This region consists of South Asian countries: India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bhutan, and the Maldives. India and Pakistan together account for 80% of the region’s energy use.

| 2024 | 2060 | |

| Population | 1.9 billion | 2.4 billion |

| GDP* | USD 17.9 trillion | USD 56.8 trillion |

| GDP/person | USD 9200 | USD 23 800 |

| Energy use | 54 EJ | 97 EJ |

| Energy use/person | 28.3 GJ | 41.5 GJ |

| CO2 emissions** | 3.69 Gt | 2.5 Gt |

| CO2 emissions/person | 1.90 tonnes | 1.05 tonnes |

*All GDP figures in the report are based on 2017 purchasing power parity and in 2023 international USD.

**Energy- and process-related CO2 emissions, after CCS and DAC.

The most populous of the 10 regions: 1.9 billion people today, rising to 2.4 billion by 2060. With GDP per capita tripling as well, one could expect runaway regional energy demand, but in fact it rises moderately by 74% to 73 EJ/yr, owing to the rising proportion of efficient, renewable based-power in the energy mix.

Current situation

Renewables

in power capacity in 2024

Fossil fuel

in primary energy supply

Rise in CO2 emissions

between 2020 and 2024

Losses (USD)

due to monsoon floods in Pakistan in 2022

- Renewables accounted for 41% of power capacity in 2024 in the region. Falling solar costs had Pakistan importing 90% of solar panels (over 16GW) from China in 2024. In 2024, India added 24.5 GW solar capacity (MNRE, 2025a). With increasing domestic manufacturing capacity, imports of cells and modules from China have dropped to around 60% of imports from around 90% previously (AngelOne, 2025).

- Fossil fuels still dominate primary energy (80%), with high import dependence: 90% of oil, 45% of gas, and 30% of coal. To support affordability, fossil-fuel consumption subsidies in 2022 reached 2% of GDP in India, 8% in Pakistan, and 6% in Bangladesh (IEA, 2023).

- CO2 emissions rose 35% between 2020 and 2024 due to economic, population and energy demand growth, particularly cooling, though per capita energy use remains low.

- Climate risks include sea-level rise, cyclones, heat and water stress. Monsoon floods caused USD 15bn damage in Pakistan (2022), while Bangladesh faces USD 3bn in annual losses (German Watch, 2025). At 2°C warming, India’s annual climate cost is projected to exceed 6% of GDP (World Economic Forum, 2024).

Pointers to the future

- Energy expansion choices are primarily driven by economics. Outside India, government subsidies for capital-intensive projects are limited. Renewable electricity remains a priority due to falling costs, though coal continues to play a role for energy security reasons. Plans to switch from coal to gas face challenges due to import dependence and LNG price volatility driven by geopolitics.

- India targets net zero by 2070, aiming to reduce carbon intensity of GDP by 45% and achieve 500 GW of cumulative electric power capacity from non-fossil fuel sources by 2030. The Viksit Bharat 2047 vision includes ambitious goals, such as 100 GW of nuclear and 1,800 GW of renewable capacity. Carbon capture initiatives are emerging, and the pursuit of renewable hydrogen and derivatives is deepening, driven by self-sufficiency goals.

- India’s industrial policy promotes domestic manufacturing to reduce technology import dependence and create jobs. The USD 2.76bn Electronics Component Manufacturing Scheme will bolster the electronics and IT industry within the umbrella Production-linked Incentive Scheme. Circularity in solar and battery technologies is emphasized under the MNRE’s Renewable Energy Research and Technology Development Scheme (RE-RTD) to strengthen indigenous capabilities.

- Pakistan’s solar transition is unfolding based in plummeting solar PV costs and imported Chinese technology, with close to 13 GW imports by Q3 in 2025. Rising residential and agricultural tariffs are driving a surge in distributed solar adoption as an alternative to costly fossil-based grid energy (Renewables First, 2025).

- India’s Neighbourhood First Policy supports energy expansion in neighbouring countries, including Nepal’s hydropower exports and regional power trade, among Bhutan, Nepal, Bangladesh, and itself, and renewable energy projects such as hydropower in Bhutan, wind and solar in Sri Lanka and Bangladesh, the latter targeting 20% electricity generation from renewables by 2030 and 30% by 2040, respectively to address energy shortages (Chambers & Partners, 2025).

- Afghanistan plans 4.5–5.5 GW renewable capacity by 2032 to improve energy access and security. There is vast solar (>200 GW) and wind (>60 GW) potential but only around 500 MW installed renewable capacity and just 30% of households connected to the grid. The Maldives, vulnerable to sea-level rise and extreme weather, is heavily reliant on diesel for electricity and aims to boost energy resilience with a 33% renewable electricity target by 2028.

The energy transition indicators

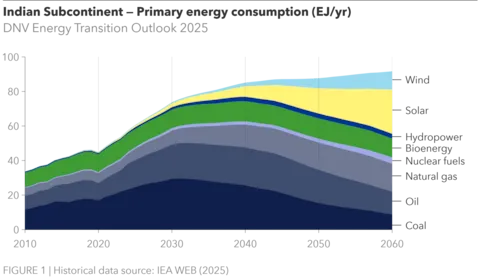

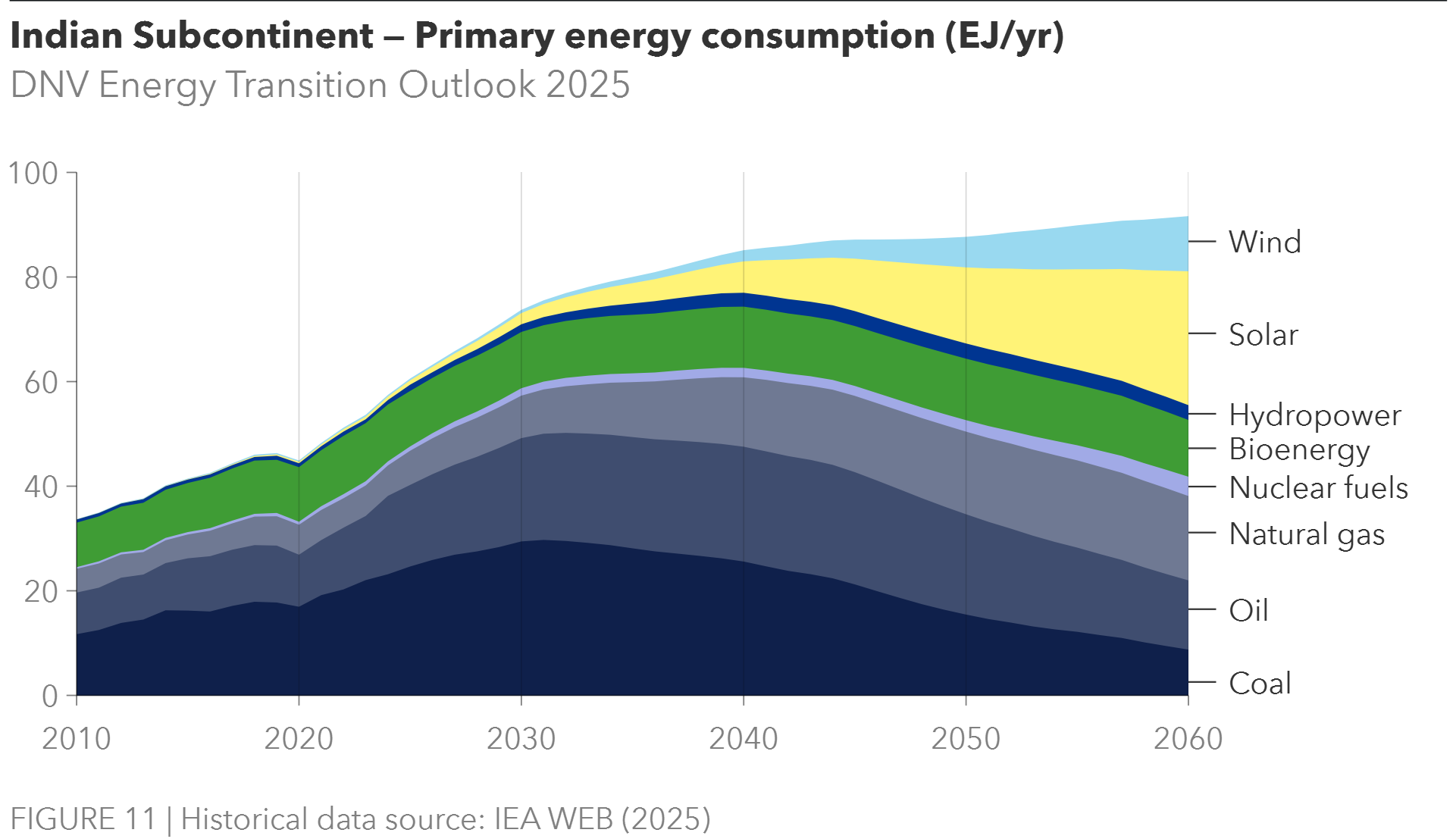

Primary energy consumption (EJ/yr)

Coal is the most abundant domestic fossil fuel available in the Indian Subcontinent, making up more than a third of energy consumption. The Energy Transition Outlook (ETO) forecasts a continual growth in coal consumption when it will peak and decline to just 10% of total final energy demand by 2060. Solar, wind, hydropower, bioenergy, and nuclear will supply more than half of the energy consumed by 2060, with oil and natural gas remaining a substantial contributor.

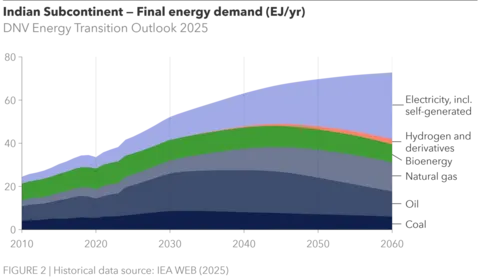

Final energy demand (EJ/yr)

A substantial portion of energy demand is met today by biomass, along with coal, natural gas, and oil. Due to continual electrification of products and services, electricity will be the most significant energy carrier in 2060, meeting 40% of final energy demand. Peak oil is also expected to occur in the 2040s, as EVs are forecast to hold the majority of new passenger vehicle sales by 2040.

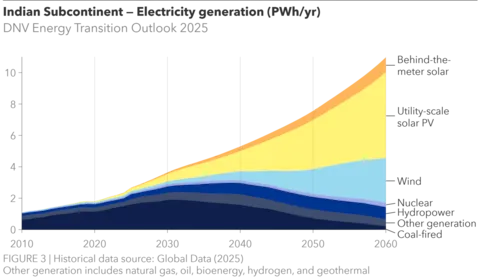

Electricity generation (PWh/yr)

Coal-fired electricity generation is forecast to peak in the 2030s, and a definitive transition to solar and wind is predicted, starting in the 2040s. By 2060, we expect electricity generation to be majority solar and wind at a combined 8.3 PWh/yr with moderate contributions from hydropower, nuclear, and behind-the-meter sources such as rooftop photovoltaics.

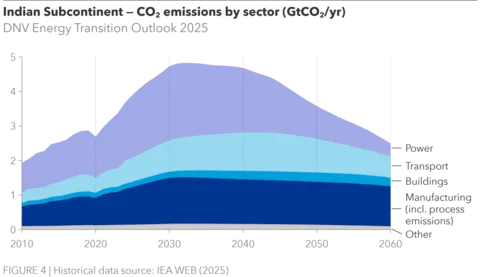

Carbon dioxide emissions by sector (GtCO2/yr)

Due to renewables progressively displacing coal in the 2030s, there is a clear peak and decline in greenhouse gas emissions from coal-fired power generation. Although less prominent, EV uptake in road transport also leads to emissions from combusting oil peaking then declining in the 2040s. Because manufacturing is hard to decarbonize, it becomes the biggest-emitting sector, accounting for 46% (1.2 GtCO2/yr) of the region’s total emission in 2060.

Energy transition in times of regional transformation

The Indian Subcontinent is the most populous of the global regions: 1.9 billion people today and an expected 2.4 billion in 2060. India alone comprises around 75% of the total population and its economic output, strongly influencing the region’s overall energy transition trajectory. Pakistan (255 million) and Bangladesh (176 million) are also relatively populous. The UN expects the regional population to grow by 500 million by 2060. India’s population peak is expected in the 2060s at 1.7 billion, declining to 1.5 billion people by 2100 (UN, 2024). Moreover, the World Bank’s Global Economic Prospects (GEP) reports India to be the fastest-growing economy today, forecasting 6.7% growth in both 2026 and 2027, far surpassing global growth of 2.7%.

Combined with the forecast growth in affluence, there are considerable challenges and opportunities in elevating the standard of living for households, managing climate risks, and investing in transforming the energy landscape. Demand for energy is expected to continue to increase in the coming decades, with the ETO forecasting a gradual plateauing in the 2050s at 70 EJ/yr. Currently, there is heavy reliance on domestic coal and fossil imports for energy consumption, thus significant investment into new, sustainable technologies is required for the subcontinent to achieve an energy transition.

Energy demand of Indian Subcontinent

Coal is the most abundant fossil fuel available for extraction in India and has long been a key energy carrier to meet demand from the subcontinent. Coal consumption will continue to increase up to 2030, when it will eventually peak and then decline slightly while remaining an important energy carrier and contributing 8% (6 EJ/yr) of the energy mix in 2060. Oil shows a similar trend: it must continue being imported, largely to meet transport energy demand, but will peak in the 2030s then fall back to current levels (11 EJ/yr) by 2060.

Increases in both population and the economy could lead to runaway regional energy demand if unmanaged, but we forecast moderate growth (74%) from 42 EJ/yr currently to 73 EJ/yr in 2060, due to the rising proportion of efficient, non-fossil power in the energy mix. Electrification is the cornerstone to both the energy transition and economic development, meeting 18% of final energy demand today and growing to 41% by 2060. But electricity punches above its weight, providing 54% of the useful energy in 2060.1 Hard-to-electrify processes are forecast to transition to low-carbon solutions such as bioenergy, hydrogen, and hydrogen-derivatives such as ammonia.

[1] ‘Useful energy’ is the energy that has been utilized for a specific purpose like work, heat, or light after accounting for conversion losses. ‘Final energy’ refers to energy directly delivered to users such as petrol, gas, or electricity before losses are incurred in end use.

Road transportation

Road has the highest energy demand of all transport subsectors, consuming 78% of the 9,400 PJ/yr used for all transport in 2024. Therefore, decarbonization and electrification trajectories for road transport greatly impact the emissions outlook for the whole sector. Acknowledging this, both India (FAME – Faster Adoption & Manufacturing of Electric Vehicles) and Pakistan (PAVE – Pakistan Accelerated Vehicle Electrification) have implemented policies focusing on boosting demand of EVs through subsidies, while Bangladesh is focusing on promoting domestic manufacturing of electric vehicles.

We forecast that EV uptake will be the fastest for two- and three-wheelers (mopeds and rickshaws), followed by the passenger then commercial market segments. This is especially important for the region as over 70% of households own a two- and three-wheeler rather than a four-wheel passenger vehicle. For two- and three-wheelers, 79% the sales market share will be electric in 2030, while passenger vehicles will reach the 50% milestone in 2040.

Although EV uptake is fast, especially for mopeds and rickshaws, oil will continue to be the main energy carrier to meet road transport demand until the late 2050s. This is due to older combustion vehicles being in use until they are retired. Therefore, peak oil demand occurs in 2043 at 12,600 PJ/yr before declining to 6,700 PJ/yr, nearly half (47%) of road transport energy demand in 2060.

Air transport and sustainable aviation fuels

Aviation is a notably hard-to-decarbonize transport subsector, for which electrification is not the ideal decarbonization pathway. Electric planes are expected to be viable only for niche, domestic short-haul flights that make up a small fraction of total flights. Instead, aviation is expected to use ‘drop-in’ replacement fuels to decarbonize. Sustainable aviation fuels (SAF) such as biokerosene, hydrogen, and e-fuels are forecast to gradually displace jet kerosene to meet demand from air transport. While we expect India’s goal of 15% SAF in domestic aviation by 2040 is unlikely to be met, the subcontinent will eventually have SAFs meeting 36% of transport energy demand by 2060. This is essential as aviation transport demand is expected to triple from 420 PJ/yr currently to 1,200 PJ/yr by 2060.

Buildings

Across the Indian Subcontinent's emerging economies, current building energy consumption is largely attributed to cooking and water heating, at 64% and 26%, respectively, of the sector’s total demand of 11,000 PJ/yr. Traditional biomass such as wood and charcoal provides 69% of the energy consumed currently. By 2060, buildings sector energy demand is forecasted to nearly double to 19,000 PJ/yr, with notable increases in appliances, data centres, and space cooling.

Cooling demand is expected to contribute a substantial portion of energy use for buildings, as steady rise in temperatures incentivize the increasingly urbanized and affluent households to acquire air conditioners. Space cooling will increase nearly nine-fold from 400 PJ/yr to 3,800 PJ/yr in 2060, when it will be the highest consumer of electricity for the buildings sector. However, we expect the grid mix in 2060 to be more than 90% of non-fossil origins.

Manufacturing sector

Manufacturing is another major hard-to-decarbonize sector, where many alternative energy sources cannot provide the high temperatures needed for industrial processes such as iron and steel production. As such, of the total sector demand of 16,000 PJ/yr, coal provides nearly 40%, followed by bioenergy at 23%. Coal and biomass provide much of the energy needed for industrial heat and iron ore reduction; however, we expect coal consumption to peak in 2032 and reduce by 30% by 2060. While biomass consumption will remain stable, cleaner-burning natural gas use is expected to increase. Hydrogen will account for 10% of iron and steel manufacturing energy demand in 2060 at 600 PJ/yr. Electricity currently meets 20% of manufacturing energy demand primarily for mechanical work, and we forecast that electricity uptake will continue to increase to make up 35% of total sector demand in 2060.

Indian Subcontinent energy supply and power capacity

The energy supply of the Indian Subcontinent has been predominantly coal, oil, natural gas, and traditional biomass. Coal is a domestically abundant fossil energy in India and has been the preferred source of energy supply. India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh import approximately 40% of the required energy supply, namely fossil fuels (IEA, 2025b,c,d). Coal, oil and natural gas combined (i.e. fossil fuels) currently supply 77% (44 EJ/yr) of primary energy for the region, and biomass contributes 19% (11 EJ/yr).

To decarbonize the fossil-rich energy supply, countries have set energy transition targets focusing on the electrical grid mix. India had a stated target of 50% non-fossil electricity capacity by 2030, which was achieved in 2025. Additionally, India is on track to install 500 GW of non-fossil power capacity by 2030 (MNRE, 2025c). Bangladesh and Pakistan are similarly setting 2030 non-fossil power generation targets at 20% and 60%, respectively. Sri Lanka has an even more ambitious goal of 70% non-fossil by 2030, and a phase-out of coal by 2042 (economynext, 2023).

Electrical grid and flexibility – enabler of future transition

To fully harness the potential of added renewable and non-fossil power, the electrical grid must also be modernized to prevent grid bottlenecks. India operates one of the largest unified electricity grids in the world, integrating five regional grids into a single synchronous national network. However, the Green Energy Corridor Overview, a comprehensive assessment of the readiness of the national grid, identified significant inadequacies in transmission infrastructure near renewable energy production sites. Additional transmission lines and substations are being built through the Intra-State Transmission System (InSTS) GEC-I scheme in renewable-rich states to integrate 24 GW of generation capacity (MNRE, 2023a). High voltage DC (HVDC) lines are also being built for long distance and inter-state transmission of power.

The increase in renewable power generation coming online on the grid must also be accompanied by energy storage to level out the increasing grid flexibility and ‘round-the-clock’ availability. The Indian Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) states that to meet India’s goal of 50% non-fossil by 2030, the national grid will require 82 GWh of storage generation by 2027, and ultimately 2,380 GWh by 2047 (MNRE, 2025d). MNRE India mainly highlights two storage solutions – pumped-storage hydropower (pumped hydro) and battery energy storage systems (BESS). India has currently 3.3 GW of operational pump storage while more than 40GW are at various stages of development and construction. Firms such as India’s AM Green have already secured 950 MW of pumped hydro storage with renewables to produce commercially viable green hydrogen (AM Green 2024). Pakistan is also expanding its BESS capacity, which currently has 7 GWh of storage, with another 20 MW pilot BESS project underway in Jhimpir (Yousafzai, 2025). India also launched a 40 MWh BESS project in New Delhi in April 2025. While we forecast that the individual stated national targets for pumped hydro will not be realized until the 2050s, rapid uptake of BESS in the 2040s will increase total regional storage to 5,800 GWh by 2050 and 16,800 GWh in 2060.

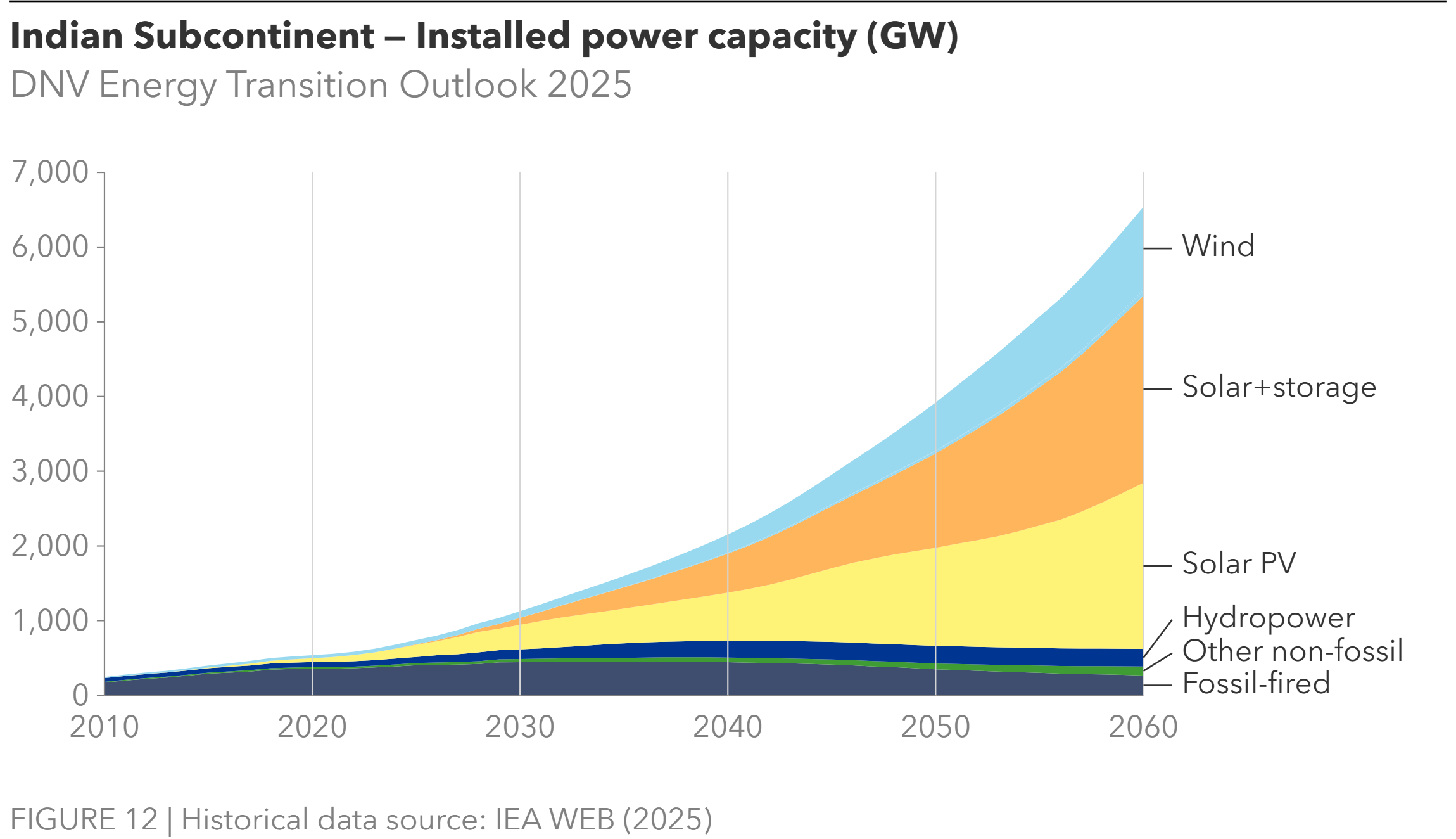

Non-fossil energy supply – renewables and nuclear

We forecast that across the subcontinent, renewable targets will be met, with a total share of non-fossil power capacity installation of 60% by 2030, totaling 680 GW. Non-fossils are forecasted to be predominantly solar photovoltaic (PV), solar plus storage, and onshore wind.

Solar – utility and rooftop photovoltaic

The decarbonization story of the Indian Subcontinent is primarily through solar power. Utility-scale solar installations are growing rapidly across the region. In India, solar contributed about 24.5 GW, accounting for nearly 73% of the total new capacity additions and 93% of new renewable capacity (MNRE, 2025e). Of the 660 GW of non-fossil installation expected in 2030, solar is forecasted to contribute half (330 GW). Moreover, solar power is forecasted to grow rapidly through 2060, when it will be 70% (3,700 GW) of the total non-fossil power mix.

In contrast, Pakistan’s solar boom is mainly ‘bottom-up’. Due to recent years of chronic power supply shortages and subsequent price increases, behind-the-meter (BTM) rooftop solar PV is in high demand (World Economic Forum, 2025). In 2024 alone, Pakistan imported solar PV panels equivalent to 17 GW of generation capacity. Increases in solar’s share in Pakistan has therefore been driven by decentralized, rooftop solar installations. India also has a goal of 10 million households fitted with rooftop solar by 2027, projected to add 30 GW of BTM capacity (MNRE, 2025f). These combined efforts are reflected in the ETO analysis, where the regional total of BTM capacity is forecast to be 90 GW by 2030, and growing at a rapid pace up to 1,050 GW in 2060, a 17% share of total installed capacity.

Wind – onshore and offshore

Wind energy is expected to play a significant role in the renewable energy supply mix, second only to solar PV. India currently has 50 GW of installed turbines along the western and southern coastline, stretching from Gujarat to Tamil Nadu (MNRE, 2025b). Pakistan currently has 1.8 GW of installed wind capacity, but it is estimated that total wind power potential in the country can be up to 350 GW (Renewables First, 2023). We forecast that the subcontinent will have 90 GW of onshore wind energy capacity by 2030. Offshore wind, fixed or floating, is not expected to play a significant role until 2050. In 2060, the region will have 76 GW of offshore wind power supply; however, onshore wind will be the primary source of wind energy, with 1,100 GW of installed capacity.

Bioenergy

Residential buildings (6,000 PJ/yr) and industry (3,700 PJ/yr) currently consume 97% of bioenergy. Traditional biomass such as wood and charcoal continues to be the primary source of cooking and water heating. Out of concerns for air quality and localized deforestation, there are campaigns to aid households to transition to improved biomass or LPG cookstoves (Fracassi et al., 2024). Biomass is forecast to be reduced drastically by 2060 to just 1,700 PJ, due largely to increased natural gas consumption.

Industrial heat is also heavily reliant on biomass in the region, at 44% of total manufacturing heat. Due to the hard-to-abate nature of manufacturing, we forecast biomass demand to grow steadily until 2050, when it peaks at 6,300 PJ then declines moderately to 5,700 PJ by 2060.

Road transport, which currently accounts for just 2% (177 PJ) of total bioenergy demand, could increase its uptake considerably. India recently announced a milestone of 20% bioethanol (E20) blend in the petrol supply five years in advance of 2030 (Ministry of Petroleum & Gas, 2025). Although petrol consumption applies to just 40% of total road energy demand, the E20 policy will affect two-wheelers and passenger vehicle markets, as they make up over 90% of the petrol user base (CEEW, 2025). India also has a 5% biodiesel blend mandate by 2030, which mainly affects the commercial segment (Ministry of Petroleum & Natural Gas, 2023). Across the entire road transport subsector, biofuels are forecast to not exceed 3% of total energy consumption, peaking at 330 PJ in 2043.

Green hydrogen and ammonia

Hydrogen can be combusted or used in fuel cell batteries but can also be converted into green ammonia and synthetic e-fuels. Ammonia has long been valued as a fertilizer but can also be sold as low-carbon fuel for maritime transport. Green ammonia exports are ramping up, such as the Indian firm AM Green signing production agreements with Norwegian firm Yara Clean Ammonia (Atchison, 2024). Moreover, manufactured goods using green hydrogen can be exported globally as a low-carbon product, such as iron and steel. We forecast the subcontinent to supply up to 36 Mt/yr of ammonia by 2050, with a slight decline to 30 Mt in 2060.

India aims to expand its hydrogen capacity through the National Green Hydrogen Mission, where the objective is to incentivize the production of 5 Mt of green hydrogen and the manufacturing of 60–100 GW of electrolyser capacity by 2030 (MNRE, 2023b). Reflecting a strategic pivot from exports to domestic consumption, the Solar Energy Corporation of India (SECI) withdrew its tender for green hydrogen hubs. However, SECI is catalyzing the domestic ecosystem by awarding 900,000 t/yr of green hydrogen production capacity and facilitating the procurement of 350,000 t/yr of green ammonia with additional capacity expected to be floated. Pakistan is also exploring hydrogen electrolysis pilots harnessing the Ghazi Barotha Dam and Quaid-e-Azam Solar Park (Engineering Review, 2024). We forecast that the Indian Subcontinent will achieve 8.6 Mt of hydrogen production by 2030 and 18 Mt in 2060.

Nuclear

Various countries are setting targets for nuclear power capacities. India, as part of its Viksit Bharat goals, is targeting 100 GW of nuclear power by 2047, with an interim goal of 22 GW by 2032. Pakistan also has a 2050 goal of 40 GW, with a 2030 interim milestone of 8.8 GW (Jaspal, 2025). While Bangladesh does not current have nuclear capacity, the Rooppur plant is under construction, and the country ultimately targets 7.2 GW capacity by 2041. We forecast a gradual buildup of capacity in the region, with 25 GW by 2030, and 58 GW in 2060. These projections are below the stated targets in the region, nuclear is expected to be an important non-fossil baseload power supply to the grid.

Small modular reactors (SMRs) are being assessed as a possible alternative to utility-scale nuclear plants. With their relatively small physical footprint and customizability, SMRs could potentially be deployed faster and displace localized industrial generators. Countries in the region have considered and published preliminary findings on the potential for SMRs (Niti Ayog, 2023; IAEA, 2024).

Fossil fuels

Coal continues to be the main energy supply in India, abundantly available to extract domestically. Other countries in the subcontinent, like Pakistan and Bangladesh, are more dependent on fossil fuel imports, although India also imports up to 36% of its total energy supply (IEA, 2025). While manufacturing and power sectors are projected to enter peak coal in the 2030s before declining, oil and natural gas will remain significant parts of the primary energy supply mix.

Coal – legacy economic driver for India

With India having the fifth-largest coal reserves globally and being the second-largest consumer, coal remains a critical energy source for the country, which currently produces 930 Mt of it annually. Due to the dominance of India’s economy in the subcontinent, coal is by extension a major energy supply for the region at 23,000 PJ/yr, or 40% of the regional supply mix. Electricity generation is similarly reliant on coal supply, which currently fuels 1,500 TWh/yr (65%) of generation. India continues to have coal plant construction in the pipeline into 2030 as the nation grapples with the dual challenge of achieving 50% non-fossil power in 2030 but also modernizing into a USD 30trn economy by 2047 (NITI Ayog, 2025a).

Coal is currently the primary energy source in both power and manufacturing. As these sectors increase the uptake of electrification and non-fossil alternatives, regional coal demand will peak in the 2030s and begin to decline within the decade. However, since the coal industry is a major part of the Indian economy, coal production will not decline immediately in the region but will peak in 2040 at 1,400 Mt/yr and will decline to less than 500 Mt in 2060.

Oil and gas

The Indian Subcontinent is highly dependent on imports for its oil supply: it produces just 0.7 Mbpd of the 5.4 Mbpd of the oil it consumes today. India is exploring offshore drilling and has recently discovered a large source of hydrocarbon supply, up to 371 Mtoe, in the Andaman Sea (Ministry of Petroleum & Gas, 2025). This discovery alone, if fully realized, would be equivalent to several years of domestic oil consumption. Although we forecast peak oil consumption in 2040 at 8 Mbpd, oil supply is expected to remain significant in the primary supply mix into 2060 and beyond.

Natural gas has a very different profile in the region compared to coal. India is predominantly reliant on gas imports in liquid form (LNG), while countries like Bangladesh and Pakistan have largely self-sufficient supplies. However, IEA production reports indicate that both counties may have hit a production peak and plateau, with a possible decline looming (2025b,d). Our forecast shows that production will be largely stable at 100 Bcm and the supply-demand gap will continue to widen thought to 2060. To accommodate the continued increase in supply needs, India is expanding its gas pipeline infrastructure from 25,000 km to 33,000 km. The TAPI (Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India) gas pipeline under development is expected to deliver an additional 33 Bcm to the region (Indeo, 2025). The pipeline is a sign of the continued and growing reliance on natural gas in the subcontinent.

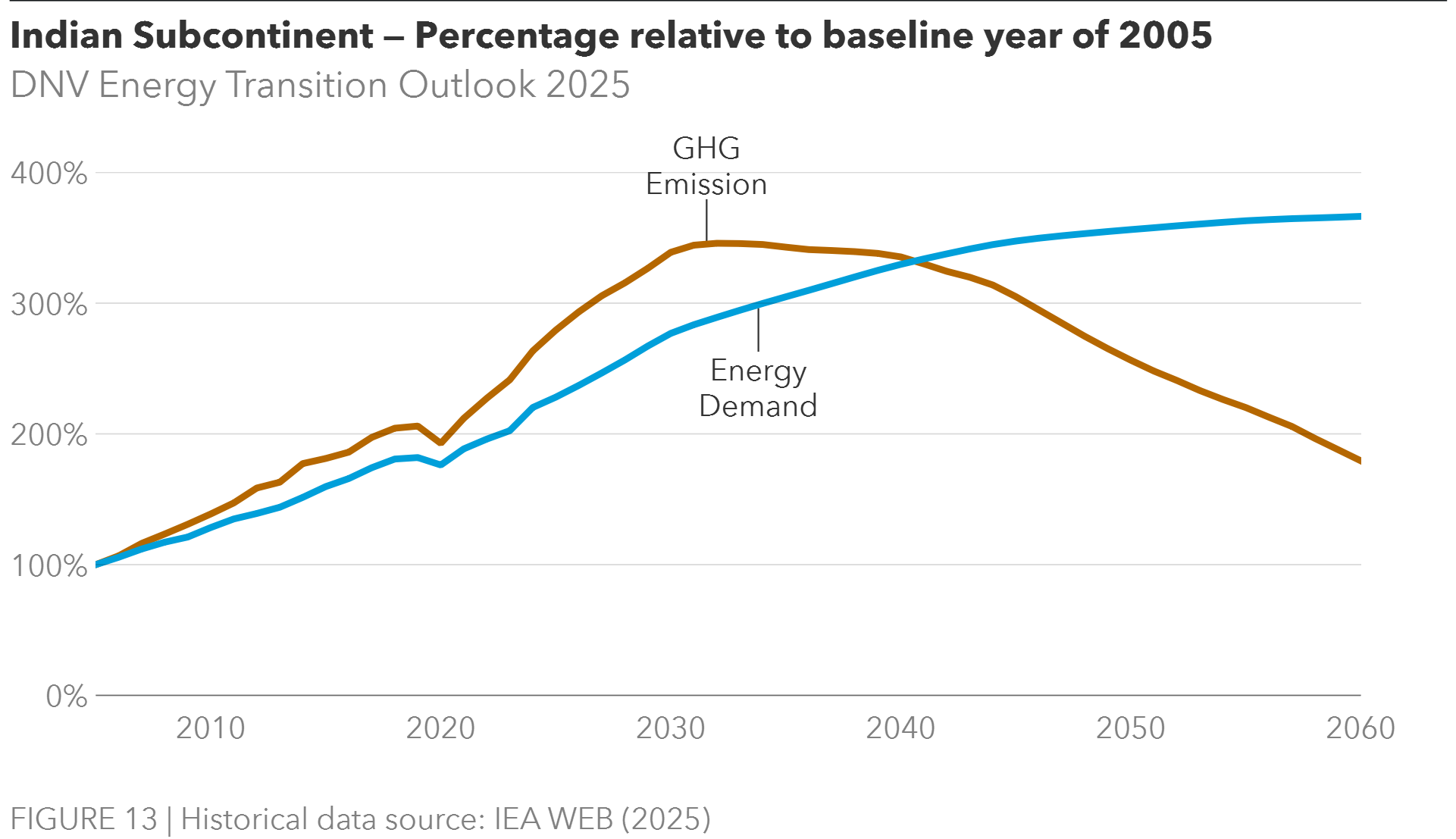

GHG emissions and the future for carbon capture and storage

Countries in the region have set their own emission reduction targets in their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC). India, for example, have an emission intensity (CO2 per GDP) reduction target of 45% by 2030, compared with 2005. In this context, our forecast (considering energy and industrial process-related CO2 emissions) suggests a reduction of 22% in carbon intensity of the economy by 2030 for the Indian Subcontinent. Other countries, such as Pakistan, have instead called for 50% emission reduction by 2030 compared to a business-as-usual emission projection. The Indian Subcontinent's country NDC pledges aim to limit growth in emissions to no more than 333% by 2030, relative to 1990. The ETO indicates energy- and process-related CO2 emissions – after carbon capture and storage (CCS) and direct air capture (DAC) – increasing by 605% over this period. Our ETO forecast ends in 2060, and between 2024 and 2060, the region decreases energy- and process-related CO2 emissions after CCS and DAC by 33%. The emissions peaking in the early 2030s is followed by a decreasing trend, which is promising for net-zero emission trajectories such as India’s goal to be carbon-neutral by 2070.

We project a continual increase in regional energy demand until 2060; however, the forecast shows a decoupling of carbon emissions. Regional emissions peak in the 2030s at 4.8 GtCO2/yr, then decline to 2.5 GtCO2/yr, near 2015 levels. This reduction is attributed largely to the forecast peak coal usage in manufacturing and power in 2031 and the steady reduction thereafter. Then, road transport continues this trend in the 2040s, when peak oil occurs in 2041, owing to transition to EVs.

Carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) is generating considerable interest, especially among hard-to-abate sectors such as cement manufacturing. We forecast that the main sectors where CCUS will occur are manufacturing, power and hydrogen production, and maritime transportation. There are very low capture capacities in 2030, but by 2060 there will be a regional ramp up to 94 Mt of carbon capture annually, or 4% of total emissions. NITI Aayog concludes that for India, carbon capture will be an ‘indispensable’ solution in meeting emission targets for industries such as cement (Niti Aayog, 2025b). With the country’s planned transition to an emissions trading system (ETS) from the current Perform, Achieve, and Trade (PAT) programme, CCUS would become an increasingly economically viable option.

Policy summary

A non-exhaustive list of sector policy initiatives, emphasizing the 2024 to 2025 period

|

Climate targets - Key countries India: net-zero by 2070. Pakistan aims to reduce GHG emissions by 50% by 2030 with 35% conditional on international support |

||

|

Sector |

Policy details and example initiatives |

Mechanism(s) |

|

Power |

> India uses competitive bidding for utility-scale renewables, offering 25-year PPAs via SECI. It plans 50 GW annual capacity additions through 2027-2028, including 37 GW offshore wind by 2030, and aims for 500GW by 2030. > Bangladesh targets 20% renewable generation by 2030, and 30% by 2040. The Renewable Power Policy 2025 promotes rooftop solar with net metering, renewable portfolio obligations (RPOs) on utilities and designated consumers and renewable certificates. Projects benefit from 10-year corporate tax exemptions. Land constraints limit utility-scale growth, but Solar Home System supports off-grid access. > Pakistan aims for 60% renewables by 2030. Net metering regulations offer high buyback rates and long-term licenses, boosting rooftop solar. The China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) of the Belt and Road initiative has shifted to renewables since 2023. |

Targets Tenders / auctions

Mandates Tailored loans, microfinance Market design

International finance

|

|

> Energy storage includes India advancing battery- or pumped storage projects through technology agnostic tenders. 0.5MW storage is required per MW solar PV. The renewable purchase obligation (RPO) on distribution companies includes a gradually increasing storage mandate reaching 4% (as % of renewable plant capacity) by 2029–2030. A rise to 10% is under consideration. |

Tenders/auction Mandates |

|

|

> Coal additions are planned to continue, such as India targeting 80 GW new coal additions by 2031/32. India, Pakistan and Bangladesh have 120 GW, 2 GW and 7.5 GW, respectively, in pre-construction and construction phases according to Global Coal Plant Tracker (July, 2025). |

Plan Limited carbon pricing |

|

|

> Nuclear expansion is planned, including India to triple the installed capacity (over 7 GW to around 22 GW by 2031/32, and 100GW by 2047). Designs for industrial captive power and decarbonization are promoted in public-private partnerships. International collaboration on modular reactors. Pakistan has plans to expand capacity, cooperating with China. |

Public budgets, R&D Public-private partnerships Cooperation, international partnerships |

|

|

Grids |

> India’s Central Electricity Authority plans substantial additions to the HVDC infrastructure to further connectivity between regional power grids. > Several region countries have extensive engagement with China’s Belt and Road initiative, Pakistan is a large receiver of investments in energy infrastructure. |

International partners |

|

Hydrogen |

> India’s Hydrogen Mission targets 5 Mt renewable hydrogen annually by 2030, requiring 125 GW of renewables and 15 GW of electrolysis, driven by incentives for production, infrastructure development and market expansion. SIGHT programme bidders in the second renewable hydrogen auction were announced January 2025, allocating subsidies that decrease over a three-year period. |

Tenders/auctions Government funding

|

|

CCS/DAC |

> India leads the region’s steps to advance CCS, guided by NITI Aayog’ policy work (2022). No official capture target exists. The government plans to launch ‘Mission CCS’ to build a domestic ecosystem, drawing on experience from other schemes to support capital costs. See DNVs Energy Transition Outlook: CCS to 2050 for further details. |

Government funding |

|

Transport |

> India has a long-standing Ethanol Blending Programme, aiming for 20% ethanol in gasoline by 2025/2026 (at 18% at the end of 2024). In electromobility, India targets 30% of new vehicle sales by 2030 supported by FAME II purchase incentives. Public procurement intends to aggregate demand to EVs in the national vehicle fleet. > Pakistan’s Accelerated Vehicle Electrification (PAVE) Scheme emphasize two-wheelers and three-wheelers. |

Blending mandates Government funding Public procurement |

|

Manufacturing |

> Regional support for industrial decarbonization is limited. India emphasizes fuel-switching via Renewable Purchase Obligations (RPOs) and energy efficiency through the PAT scheme. Hydrogen use mandates are under consideration, supported by Viability Gap Funding to offset clean tech costs. Policies are emerging for a distributed H2 model with electrolysers/ renewables co-located with industry and for CCS deployment. India’s carbon credit trading scheme will cover 16% of emissions in the energy-intensive industrial sectors will commence during 2026. |

Efficiency and RE mandates Government funding Tenders/auctions (H2, RE PPAs) Limited carbon pricing |

|

Buildings |

> The 2022 amendment to India’s Energy Conservation Act empowered the Bureau of Energy Efficiency to enforce the residential building code (Eco-Niwas Samhita) with minimum energy standards. National programmes include UJALA (LED lighting), clean cooking, AC replacement, and PM Surya Ghar (solar rooftop subsidies up to 60%). > Regional efficiency efforts face challenges from low electricity tariffs and fossil-fuel subsidies, which weaken incentives for investment and technology shifts. |

Standards Fossil-fuel subsidies |

References

AngelOne (2025). India Cuts Solar Imports: Dependence on China Drops to 56% for Cells, 65% for Modules: Report.

Atchison, J. (2024). Yara Clean Ammonia and Greenko: renewable ammonia term sheet signed.

CEEW - Council On Energy, Environment and Water (2025). What is Fuelling India’s Road Transport Sector?

Chambers & Partners (2025). Renewable Energy 2025 Bangladesh. September 25.

EconomyNext (2023) Sri Lanka sets ambitious climate targets for 2042, 2050

Engineering Review (2025). Hydrogen Strategy 2025: Recommendations for Pakistan.

ENN - Emergency Nutrition Network (2024) Scaling up clean cooking in India: What this means for nutrition, health, and beyond.

German Watch (2025). Climate Risk Index 2025.

IAEA - International Atomic Energy Agency (2024) 22nd INPRO Dialogue Forum on Successful Development and Sustainable Deployment of SMRs.

IEA – International Energy Agency (2025a). Fossil fuel subsidies. Accessed August 25. 2025.

IEA -International Energy Agency (2025b) Bangladesh - Countries & Regions - IEA.

IEA - International Energy Agency (2025c) India - Countries & Regions - IEA.

IEA - International Energy Agency (2025d) Pakistan - Countries & Regions - IEA.

Indeo, F. (2025) TAPI Gas Pipeline: A Paradigm of the Central Asian Pragmatic Approach Toward Taliban. TRENDS Research & Advisory.

Jaspal, Z.N. (2025) Pakistan’s pursuit of nuclear energy is essential to its future – MEPEI. Middle East Political and Economic Institute (MEPEI).

Ministry of Petroleum & Natural Gas (2025a) Andaman Oil Exploration.

Ministry of Petroleum & Natural Gas (2025b) India’s Ethanol Journey is Unstoppable: Shri Hardeep Singh Puri. Ministry of Petroleum & Natural Gas.

MNRE – Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (2025a). India’s RE Capacity Registers 15.84% Year-on-Year Growth.

MNRE - Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (2025b) India’s Renewable Energy Capacity Achieves Historic Growth in FY 2024-25.

MNRE - Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (2025c) India’s Renewable Rise: Non-Fossil Sources Now Power Half the Nation’s Grid.

MNRE - Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (2025d). Energy Storage Systems(ESS) Overview.

MNRE - Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (2025e). India’s Renewable Energy Revolution.

MNRE - Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (2025f). PM Surya Ghar: India’s Solar Revolution.

MNRE - Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (2023a) Intra-State GEC Phase-I.

MNRE - Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (2023b) National Green Hydrogen Mission.

National Portal of India (2025) PM Surya Ghar - Muft Bijli Yojana.

NITI Aayog (2025a). Coal Power Sources in India.

NITI Aayog. (2025b). Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage (CCUS) in Indian Cement Sector. Workshop on CCUS in Indian Cement Sector.

NITI Aayog. (2023). The Role of Small Modular Reactors in the Energy Transition.

Renewables First. (2023). Pakistan Renewable Energy Potential.

Renewables First (2025). Leader of One or Leader of None - China’s choice for clean over coal in Pakistan

United Nations (2025) World Population Prospects.

World Economic Forum (2025) Pakistan’s energy transition via solar power and batteries.

World Economic Forum (2024). Unlocking Private Sector Investment into Natural Climate Solutions in India.

World Bank. (2025). Global Economic Prospects.

Yousafzai, F. (2025) Battery Energy Storage Systems can transform power sector amid renewable energy surge: Experts.