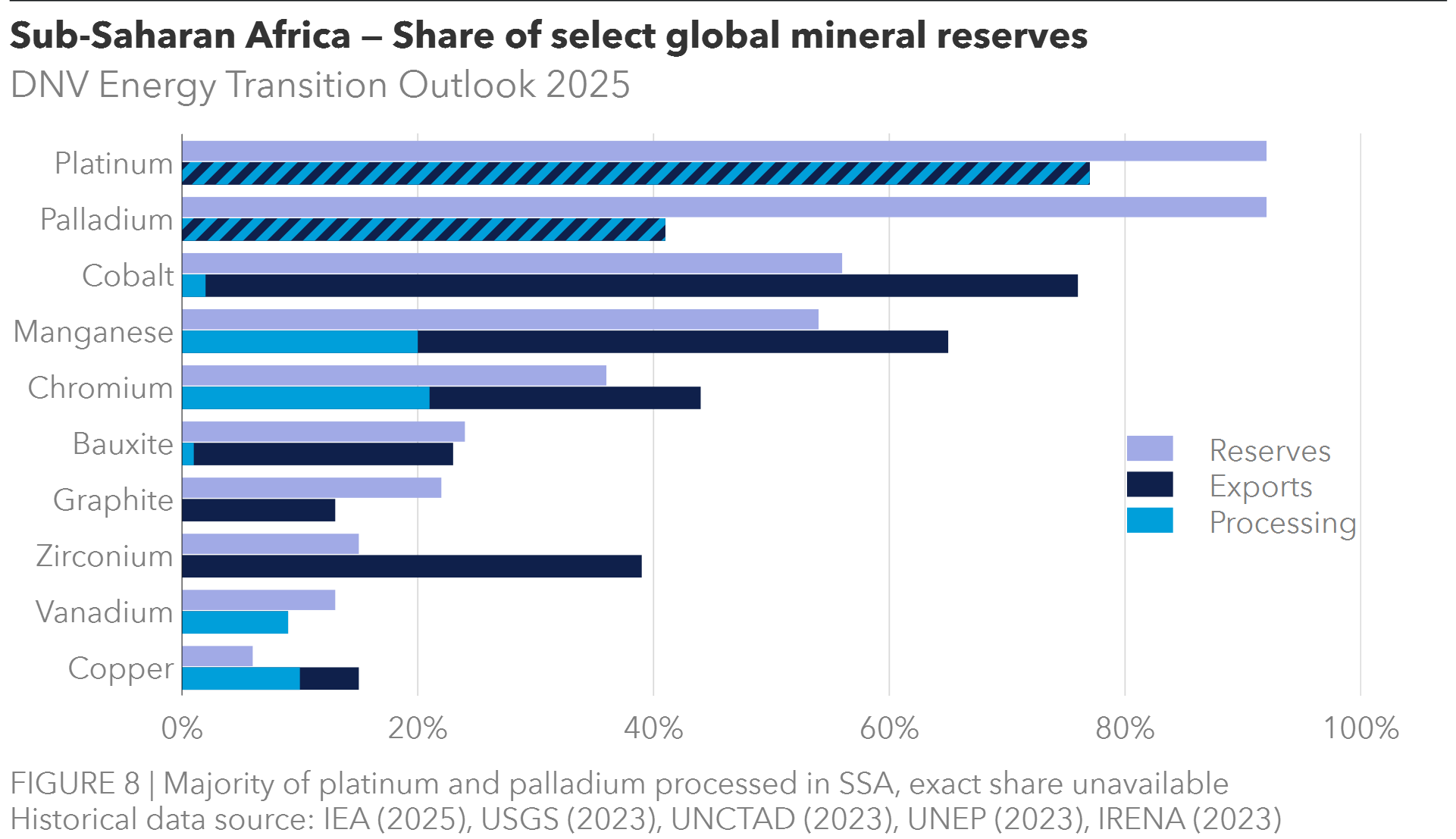

Africa’s resources vital to energy transition and the continent’s development

Critical minerals will play a growing role in the energy transition, and Sub-Saharan Africa’s reserves are among the largest in the world. Mineral extraction currently accounts for around 10% of GDP in resource-rich countries (IMF, 2021). Globally, revenues from four key minerals – copper, nickel, cobalt and lithium – are expected to reach USD 16 trillion over the next 25 years, of which around 10% will be generated in Sub-Saharan Africa. This could raise the region’s GDP by 12% by 2050 (IMF, 2024).

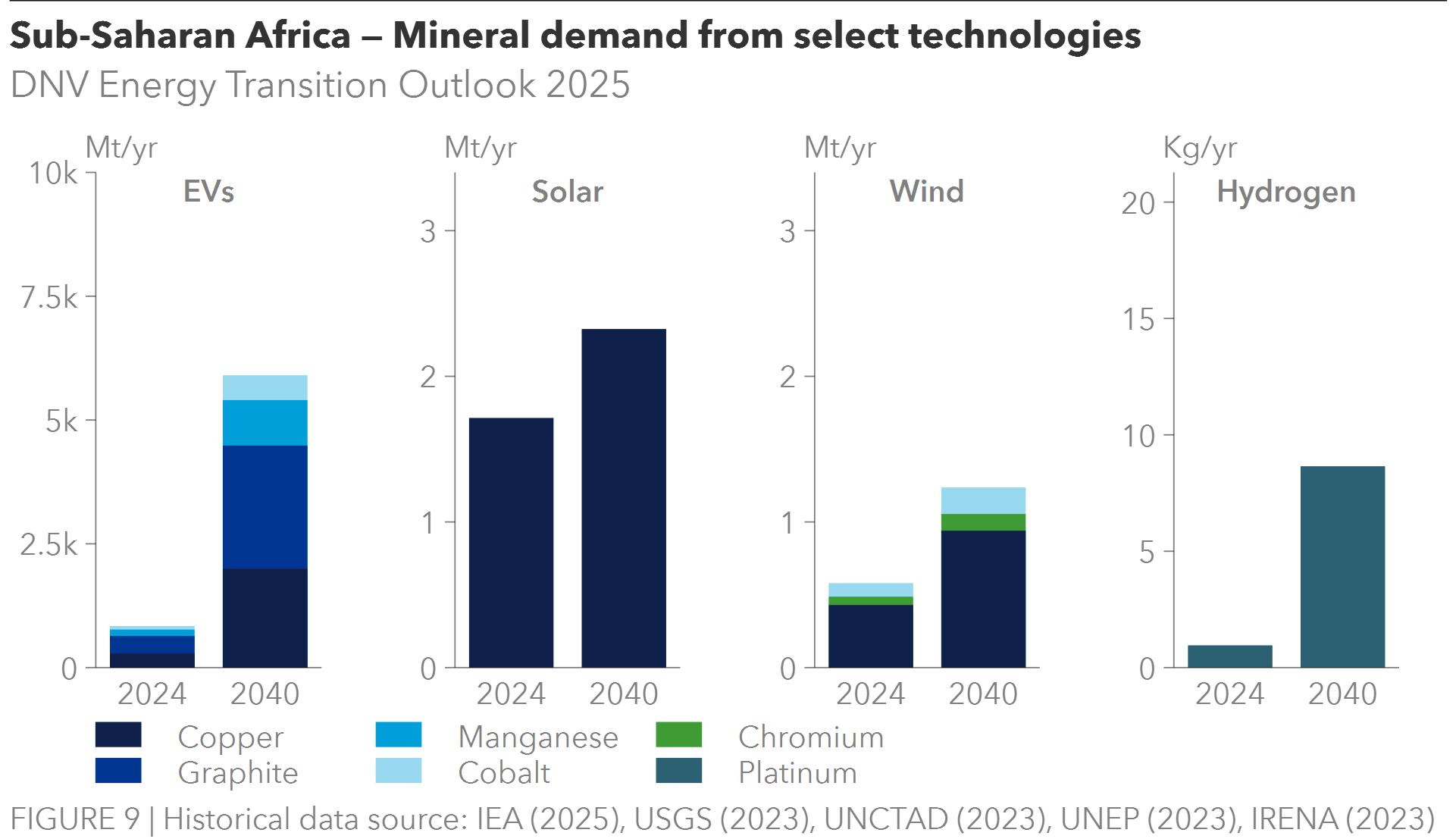

Assembling one EV demands 13 kg of cobalt (IEA, 2021), 70% of which originates in the DRC. We forecast global annual passenger EV sales to increase seven-fold between 2024 and 2050, stabilizing from then onwards at around 110 million per year. Manufacturing EVs also demands copper, found in southern Africa, manganese from southern and western Africa, and graphite from East Africa. Demand for all these minerals will grow roughly in line with EV sales.

Similarly, each megawatt of wind or solar capacity demands three tonnes of copper and half a tonne each of manganese and chromium. With annual installations of these renewable technologies set to double by 2060, demand for the minerals can be expected to double as well. Expansion of grids and energy storage will demand even more copper extraction.

However, most countries in Sub-Saharan Africa process only a fraction of their mineral exports domestically, drastically limiting their potential profit (Kapekele, 2025). The Copperbelt found on the border between the DRC and Zambia is the second largest global reserve of copper and Zambia is the world's largest exporter of raw copper (OEC, 2023). Copper accounts for 70% of the country's export earnings (Bloomberg, 2025) despite only 20% of Zambia’s copper being processed in the country (OEC, 2023). The rest is exported, mostly to China, which is globally dominant in mineral extraction. Zambia’s exports of unrefined copper retain around 50% of the refined value.

Recently, Zambia has been pursuing increasing domestic processing capacity and plans to develop an EV battery supply chain alongside the DRC supported by US investment (DoS, 2022). Mines and processing plants across the continent have also been substituting diesel generators for solar and battery power, including one of the world’s largest copper mines; the Kamoa-Kakula Copper mining complex in DRC (CrossBoundary Energy, 2025). While this is primarily motivated by reduced operating costs, the shift contributes to the trend of a decarbonising manufacturing sector enabled by off-grid solar and batteries.

The DRC hosts 56% of the world's cobalt deposits and accounts for 76% of global exports, though only 2% of this is processed domestically. Cobalt is critical to both EVs and wind power, and demand is expected to at least double by 2030 and quadruple by 2060. However, the DRC has been marred by internal conflict for decades, and the proceeds from cobalt extraction have so far been unable to economically empower the population, 74% of whom live in poverty (UNICEF, 2022). Recent efforts by the government to organize artisanal miners, for whom the working conditions are typically poorest, have made little progress so far (Kulkarni, 2024).

The exception is South Africa which domestically processes most of its platinum exports. Platinum is used in hydrogen electrolysis. Several Southern African countries including South Africa and Namibia are investing in green hydrogen projects, pursuing not only decarbonization of transport and manufacturing but also job and skill creation throughout the mining-to-hydrogen process. The EU recently invested EUR 4.4 billion in Just Transition projects in South Africa, including platinum electrolysis production, renewable generation, and grid connectivity, all key ingredients for a green hydrogen value chain (Stur, 2025).

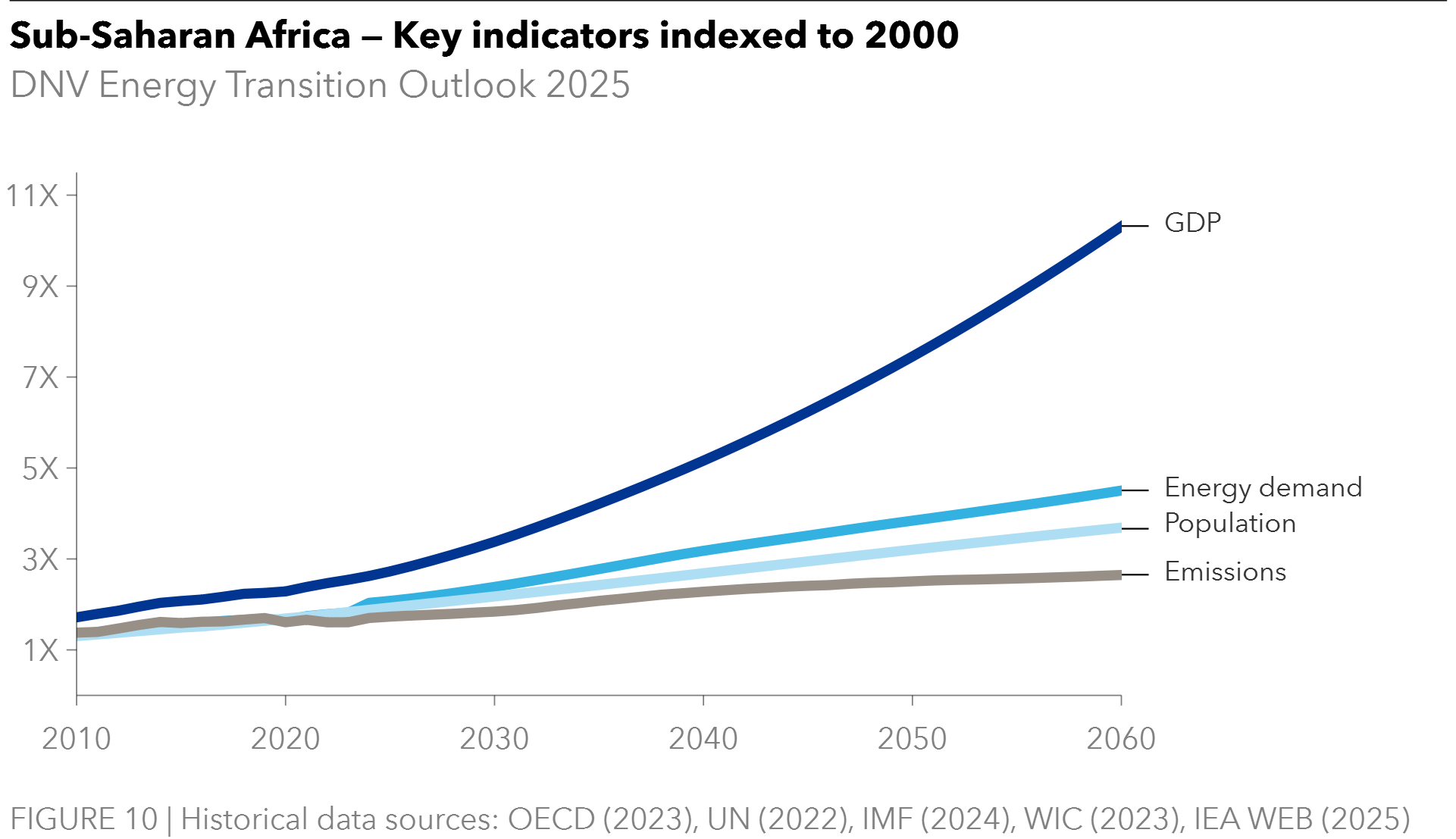

Decoupling emissions from development

Sub-Saharan Africa’s GDP is beginning to decouple from emissions but is doing so later than other global regions due to its earlier stage of development. While GDP increases four-fold between 2024 and 2060, emissions increase by only 60% in the same period. The point of decoupling will be reached when emissions reduce at the same time as GDP increases for a sustained period.

We do not expect absolute emissions to decline in Sub-Saharan Africa in our forecast period, but we do expect both the carbon intensity of energy and the emissions per capita to go down. This is because both energy demand and population will, like GDP, increase at a lower rate than emissions.

The cause of the start of this decoupling is that new demand will be met by other resources such as natural gas, which emits around half as much CO2 as coal for the same amount of energy produced. Coal’s contribution to total CO2 emissions will shrink from 45% in 2024 to 18% in 2060.

Sub-Saharan Africa will remain the region with the lowest absolute emissions until 2039, at which point it will emit more than OECD Pacific, a region which will then have a population nine times smaller. Correspondingly, Sub-Saharan Africa has the lowest emissions per capita throughout the forecast period.

Some carbon capture and storage will begin in Sub-Saharan Africa in the late 2030s, mainly within base materials manufacturing such as mineral processing, and within maritime. However, by 2060, only 2% of the region’s total CO2 emissions will be captured.

Africa’s rainforests and savannahs represent one of the world’s most significant carbon sinks. In more recent years, planting trees to offset emissions has been prominent in the region, though there have been doubts around the effectiveness and documentation of the process (West et.al. 2023).

Policy summary

A non-exhaustive list of sector policy initiatives, emphasizing the 2024 to 2025 period

Climate targets - Key countriesKenya, South Africa, Tanzania targets net zero by 2050, Ghana and Nigeria by 2060, Uganda by 2065. |

||

Sector |

Policy details and example initiatives |

Mechanism(s) |

|

Power |

> Renewable electricity plans combine national and regional approaches, including the African Union aiming for 300 GW renewable capacity by 2030 (January 2025) and the Mission 300 initiative with partners pledging over USD 50 billion to increase access (World Bank, 2025). > Renewable generation is promoted by national targets, including Nigeria for 36% and South Africa for 41% by 2030, and Kenya for 100% by 2030, leveraging geothermal and wind power. > Utility-scale projects are progressively procured through auctions on government issued tenders, with South Africa among the early adopters of both renewables and storage procurement for independent power production. > Behind-the-meter solar generation is organically rising due to grid inadequacies. > The 7% drop in international aid in 2024 (OECD, 2025), including cuts to USAID’s Power Africa, threatens progress and energy finance. |

Tenders/auctions for 20-year PPAs with state entities International finance |

|

> Coal phase-out policies are contingent upon support. The US terminated its membership of the International Partners Group (IPG) for Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs) withdrawing funding to support coal power phase out (March 2025) result in financial shortfall for Senegal and South Africa. > Tanzania, Mozambique, Angola, Gabon have plans for natural gas power expansion. |

International finance

Public-private investment partnership |

|

|

> Nuclear: South Africa plans to expand its nuclear capacity, with Uganda, Rwanda, Kenya, and Tanzania also showing interest. Financial constraints, long construction timelines and competitiveness of renewables limit development. But international financing is becoming more available with the nuclear funding ban lifted by the World Bank (June 2025). |

International finance Cooperation agreements, international partners |

|

|

Grids |

> Grid expansion plans combine national and regional approaches. > Grid deficiencies is a key focus area for international, concessional finance, such as Zafiri, an investment company launched by the World Bank and AfDB to derisk decentralized solutions, including mini grids; and Gridworks, funded by the British International Investment, providing long-term capital to transmission, distribution and distributed renewables. |

International finance

|

|

Hydrogen |

> Several countries (Angola, Kenya, Mauritania, Namibia, South Africa) aim to become hydrogen exporters. > International initiatives include the EU Global Gateway Initiative pledging USD 5.2 (€4.4) billion to South Africa to support renewable hydrogen production and platinum group metal exports to Europe (March 2025). Germany’s Development Bank (KfW) cooperates with South Africa’s Industrial Development Corporation to accelerate green hydrogen project rollout (July 2025). The government of Nigeria, APPL Hydrogen Limited (AHL) and LONGi Green Energy Technology Company (Chinese electrolyser and solar panel maker) formalized a €7.6 billion agreement, aiming to produce 1.2 Mt renewable hydrogen-based ammonia (February 2025). |

International finance International partnership |

|

CCS/DAC |

> South Africa has CCS interest as part of reducing emissions from coal-fired power generation. > Climeworks and Great Carbon Valley have a 1 MtCO2/yr DAC project proposed in Kenya (Sharma, 2023). |

No concrete policy No public funding programmes |

|

Transport |

> Promotion of electric mobility is building through a combination of financial incentives and partnerships. The electric bus market is expanding through public procurement. > Several countries announce biofuel blend targets to gradually increase in road transport, dependent on production capabilities. Nigeria for 10%, Ghana for 20% by 2030 biofuels while South Africa aims to increase its biofuel blending mandate to 45% for ethanol vehicles by 2060. |

Public procurement Reduced/abolished import duties Public-private pilots Biofuel-blending mandates |

|

Manufacturing |

> South Africa’s Industrial Policy Action Plan (2024) outlines decarbonization options. The Green Energy Efficiency Fund of the Industrial Development Corporation in partnership with the German Development Bank (KfW) was launched to advance its implementation with concessional loans to efficiency and self-use renewable projects (August, 2025). |

International finance International partnerships |

|

Buildings |

> Focus on energy efficiency is expanding, with minimum performance standards for space cooling now in place in Kenya, Nigeria, Rwanda, South Africa. in Kenya, South Africa, and Tanzania. > At COP29, the African Union and EU launched the African Energy Efficiency Alliance to support implementation of the African Energy Efficiency Strategy and Action Plan (November 2024). > Targeted electrification policies are nascent with the region primarily focusing on renewable power expansion. |

Standards International finance Public-private partnerships |

References

African Development Bank Group. (2023). The African Development Bank to boost electricity and transport infrastructure, value chain development and trade facilitation to spur regional integration in East Africa in 2023-2027.

Bearak, M. (2025). ‘The climate solution that doesn’t mention climate’. The New York Times. 31 January.

Chen, W. (2024). 'Harnessing Sub-Saharan Africa’s Critical Mineral Wealth'. International Monetary Fund.

Creamer, T. (2023). ‘Eskom’s new grid queuing rules governed by ‘first ready, first served’ approach’. Engineering News.

CrossBoundary Energy (2025). ‘Kamoa Copper and CrossBoundary Energy sign agreement for a groundbreaking baseload renewable energy system in the DRC.’

Department of State (2023). Support for the development of a value chain in the electric vehicle battery sector.

DNV (2025). Costly capital: Money for green megawatts in Sub-Saharan Africa. Authors: Anne Louise Koefoed & Sujeetha Selvakkumaran.

EC European Commission (2025). Scaling up Renewables in Africa.

Felekis, A., Chilufya-Musonda, B., and Baru, E., (2025). ‘Kenya, South Africa and Zambia: Open electricity market reforms – comparisons and lessons learned’. Energy in Africa.

German Watch (2025). Climate Risk Index 2025.

GlobalData (2025). Power: Capacity & Generation Database.

IEA (2025). Universal Access to Clean Cooking in Africa.

IEA (2021). ‘The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions’.

IFC ─ International Finance Corporation (2019). The Dirty Footprint of the Broken Grid.

IRENA (2025). Tracking SDG7 The Energy Progress Report 2025.

Kapekele. P, (2025). ‘Ending poverty and gangs: How Zambia seeks to cash in on the global drive for EVs’ Climate Home News.

Kuhudzai. R. J., (2024). ‘South Africa Now Has Over 12 Gigawatts of Wind & Solar Generation Capacity!’ Clean Technica.

Kulkarni. N, (2024). ‘Highlighting the Neglected Dimensions of the Energy Transition: The Case of Cobalt’ Climate Policy Lab.

Leke. A, Gaius-Obaseke. P, and Onyekweli, O. (2022). ‘The future of African oil and gas: Positioning for the energy transition’ McKinsey & Company.

Mitimingi. T, (2025). ‘Zambia Overcomes Severe Drought in 2024 to Boost Copper Output’. Bloomberg Law.

Nedopil, Christoph (2025). China Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Investment Report 2025 H1. Griffith University & Green Finance & Development Center (GFDC) of FISF, PR China.

OEC (2025). 'Zambia Country Profile'.

OECD (2025). International aid falls in 2024 for first time in six years, says OECD. April 16.

Ogheneochuko, I.I. (2025). ‘Ethiopia electric vehicle adoption triples in two years on policy drive’ Energy in Africa.

Savage, R., and Chingono, N. (2025). ‘‘Levels are dropping’: drought saps Zambia and Zimbabwe of hydropower’. The Guardian.

Stur, B. (2025). ‘President von der Leyen in South Africa unveils €4.7 billion Global Gateway package’ European Interest.

Thales A. P. West et al. (2023). ‘Action needed to make carbon offsets from forest conservation work for climate change mitigation’ Science.

The Africa-EU Partnership (2023). Regional Electricity Interconnection and Market Integration in Africa is Taking Huge Strides Forward.

UNOCHA ─ United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (2024). West and Central Africa: Flooding Situation Overview - as of 5 October 2024.

UNSDG ─ UN Sustainable Development Group (2025). Decoding Africa’s Energy Journey: Three Key Numbers. January 27.

US Poverty Data (2025). DRC Poverty in Numbers: How a Resource-Rich Country Remains Poor.

World Bank (2025a). An Evaluation of the World Bank Group’s Support to Electricity Access in Sub-Saharan Africa, 2015–24.

World Bank (2025b). ‘An Overview of Mission 300’.

Yontcheva, B., Devlin, D., Devine, H., Beer, S., and Suljagic, I. J. (2021). ‘Tax Avoidance in Sub-Saharan Africa’s Mining Sector’ International Monetary Fund.