Asun Lera St.Clair1.2 , Eelco Kruizinga1, Jorge Paz3.5 , Marina Baldissera Pacchetti4.2, Saioa Zorita Castresana2 and CarolLiffman1

DISCLAIMER: Statements in this article represent views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the positions of DNV or any other partners.

Climate Week NYC, a week of events convening a very diverse set of change makers and climate champions from industry, politics and civil society, ended with restated wishes for the world to drive and speed up transformation to a resilient future. The 2023 edition of the Climate Week NYC was set against the backdrop of unprecedented climate extremes across the planet taking lives and affecting critical infrastructure, energy security and health, assets, business continuity, markets and investments. The motto ‘we can, we will’ aims to convey that we are still on time to ride this transformation of the global climate system in a fair and just manner. This is still the sentiment we see in the lead-up to COP28, being very much focused on ‘delivering’ on climate change goals.

The core message is twofold: change makers must act swiftly to prevent more climate-change-related disruptions through decarbonisation strategies and net-zero pathways, while at the same time crafting adaptation plans to ensure resilience to unavoidable risks. This needs to happen against shifting insights: as science demonstrates, the warming of the planet impacts regional and local climates whereas climate variability is also increasing. All these changes must be properly understood and appropriately integrated in decision-making. In this short article, we focus precisely on this topic: the central role that trustworthy and relevant climate information has for both decarbonisation and risk management.

The foundational role of climate services for business organisations

Many say it is not possible to be in business without being a risk-taker. However, too much uncertainty will disrupt operations, kill projects, and ultimately threaten business survival. According to the World Economic Forum, climate change is related to both short- and long-term risks, introducing many uncertainties across the links in value chains and across multiple time horizons. Businesses need help understanding the magnitude of that uncertainty. Climate information – that is, the data, knowledge, models, predictions, and forecasts that enable us to understand past, current, and future climate and estimate climate variability – plays a foundational role in achieving a green transition, climate neutrality, and climate resilience. This role can materialise only if trustworthy climate information is appropriately delivered and effectively used, integrating weather and climate information with other decision-making elements to better manage risks and realise opportunities. This merging of diverse types of data driven by the overarching goal of informing decision-making, suited to specific stakeholders’ contexts, is what defines climate services.

Climate services are receiving increased attention, and there are a large variety of initiatives engaged in their provision, both in the public and the private sector, creating a fairly new domain in both research and in the market. Climate services are critically relevant for businesses, given that most organisations are crafting decarbonisation pathways, evaluating their exposure to physical and transitional climate risks, and often need to disclose these against widely recognised guidelines such as those of the Task Force for Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), the EU Taxonomy, or in response to investors’ demands for sustainable finance.

A growing market in need of governance

A growing climate services market includes for-profit and not-for-profit actors that play a role in the development and provision of climate services, creating an arena where supply and demand meet and interact to advance climate-aware decision-making processes and create new opportunities emerging from improved risk assessments. Although the scientific basis of climate services has seen a spectacular improvement in the past years and has become increasingly sophisticated – partly driven by the deployment of digital technologies, infrastructures for high-performance computing, more sophisticated weather models, the increased deployment of AI to fine-tune models, the ability to handle very large amounts of data, and public research investments – there is evidence that many of the existing climate services in the market are of unequal quality.

At the same time, the demand is increasing. Sophisticated modelling of physical risk has moved from being a nice-to-have to an essential requirement. Many service providers can now determine a score or risk-exposure profile for different hazards in a given climate scenario. It is essential to know how such scores are calculated as well as the bandwidth of the uncertainty that underpins the calculation, because the stakes can be very high: the wrong decision can lead to costly damage. Thus, transparency of the various components of the climate service used – such as the quality of data and data processing, bias correction techniques, uncertainty quantification, downscaling and combination of multiple data sources) – is essential to assess the boundaries of application of the climate service.

However, incorporating the latest scientific insights into a business decision requires something else. Climate-related decision-making needs integration of model-based information with contextual and domain-related information into corporate risk management. This in turn requires adaptation of governance processes for risk decision-making. These processes are in fact as fundamental as high-quality data or suitable timeframes, as it is evident that the extent of climate services influences decisions regarding other types of risks. Climate change is not a risk that occurs in isolation. For any type of business, there may be interconnections between climate and other significant sources of risk affecting the business, which could even entail cascading risks.

Thus, a more mature governance system for the development and use of climate services is urgently needed. Despite the increasing scientific evidence and demand for climate services, widely acknowledged standards, guidelines and good practices are lagging behind, resulting in climate services of uneven quality and usability. But the task is more complex than maturing a set of technical standards or improving research. The utility of climate services is determined by the level of user engagement, co-design, and co-production employed during their development; in fact, state-of-the-art research shows that co-production of these services together with users is necessary to provide efficient and effective services that bring together supply and demand. That is, the governance of climate services requires a broad consensus across a wide variety of stakeholders, representing a mix of technical, socio-economic, and domain knowledge within all relevant industries.

Climateurope2: Support and standardisation to enhance trust in climate services

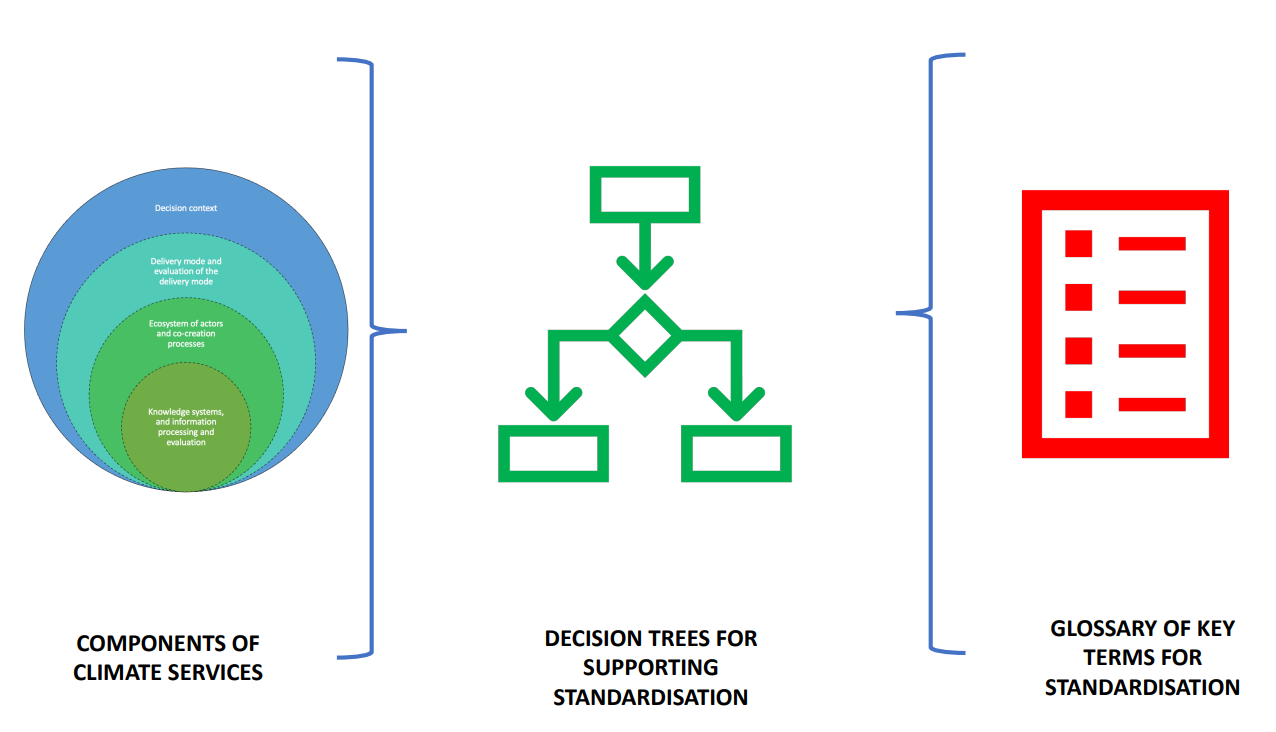

Climateurope2 is the first coordinated effort at the European level to identify the potential and the maturity of the different components of climate services for standardisation. It is part of the European Commission’s efforts to implement the Green Deal and the widely supported mission of a resilient Europe. The project aims to develop the quality basis for future equitable and quality-assured climate services to all sectors of society by developing standardisation procedures for climate services, supporting an equitable European climate services community and enhancing the uptake of quality-assured climate services, to ultimately support mitigation of and adaptation to climate change and variability.

Coordinated by the Barcelona Supercomputing Center (BSC) Earth Sciences Department along with 32 partners including the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and Copernicus, the European Union flagship programme on Earth observations, Climateurope2 identifies standardisation needs of climate services, including criteria for certification and labelling, as well as user-driven criteria needed to support climate action. This information will be used to propose a taxonomy of climate services, suggest community-based good practices and guidelines, and make recommendations for standards development where possible.

A framework to support equitable standardisation of climate services

The project has already produced an initial document that highlights a potential strategy for the standardisation of climate services with the goal of enhancing the trust and legitimacy of available services and guide the development of new ones, given that standards act as guideposts to establish a common understanding among parties that enter into a legal voluntary or social engagement.

There are standards for just about everything: for assuring the safety of products, protecting and restoring the environment, ensuring the wellbeing of people, regulating finance or supply chain flows, building technical infrastructure, ensuring corporate responsibility, or for measuring greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The vast majority of standards are voluntary norms rather than enforceable laws. Still, their widespread use makes standards difficult to avoid because they form an integral part of the governance of technology in society. If we want to effectively guide climate action, standards must become part of the toolbox at our disposal for enhancing the development, implementation, and evaluation of climate services. However, the complexity of the different elements of climate services, combined with the fact that standardisation is a thorough multinational, multistakeholder consensus process aimed at building uniformity, interoperability, and benchmarks, makes the task far from trivial.

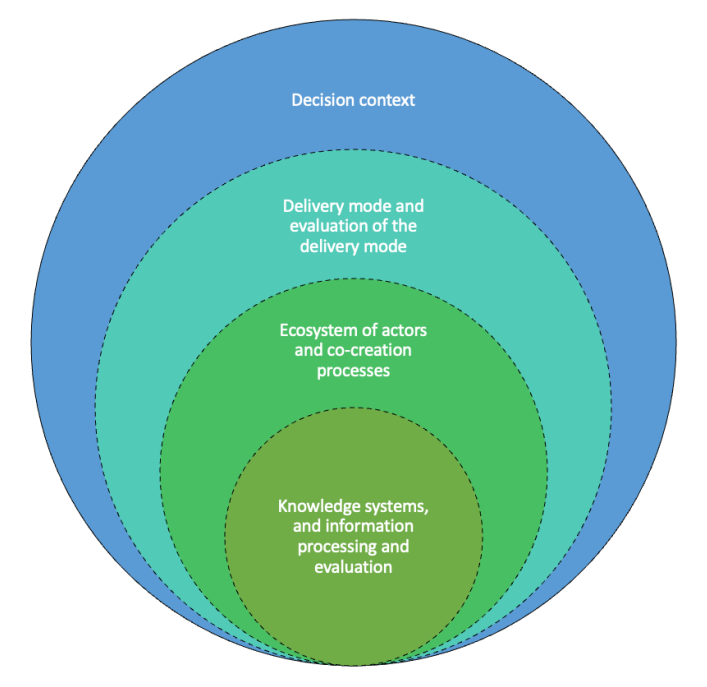

In a coordinated effort across all partners in the project, DNV Group Research and Development alongside TECNALIA and the BSC have produced a first draft of a Framework for the equitable standardisation of climate services. To facilitate our work, it is useful to divide climate services into different components. These components are just an attempt to provide some boundaries and at the same time break the complexity of climate services into recognisable sets of data, processes, products, and actors. The components of climate services are described as follows:

• The decision context: The decision context refers to the kinds of decisions the climate services support, including geographical and political context. This in turn includes the policy structure and other forms of governance that require and enable the development of climate services.

• Knowledge systems of different types (quantitative, qualitative, mixed data; local knowledge; etc.) and related selection, evaluation, and translation processes: This component relates to climate data, among other things. Environmental, social, economic and technical, as well as engineering data and local knowledge to develop and implement local adaptation and mitigation strategies, are also relevant. As are all selection, evaluation, and translation processes related to this data. Data accessibility, storage, and stewardship would also fall under this component.

• Delivery mode and evaluation of the delivery mode: This component regards how a climate service is delivered, and how this delivery is evaluated at various steps. This should include the tailored aggregation and combination of data and processes to match the decision and context of the service client.

• Ecosystem of actors and co-creation processes: This component identifies the different actors involved in (co-)producing, evaluating, and taking up climate services, as well as the actors that might become relevant because of a particular decision context (see Component 1). This component also addresses the co-production processes that are relevant for different actors and different stages of the climate service development process. Each of these components can help navigate the complex territory that forms the boundaries of climate services, as a means to help create consensus and guide the strategy of the eventual formal standardisation of climate services.

Ensuring the quality of climate services for industry

The importance of this disaggregated understanding of climate services was illustrated during a recent virtual festival: the Climateurope2 second Webstival. In a set of debates between policy makers, business leaders, and the climate services research community, we had the opportunity to dialogue with several business and research leaders working on the challenges ahead for the provision of climate services for businesses and in particular for the renewable energy sector. We heard from actual users about how critically important appropriately delivered, high-quality climate data are for customers, and how this is reinforced by a large number of disclosure frameworks such as the Task Force of Climate Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) and myriad other regulations (up to 35 countries will implement disclosure regulations by 2025). The discussion highlighted that, in general terms, energy companies have included climate risks in their environmental, social, and governance (ESG) practices and reporting as well as for strategic planning.

During the opening of the Webstival Business Day, we heard an inspiring presentation by Ditlev Engel, CEO of DNV Energy Systems, who emphasised that the energy transition hinges on the scaling-up of renewables.  Engels also presented highlights from the recently published Energy Transition Outlook for North America and noted the critical importance of considering climate risk for energy security and an effective transition. Although a technological and economic perspective is key, the bulk of the response is in the hands of governance actors, including private governance actors working on standardisation, verification, and certification.

Engels also presented highlights from the recently published Energy Transition Outlook for North America and noted the critical importance of considering climate risk for energy security and an effective transition. Although a technological and economic perspective is key, the bulk of the response is in the hands of governance actors, including private governance actors working on standardisation, verification, and certification.

In a follow-up panel discussion, this importance of governance systems was reasserted by Carlo Buontempo, Director of Copernicus Climate Service, who stressed the importance of standardisation to enable comparable, high-quality climate services. ‘Quality assurance for climate services is key,’ noted Francisco Doblas Reyes, Director of the Barcelona Supercomputing Center Earth Sciences Department, ‘because we may be facing a near future where liability may come into play if companies do not use the right climate information to disclose risk exposure. We see already insurance companies working on such kind of verification,’ he pointed out.

As mentioned, a major driver for enhancing the quality of climate information for decision-making through standardisation and certification mechanisms is that many companies must report compliance with regulations and guidelines demanded by the finance sector. Sophie Rathmes, Science Officer for Sustainable Finance at the European Commission (EC), provided an overview of the various policy instruments that the EC is rolling out to support the green transition and indicated the importance of reliable climate information in order to support trustworthy disclosure of climate impact on current assets and future investments. This topic was also explored in a follow-up session.

Another follow-up session dived into the standardisation and quality assurance of climate services for the energy sector. The role of climate services for the energy sector has been explored in depth by the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) State of Climate Services 2022 Report. Hamid Bastiani, Policy Officer for WMO, explained that the report describes how improved weather, water, and climate services can be used to increase the resilience of the energy sector to climate-related shocks and inform measures to increase energy efficiency across multiple sectors. It also illustrates different initiatives to improve energy infrastructure resilience and security through better climate services, supported by sustainable investments.

Climate services are also key for net-zero strategies. The recent report from WMO on Integrated Weather and Climate Services in Support of Net Zero Energy Transition (WMO-No. 1312) provides background and guidelines to strengthen the development, and enable a widespread uptake, of integrated weather and climate services for this sector. This document maps different time scales of climate data suitable for decisions in the energy sector, from weather forecasts for enhanced operation and management of energy operations, to climate projections for planning and investment decisions. It was also noted that Artificial Intelligence (AI) and other scientific advances, e.g. in weather forecasting, are key drivers for the development of climate services and will influence the market. But enhancing quality requires a deeper understanding of users across the diverse components of climate services. This involves collaboratively producing and analysing user requirements to develop and update climate services successfully.

A deep dive into business perspectives on climate services and energy systems

During a panel with business representatives, we repeatedly heard about the importance that climate services have for appropriate and effective identification and management of risks, uncertainty, and opportunities. Carol Liffman, Director of Risk Advisory Services in DNV Energy Systems, highlighted key customer needs and presented a comprehensive overview of climate data usage from the users' perspective as well as the importance of managing risks and uncertainty through quality-assured systems.

Nevertheless, companies’ priorities in relation to climate change are remarkably diverse and depend on the type of organisation (e.g. company size) and its position in the energy value chain. She presented a summary of how different agents in the energy sector are working to incorporate climate services in different activities and decisions considering different timescales and objectives. For example, oil and gas companies, although still focusing primarily on mitigation of greenhouse gases (GHG), are paying increasing attention to the water-energy nexus, incorporating adaptation approaches into their operations. In the case of renewables, the use of short-term meteorological services in operation and management is the current practice, but the sector is incorporating gradually longer-term climate information, paying special attention to extreme events. Utility companies are also interested in extremes and their impacts but are usually more interested in the long-term planning of their assets and strategies. Large energy companies are beginning to rethink planning in view of the information provided by climate services. Climate services are also used to face insurance challenges and understand the magnitude and frequency of catastrophic events, as well as their consequences and potential changes.

Nevertheless, companies’ priorities in relation to climate change are remarkably diverse and depend on the type of organisation (e.g. company size) and its position in the energy value chain. She presented a summary of how different agents in the energy sector are working to incorporate climate services in different activities and decisions considering different timescales and objectives. For example, oil and gas companies, although still focusing primarily on mitigation of greenhouse gases (GHG), are paying increasing attention to the water-energy nexus, incorporating adaptation approaches into their operations. In the case of renewables, the use of short-term meteorological services in operation and management is the current practice, but the sector is incorporating gradually longer-term climate information, paying special attention to extreme events. Utility companies are also interested in extremes and their impacts but are usually more interested in the long-term planning of their assets and strategies. Large energy companies are beginning to rethink planning in view of the information provided by climate services. Climate services are also used to face insurance challenges and understand the magnitude and frequency of catastrophic events, as well as their consequences and potential changes.

As a result of this demand, sophisticated risk management tools and platforms have become a reality in last few years. Different providers have created an interesting and active market of solutions that allow companies to evaluate risks associated with their assets. However, the high interrelation between all the components of the energy networks confers a special importance to cascading and compound risks in the sector. The capacity of the existing tools to evaluate these risks in a highly interconnected network is still an approach that may be improved.

But data is just the start; turning data into viable business actions requires something more, namely good decisions. Making a great decision every time rests on candid dialogue – or what some would call ‘talk therapy’ – among stakeholders using a proven process. By using a structured decision-making process, which we sometimes refer to as decision quality, we maintain alignment, uncover hidden biases and issues, and focus on the end goal of commitment to action.

Maria Ubierna, Open Hydro Chief Product Officer (CPO), elaborated on how hydropower is one of the main technologies to reduce GHG emissions, even though not all operations are sustainable. At the same time, hydropower is very vulnerable to climate change as it depends on water resources. At a global level, it is necessary to double hydroelectric capacity to achieve GHG reduction objectives. Combined with an ageing park and other trends, such as the growing interest for reversible plants, this points towards important projects and investment flows in the next decades, creating a context that can facilitate the sector’s uptake of climate services.

Regarding the evolution of the use of climate information for decision-making, Ubierna explained that a change in hydropower practices took place around 2015, when climate change projections started to become frequently employed. This was accompanied by a change in certain methods and calculations, moving from a deterministic to a probabilistic approach, which indicated an increasing demand for transparency in the generation of climate data.

Another change in the hydropower sector was that the incorporation of climate change stress tests in project developments became a demand, and the International Hydropower Association (IHA) assumed the preparation of a guiding document: the IHA guidelines, which were launched in 2019 in response to the need for clarity in good international industry practice when considering climate risks. The Guidelines offer a methodology for identifying, assessing, and managing climate risks to enhance the resilience of hydropower projects and include different approaches for different levels of risks and data availability, allowing a flexible application depending on the context. This methodology tries to find a compromise between climate services research excellence and industry practice timelines to deliver a robust risk assessment. Standardisation of climate services can be vital for that compromise in that they shorten timeframes while ensuring quality.In addition to the aforementioned reporting frameworks, Ubierna highlighted the importance of the EU taxonomy for sustainable activities as a driver for enhancing the incorporation of climate services in the hydroelectric sector. This initiative establishes that, to consider a hydroelectric plant as ‘sustainable’, it must incorporate aspects of both adaptation (climate risk analysis) and mitigation. This intervention concluded with recommendations to advance the uptake of climate services and their standardisation. A common language spoken by all actors engaged in the energy value chain is key, as well as strengthening collaborations between climate services research projects and companies to ensure industry uptake.

Albert Soret, Team Leader of the Barcelona Supercomputing Center Earth Services Section and leader of a European project exploring climate services for renewables (S2S4E), discussed with Daniel Cabezon, Team Leader at Energeias de Portugal Renewables (EDPR), the challenges and benefits of active partnership with industry specialists. This exchange illustrated that there is a significant effort required to translate climate information into a service, that is, into something useful and practical for decision-making. The role of staff inside a company able to translate climate information to other colleagues and departments is particularly important. An appropriate understanding of climate variability and future climate change to inform the whole project cycle, from identification of sites to development and operations to economic assessments, is a necessary condition along with the ability to evaluate the quality of models and their applicability in various locations and scales. The partnership with the S2S4E project enabled EDRP to mature novel decision-support tools developed based on the project’s predictions, tailored to users’ needs and following a user-centred approach.

Concluding Remarks

To conclude, the quality assurance of climate services is critical for a sustainable and resilient future for all actors in society. Businesses are becoming more and more aware of the need to incorporate medium- and longer-term climate information along with short-term weather and climate variability information into their decision-making processes and risk management strategies. Given the stakes involved, there is a need to increase the quality and usability of climate services, while at the same time addressing efficiency and short-term needs. As climate services can represent a complex combination of information, products, processes, and actors, the quality and usability are determined by the quality and capability of each component part. Decision-making processes on climate-related impacts need to be based on appropriate stakeholder engagement, dialogue and co-production. As the number of providers of climate services is growing and the sophistication of their tools and models is enhanced through the use of novel digital technologies like AI, there is an urgent need to govern this market through the development of guidelines, recommended practices and standards covering all the components of climate services.

1DNV

2 BSC

3TECNALIA

4University College London (UCL)

5Comillas Pontifical University