|

|

2024 |

2060 |

|

Population |

702 Million |

801 Million |

|

GDP* |

USD 11.6 Trillion |

USD 27.6 Trillion |

|

GDP/person |

USD 16 400 |

USD 34 500 |

|

Energy use |

EJ 35 |

EJ 52 |

|

Energy use/person |

GJ 50 |

GJ 65 |

|

Energy-related CO2 emissions |

Gt 1.9 |

Gt 1.2 |

|

Energy-related CO2 emissions/person |

2.7 tonnes |

1.4 tonnes |

This region stretches from Myanmar to Papua New Guinea and includes the Pacific Island States.

Point of reference

Current situation

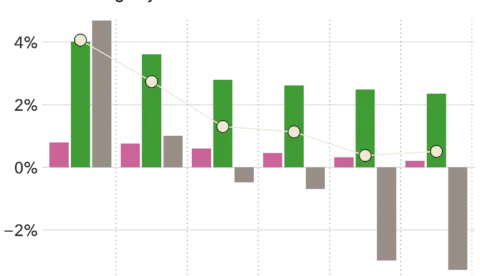

- GDP has grown 46% over the decade (2014-2024) and together with growth in populations and achieving access to electricity in nearly all countries, electricity demand has risen sharply, most recently 5% annually on average between 2020-2024.

- Fossil fuels have a stronghold in energy and electricity mixes, accounting for around 80% of primary energy and 72% of generation in 2024. Coal and natural gas from Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand play dominant roles, while the region is heavily import reliant for its oil use.

- Renewables have gained momentum supported by policy reforms and private investments. Capacity increased 30% between 2020 and 2024 – from 104 GW to 136 GW. Renewable energy-related industries attracted on average over USD 27 billion annually during 2020-2023, equivalent to a quarter of greenfield investments in the ASEAN region (ASEAN, 2025).

- Climate risks include sea-level rise, extreme storms and storms, floods and rising temperature. Over the period 1993-2018, ASEAN countries experienced direct economic losses of USD 124 billion from weather-related events (Met Office, 2024).

Fossil Energy

have a stronghold in energy and electricity mixes

GDP Growth

GDP has grown 46% over the decade (2014-2024)

In Greenfield

Renewables have gained momentum supported by policy reforms and private investments.

Billion losses

Rectangle 8, TextboxClClimate risks include sea-level rise, extreme storms and storms, floods and rising temperature.

Pointers to the future

- South East Asia attracts manufacturing relocations and ‘China-plus’ supply-chain strategies and is an offshore manufacturing base for Chinese companies, notably in cleantech, including through the Belt and Road Initiative. At the same time, rising imports from China – driven by industrial overcapacity – pressure economies, as low-priced goods spill into the region (Kelly et al., 2025).

- Soaring electricity demand driven by a growing middle class, industrial activity, urbanization and digital economy expansion, have governments balancing energy security, affordability and sustainability through mixed energy technology strategies.

- Policies promote biofuel-blending into transport fuels. Renewable electricity deployment is accelerating through grid interconnection, BESS integration, and diversified RE auctions. Still, further regional coordination and clearer regulations are needed to fully unlock decarbonization potential and improve energy security.

- Coal remains entrenched in South East Asia’s energy mix. To illustrate, Indonesia’s RUPTL 2025-2034 plan, for new power capacity, progresses renewables significantly, but its first phase towards 2030, has fossil-fuel expansion remaining dominant (Yustika, 2025). Both Vietnam and Indonesia have Just Energy Transition Partnerships to transition away from coal, but Vietnam has no formal plan to retire coal, and new capacity is being built. Both countries have significant consumer and producer-facing fossil-fuel subsidies that distort price signals to consumers, disincentivizing use of cleaner energy (Climateworks, 2025).

- ─ Singapore leads in less mature energy technologies. It pioneers hydrogen and ammonia with pilot hydrogen imports expected by 2027. The new USD 3.7bn Future Energy Fund supports clean energy imports, grid modernization, and hydrogen/nuclear research. In carbon capture, Singapore explores cross-border CO2 transport with storage options in Australia, Indonesia, and Malaysia – both of which aim to become regional CO2 hubs and in advanced stages of developing regulation.

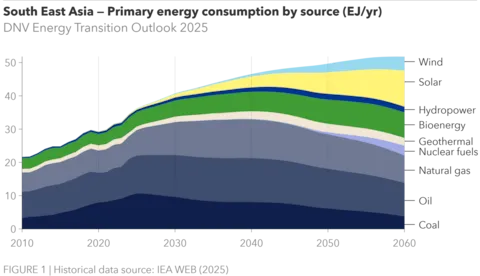

South East Asia’s (SEA) primary energy mix is dominated by fossil fuels today, accounting for 81%, on a par with the global average. Coal reliance diminishes slowly, but oil will remain at similar levels as today and natural gas will grow, although contributing an overall lower share of primary energy. Geothermal more than doubles from 1EJ to 2.3EJ in 2060, which is around 4% of the primary energy mix, the largest share of all regions.

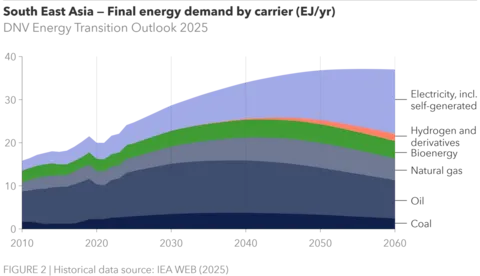

Fossil fuels dominate final energy, led by oil, driven by low levels of electrification in transport. Fossil fuels share in final energy demand will continue to grow, peaking in the early 2040s, before declining to slightly below today’s levels by 2060. Electricity grows quickly but only overtakes fossil fuels’ share by the late 2050s. Electricity will mostly meet new demand, as the population in the region grows and becomes richer.

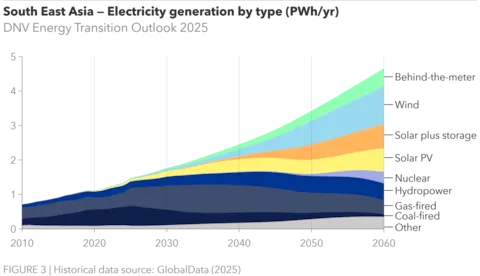

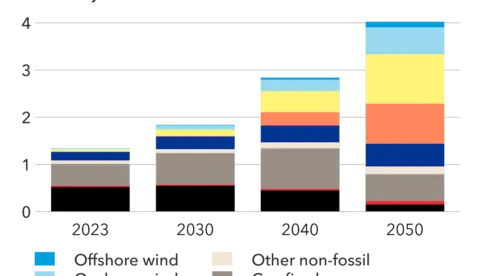

SEA’s electricity use will be around 3.5 times as much as today by 2060, and much of this new demand will be met by solar. Wind will grow to 23% and solar to 30% of electricity generation in 2060. Hydropower’s share will drop from 16% today to 11% by 2060, but the total capacity will more than double. Nuclear is expected to come online only in the 2050s, supplying around 7% of electricity in 2060.

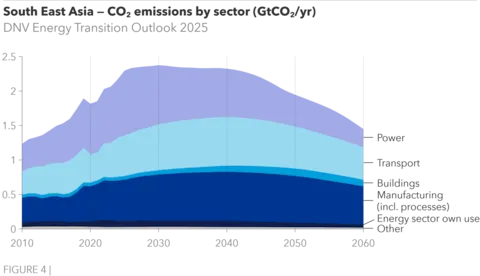

Carbon dioxide emissions in South East Asia are expected to peak around 2030, and to plateau just below this until a proper decline starts in the mid-2040s. Power is the main sector for decarbonization, reducing emissions nearly 70% by 2060, achieved by phasing out coal and uptake of solar. Transport sees a modest 17% decline, while manufacturing sees only a small decrease in emissions and buildings a slight increase.

South East Asia, a dynamic and resource-rich region, is in a prolonged period of rapid development. Since the inception of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 1967, the region has enjoyed robust improvements in living conditions, economic prosperity, and mostly peaceful stability between the ethnically, politically, and religiously diverse countries. Thanks to this stability and economic growth, the growing population is getting richer and is using more resources, pushing up energy demand and emissions.

Coal phase-out is slow

Dependence on fossil fuels is a major roadblock in the energy transition in South East Asia. Today, the region’s final energy demand is 68% fossil, dominated by oil (Figure 2). The fossil share will reduce to 44% in 2060, which is the highest proportion of all global regions except for the oil-and-gas-dominated Middle East and North Africa, and North East Eurasia.

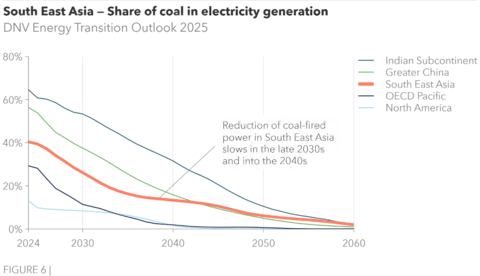

Reliance on coal remains strong across South East Asia. Indonesia and the Philippines are the two most coal-dependent countries, relying heavily on it to meet new electricity demand. In these two countries, coal accounts for over 62% of electricity generation today, higher than the regional average of around 40%. Today, the Indian Subcontinent and Greater China have greater shares of coal in electricity generation. However, Greater China reduces coal-fired power much quicker, with a compound annual growth rate of –9.3% to 2060 compared to –5.1% in South East Asia. Despite starting with a much higher coal share in 2024 (65%) and using nearly three times as much coal as South East Asia in absolute terms, the Indian Subcontinent reduces coal-fired power to reach the same coal share by 2060, highlighting South East Asia’s sluggish approach to phasing out coal (Figure 6).

Indonesia primarily relies on its prolific production of domestic coal; it is in the top three of global coal production and is the biggest exporter of thermal coal. Despite strong domestic demand in Indonesia, we expect the region’s coal production to continue its slow decline. The country has already registered a decline in coal exports so far in 2025, mainly due to weak demand from major markets India and China, and reduced demand from other markets like South Korea, Japan, and Vietnam (Maguire, 2025).

The region’s coal plants are some of the youngest in the world, with an average age of 15 years. Phasing out its coal plants early could lead to additional costs exceeding USD 270bn, including up to USD 130bn of capital that is yet to be recovered from coal plant investments in the region, highlighting the economic difficulty associated with phasing out assets earlier than the planned economic lifetime (Do, 2024; IEA, 2025). Early phase-out of coal would be particularly impactful in Indonesia, where thousands of people are employed in coal-reliant industries and several provinces’ local economies and job markets are dependent on coal-fired power plants.

Alongside Indonesia, Vietnam and the Philippines face similar challenges with early phase-outs. Several companies in these countries have adopted Energy Transition Mechanisms (ETM), a collaborative initiative championed by the Asian Development Bank (ADB). ETMs are an innovative financial instrument which aims to support early retirement of coal plants by leveraging concessional and commercial capital to retire or repurpose fossil-fuel plants on an accelerated schedule (ADB, 2023). ETMs will enable early retirement of the South Luzon Thermal Energy Corp plant in the Philippines and the Cirebon-1 plant in Indonesia, and Vietnam has been identified as another market for ETMs.

Phasing out fossil fuels requires targeted policies, such as carbon-pricing mechanisms and subsidy reforms. Several countries are conducting feasibility studies or pilots for carbon taxes and emissions trading schemes. Indonesia and Vietnam are using funds from the Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs) signed in 2022 to support the equitable energy transition. Vietnam has announced a timeline for phasing out coal-fired power plants to 2050: plants must meet carbon reduction standards by 2030 or face closure, inefficient plants which cannot be adapted will be closed by 2040, and all plants will be phased out or carbon capture technology will be used to achieve net-zero emissions.

However, these efforts remain fragmented and lack comprehensive coverage and political will, which limits their effectiveness. Looking ahead, countries like Indonesia, Singapore, and Brunei have set goals to phase out coal power in the 2040s, while others have a 2050 focus. To ensure a just and equitable transition, governments must also prioritize subsidy reforms, worker retraining, and community support programmes for fossil-reliant regions.

Gas a key transition fuel

After coal, gas is the next largest source of electricity in the region, accounting for around 30% today. It is also seen as a key transitional fuel, and thus we expect that the share of gas-fired power will grow until the late 2030s. Gas-fired power plants will likely play a role in providing a stable power source to meet the rising data-centre demand in the region.

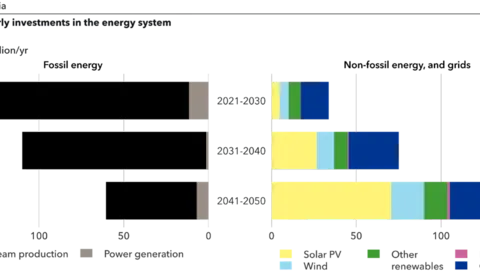

Local production is expected to increase, bolstered by deepwater discoveries in Indonesia and Malaysia in the past few years. In May 2025, Malaysia released new guidelines for developing regasification terminals, which are critical for LNG imports, exemplifying plans for the region to leverage gas resources in the medium term. As countries embark on decarbonization pathways that involve gas as a transition fuel, it is attracting investment from major energy companies globally. Investment in upstream fossil-fuel production in the 2020s and 2030s is focused on security domestic production and limiting dependence on imports, especially gas (Figure 7).

Road transport is driving oil dependence

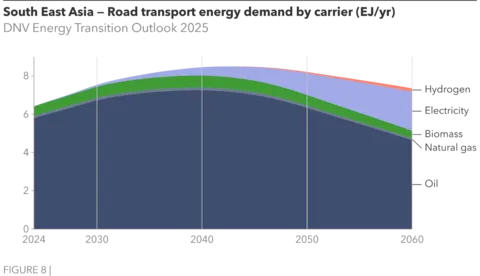

Transport represents a huge opportunity for decarbonization in South East Asia via electrification of the road transport fleet. Today, road transport oil demand is 5.8 EJ, which accounts for around 57% of the region’s oil demand. We project that road transport oil demand will continue growing as the population grows and become wealthier, increasing the demand for passenger vehicles (four-wheelers). We expect oil demand from road transport to grow to a peak of 7.3 EJ in the early 2040s, before declining to around 4.7 EJ in 2060 as electrification becomes more common (Figure 8).

The total number of vehicles for personal and commercial use, including two- and three-wheelers, will nearly double from around 325 million today to 581 million in 2060. The majority of these vehicles will be two- and three-wheelers, as South East Asia has the second largest fleet of these behind the Indian Subcontinent. We estimate that around 99% of the two- and three-wheel fleet will be electrified by the early 2040s. Despite this quick growth, the share of two- and three-wheelers in the total vehicle fleet drops from 71% today to 61% in 2060, reflecting the income-influenced change in demand patterns for vehicles.

Long road ahead for EV adoption

Compared to two- and three-wheelers, passenger vehicles electrify more slowly. Passenger vehicles today are almost entirely ICEVs. We anticipate uptake to EVs to increase in the 2030s and 2040s (Figure 9), primarily through demand in Malaysia and Thailand, which are the leading EV markets in the region, and to a lesser extent Vietnam and Indonesia. The region also looks to place itself as an alternative EV manufacturing hub. Thailand is already attracting global investment, particularly from Chinese car manufacturers, with aims to secure domestic production of Toyota EVs, and to reach 50% EV manufacturing by 2030. Vietnam is continuing production of VinFast EVs for domestic and international markets, although the domestic uptake remains low.

EV adoption will continue to lag nearby regions like Greater China and OECD Pacific. A major factor that could contribute to higher EV adoption in the region is to implement more supportive policies, like EV adoptions targets and consumer incentives at point of sale. In cases where policies exist – like the 25% EV sales share by 2030 in Indonesia, consumer subsidies and slashed road taxes for EV purchases in Malaysia, and EV public transport programmes in the Philippines – they lead to some increased EV share in the country but are often too weak to significantly impact EV adoption in the region. Stronger policies across more of the countries in South East Asia must be pursued to influence increased EV adoption, as well as build-out of supportive battery charging infrastructure to increase accessibility and convenience for EV users.

Electricity demand is surging

Electricity demand is surging, driven by economic growth, digitalization, a growing fintech and data centres sector, and an increasingly richer population. This demand is bringing into focus the key ongoing challenge facing the region: balancing economic growth, energy security, and climate and environmental objectives. Whilst most of new electricity demand will still be met by fossil fuels in the coming few years, renewables are gaining momentum, particularly in Vietnam (the regional leader for renewables installations), Thailand, and the Philippines.

Solar dominates new renewables installations, as South East Asia’s tropical geography provides consistent and abundant solar irradiance throughout the year. In contrast, wind uptake is slower as there are fewer suitably windy locations in the region, and they tend to be further from population centres, adding transmission costs. Policy priorities have leaned towards solar, supporting its uptake through feed-in tariffs. Investments in green-tech manufacturing in the region have vastly favoured solar over wind. Solar and wind are the main sources of renewable energy in the region’s transition, supported by hydropower capacity in Lao PDR and Vietnam, and geothermal power in the Philippines and Indonesia.

ASEAN targets renewables having a 35% share in installed power capacity by 2025. Our analysis shows that South East Asia (which includes all the ASEAN member states) has nearly reached this target, with around 33% renewable power capacity today and 35% expected in the next two years (Figure 10). We anticipate that the share of renewables in electricity generation will grow quickly in the 2030s, largely due to the quick uptake of solar and solar+storage technologies. At a regional level, renewables will primarily meet new electricity demand later in the coming decades rather than displacing fossil fuels to any significant degree. We anticipate that displacement of fossil fuels may only occur in the 2050s, as shares of gas in electricity decrease.

Vietnam continues to lead the region in renewables installations. Thus, plans for Vietnam’s state-owned power utility to retroactively cut subsidies to wind and solar have raised alarm among project owners and investors. Subsidies have been instrumental in propelling Vietnam forward to the top spot in the region for share of electricity from wind and solar. A letter from both Vietnamese project owners and international investors urged the Vietnamese government to reconsider changes to the power purchase agreements (PPAs), stating that the changes could jeopardize up to USD 13 billion in investments and plans laid out in its Power Development Plan 8 (PDP8) (Francesco, 2025).

Battery energy storage systems (BESS) are emerging as a strategic pivot, with deployment rising alongside solar projects. The Philippines, Thailand, and Malaysia are leading this trend. Malaysia’s Large Scale Solar (LSS) 6 programme, with bidding planned for Q3 in 2025, marks the country’s largest solar rollout (and for the first time, paired with BESS). The bidding is expected to unlock contracts worth USD 3.4–4.1billion in the next two years. Additionally, Thailand has launched its first national BESS tender, while Vietnam has incorporated BESS-capable renewables projects into its revised PDP8.

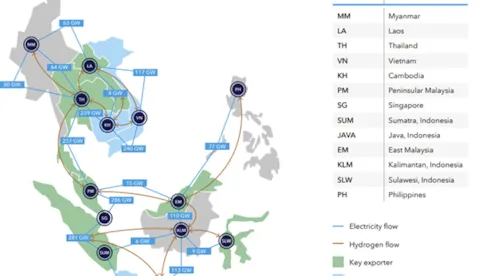

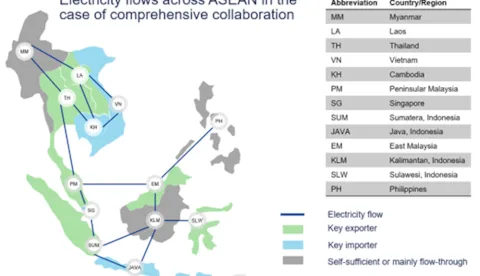

Regional interconnectivity is key

The ASEAN Power Grid (APG) is the leading collaboration initiative to connect electricity of ten member countries with the aim of fully integrated grid operation by 2045. It aims to support economic development and energy security through effective sharing of renewable resources, thus reducing reliance on fossil fuels for electricity generation. The Lao PDR–Thailand–Malaysia–Singapore Power Integration Project (LTMS-PIP) – which transfers hydropower electricity from Lao PDR to Singapore via Thailand and Malaysia – is exploring an Indonesia–Malaysia link as part of Phase 2 of the project. Feasibility studies initiated by Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand are exploring further regional renewable energy interconnection corridors, contributing to APG’s momentum.

DNV’s 2024 ASEAN Interconnector Study: Taking a Regional Approach to Decarbonization provides an in-depth analysis of the ASEAN power sector. The report identifies that up to USD 800 billion could be saved through comprehensive regional collaboration when compared to individual countries pursuing decarbonization goals without cooperation. Even moderate collaboration could lead to USD 300 billion savings. The significant cost and space saving benefits encompass power interconnectors, hydrogen networks, and energy storage technologies and infrastructure. Countries with a diversified supply of solar, wind, and hydropower resources (e.g. Thailand and Lao PDR) will be the main exporters of clean energy within the region.

Nuclear on the long-term horizon

South East Asia is home to a single nuclear power plant which has never produced energy, built in the 1970s across the bay from Manila, the Philippines. We forecast that nuclear will continue to play little role in the South East Asian energy mix in the coming decades, with uptake occurring slowly from the 2040s before quickening in the 2050s. While Vietnam has plans to open its first nuclear plant by 2035, most of the region’s capacity is likely to be installed in Indonesia. By 2060, South East Asia will have around 60 GW of nuclear capacity, as much as is installed in Greater China today.

Tariffs, tension, and thinning development aid

South East Asia is facing three simultaneous challenges: high US tariffs, rising border tensions within the region, and reduced aid from wealthier nations. This turbulence is putting the region’s economic resilience and political cohesion to the test, reminding all countries of the overarching challenge – balancing economic growth, energy security, and energy transition and climate objectives.

Countries in South East Asia face the full range of US tariffs, from the 10% base rate in Singapore to 40% in Lao PDR and Myanmar, some of the highest in the world. Most of the major economies face tariff rates of 19% to 20%. Tariffs may impact the competitiveness of renewable energy technology production in South East Asia. Although Vietnam’s tariff rate is 20%, lowered from the earlier announced 46%, trans-shipments from third countries through Vietnam will face a 40% levy. This is likely targeting goods produced in Vietnam with significant Chinese components, keeping in line with the American bipartisan objective of reducing China’s influence in the global supply chain (Cheng, 2025).

Tariffs will affect trade policy and, probably, the economic livelihoods of millions of people in the region. Increased uncertainty and a volatile external trade landscape could push countries within South East Asia to deepen economic ties, which is aligned with existing collaboration goals within ASEAN. However, some relations within the region have deteriorated rapidly due to border conflicts, the main example being Cambodia and Thailand. The conflict impacted the trade of goods across the border, causing the fuel price to skyrocket in Cambodia, and prompted nearly one million migrants to return home, greatly impacting livelihoods and economic activity (Chhorn, 2025). Conflicts reduce potential for collaboration, endanger or damage infrastructure, and often draw away resources and demote energy and climate concerns down a country’s priority list, ultimately slowing the energy transition.

The impacts in the economy are from US tariffs, and rising border tensions are exacerbated by reduced aid provided to the region by wealthier nations, including from big donors like the US, the EU, and Japan (OECD, 2025). Highly aid-dependent countries like Cambodia, Lao PDR, and Myanmar will feel the impact most, and bigger economies in the region will see scaled back programmes in targeted fields like climate action and skills and training. Consequently, countries must then look to domestic revenue and public-private partnerships to fund development. Support from these donor nations, and other neighbours like China and Australia, is vital for South East Asia’s transition.

Significant risk for climate change impacts

Many countries in South East Asia have historically contributed very few emissions compared to wealthy countries which industrialized earlier. But South East Asia bears a disproportionate burden of the resulting climate changes: it is one of the most disaster-prone regions in the world, its geographies and climate rendering it particularly vulnerable.

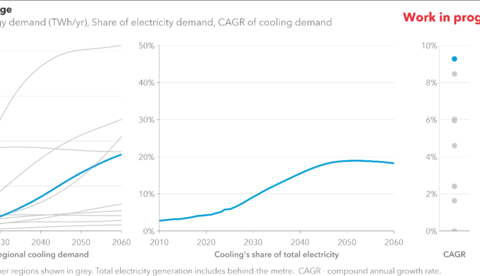

Extreme heat is a significant concern for South East Asia; and Asia as a whole is warming at twice the global average. Heatwaves are arriving earlier, lasting longer, and becoming more frequent. Temperature records are falling; Myanmar set a new national temperature record of 48.2°C in 2024 and countries like the Philippines, Thailand, and Indonesia are experiencing more instances of the heat index reaching 'dangerous’ and above (Tachev, 2025; WMO, 2025).

Combined with high humidity levels, South East Asia regularly reaches wet bulb temperatures, posing a significant health threat to the population, especially vulnerable groups, and causing disruption to economic activities. The demand for cooling in South East Asia is surging to cope with warming conditions. Cooling energy demand grows fastest there among all the ETO regions

In addition to extreme heat, the region is also under threat from more frequent and severe climate events like tropical cyclones, intense rainfall, flash flooding, landslides, and drought conditions. These events are threatening South East Asia’s tropical forests, which are home to some of the richest biodiversity in the world. Rising sea levels and storm surges are also putting infrastructure and millions of people at risk, especially in coastal cities such as Jakarta, Ho Chi Minh City, and Yangon.

Pacific Islands in peril

The Pacific Islands are under immense threat from climate change. Ocean warming, ocean acidification, and sea-level rises well above the global average are threatening livelihoods in the Pacific – 90% of the population lives within five kilometres of the coast and half the infrastructure is within 500 metres (WMO, 2024).

In 2023, Tuvalu – a small island nation in the Pacific Ocean – signed an agreement with Australia, which is considered a world-first for climate migration. Australia has agreed to grant visas to 280 Tuvalu citizens per year to relocate to Australia in the face of rapidly rising sea levels and increasingly uninhabitable land. The first ballot, which opened in June 2025, had nearly one third of Tuvalu’s entire 10,000–strong population enter, illustrating how urgent and serious climate change impacts are in the Pacific (France-Presse, 2025).

Carbon pricing mechanisms gaining momentum

The regional average carbon price is comparatively low in the global landscape – projected to reach around USD 10/tCO2 in 2030 and USD 25/tCO2 in 2040. Singapore is the regional leader with its carbon tax, which rose to USD 25/tCO2 in 2024 and has an outlined trajectory to progressively rise to between 50 and 80 USD/tCO2 in 2030.

Several countries are exploring the feasibility of ETS or pursuing pilot projects. A proposal for an ETS, a carbon tax on select products, and a carbon border adjustment on some imported products, is in the works in Thailand with existing plans to launch its voluntary carbon credit scheme. Indonesia is launching the second phase of its carbon trading scheme Nilai Ekonomi Karbon (NEK), which aims to cover coal-fired power plants which are not grid-connected, and gas-fired power plants. Malaysia’s Bursa Carbon Exchange, launched in 2023, is set to expand to include mandatory reporting for large emitters this year. ASEAN has also explored the feasibility of a regional carbon market, signalling a desire for increased coordination in climate policymaking.

Several large economies in the region are planning to implement schemes and policies to support emissions reduction, with CCS initiatives gaining momentum. Through continued projects in Pulau Bukom and Jurong Island, Singapore is reinforcing its role as the regional hub for CO2 storage, which compliments its role as a global shipping hub. Malaysia’s state-owned oil enterprise Petronas is proceeding with its flagship CCS project Kasawari, as well as developing other offshore CCS projects like Duyong and Lawit. Thailand’s first CCS project has been approved for its Arthit gas field, with operations expected to commence in 2028. Indonesia is in the planning stages and has around 12 potential CCS projects aiming to be operational by 2030. Indonesia and Malaysia are together advancing regulatory frameworks for cross-border CCS projects.

Emissions

The annual energy-related CO2 emissions from South East Asia are projected to peak around 2030, and to plateau just below this peak at around 2.3 Gt, before a proper decline starts in the mid-2040s. Coal is currently the largest contributor to emissions, however we forecast that oil will match and then surpass coal emissions in the early 2030s. This trend reflects the region’s ongoing dependence on oil for road transport. Power is the sector that decarbonizes the most, reducing emissions nearly 70% by 2060, compared to today (Figure 13). This is achieved largely through phasing out coal and building out solar and solar+storage.

In the context of global climate policy, several countries within South East Asia have net-zero goals. Lao PDR, Cambodia, Vietnam, Malaysia, Singapore, Papua New Guinea, and several Pacific Island states, are all targeting 2050, and Myanmar proposes to do so. Indonesia has pledged a 2060 net-zero target, while Thailand targets 2065, and the Philippines has no target. Although several of these targets are enshrined in law, comprehensive policy plans outlining the path to net zero are often lacking.

The country pledges and NDCs imply a regional goal of restraining GHG emission increases to no more than 281% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels. Discrepancies in targets and forecasts arise due to uncertainties concerning whether targets include non-energy-related CO2 emissions. Our Outlook forecasts energy-related and process-related CO2 emissions (after CCS and DAC) increasing 484% by 2030 from 1990, suggesting that countries will fall short of meeting their pledges.

Regarding the emissions trend towards mid-century, energy- and process-related CO2 emissions will be approximately 1.9 GtCO2/yr in 2050, 11% below 2024 levels and around 19% lower than the projected peak emissions in 2030. Energy-related CO2 emissions will be approximately 1.4 GtCO2/yr by 2060, a reduction of around 33% from today’s levels and around 39% lower than the projected peak emissions level in the early 2030s. Although progress will be made with cutting emissions long term, policies and initiatives must be strengthened and deployed sooner to achieve net-zero targets.

Policy summary

A non-exhaustive list of sector policy initiatives, emphasizing the 2024 to 2025 period

|

Climate targets - Key countries Malaysia, Singapore and Vietnam target net-zero by 2050, Indonesia by 2060 and Thailand by 2065 |

||

|

Sector |

Policy details and example initiatives |

Mechanism(s) |

|

Power |

> Renewables (RE) targets include Vietnam for 48% of capacity in 2030, 63% in 2050, Malaysia for 40% in 2035, 70% by 2050, Thailand for 30% by mid-2030s, 74% by 2050 > Vietnam targets 6-17 GW offshore wind by 2035 |

Feed-in tariffs (FiTs), RE auctions (PPAs) , fiscal incentives such as tax exemptions/deductions |

|

> Battery energy storage systems (BESS) promotion includes Singapore, Philippines, Malaysia, Vietnam, Thailand for RE + BESS |

Linked to auction, procurement schemes, incentives for RE power |

|

|

> Singapore plan for 1.2 GW hydrogen-ready gas units to start operation by 2027-2029 |

Competitive tenders / auctions |

|

|

> Nuclear: Several countries in planning phase, including Indonesia for 10 GW capacity by 2040.Vietnam for 6.4GW by 2035, 8 GW by 2050. Thailand for adoption of SMRs |

International nuclear financing becoming more available, e.g. nuclear funding ban lifted by the World Bank (June 2025) Cooperation, e.g. Rosatom-Vietnam (January 2025) |

|

|

Grids |

> Vision of integrated grid by 2045 ASEAN Power Grid (APG). > Cambodia, Malaysia and Singapore signed the COP29 Global Energy Storage and Grids Pledge |

International finance, including the launch of the ASEAN Power Grid Financing Facility (APGF) with pledges from the Asian Development Bank and the World Bank (August 2025). |

|

Hydrogen |

> Singapore plans hydrogen/derivatives use in power and shipping sectors and initiated regulatory framework development, including for imports (August 2024). > Indonesia and Malaysia explore low-carbon hydrogen zones, but high costs and regulatory uncertainty are stalling progress. |

R&D funding in Singapore’s Low Carbon Energy Research (LCER) Programme. Low-carbon hydrogen and ammonia tenders |

|

CCS/DAC |

> Feasibility studies for power system deployment in Singapore and initial plan for piloting in coal and oil and gas sectors in Vietnam > Cross-border storage agreements, including Malaysia for CO2 from Japan, Indonesia for CO2 from Singapore > Malaysia and Indonesia at an advanced stage of developing regulation, aiming to become regional storage hubs. |

General lack government funding for CCS outside the oil and gas sectors. Singapore Grant Programme for Feasibility studies (October 2024 Bilateral agreements on overseas storage Carbon pricing under development |

|

Transport |

> Biofuel-blending rates in road fuels in several countries, including Indonesia (35%), Malaysia (30%) by mid-2020s. > EV ecosystem promotion by ASEAN for EV manufacturing, and uptake ambitions. Singapore with ICE phase out by 2040. > Plans for SAF production and blending ratios in aviation, leaning on mandates rather than incentives |

Mandates on biofuels EV purchase incentives in e.g. Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand ICE ban ICAO’s Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA) |

|

Manufacturing |

> Singapore aims for energy and industrial sector decarbonization. A S$90 million research programme includes focus on hydrogen use and production of greener chemicals and fuels > Malaysia expanded its green investment tax allowance (GITA) to include green hydrogen |

Government funding to research and development

Tax reduction |

|

Buildings |

> Nationally, energy efficiency goals, building codes and urban planning, and growing focus on district cooling with Singapore in the lead. Regionally, the ASEAN-wide Programme for Energy Efficiency, PEEB ASEAN kicked of May 2025 |

Standards International partnership grants, e.g. PEEB funding from France Mandatory energy audits (Singapore)

|

References

ADB – Asian Development Bank (2023). New Agreement Aims to Retire Indonesia 660-MW Coal Plant Almost 7 Years Early. https://www.adb.org/news/new-agreement-aims-retire-indonesia-660-mw-coal-plant-almost-7-years-early

Cheng, T.-H. (2025). Implications of U.S. Tariffs on Southeast Asia: Navigating The Trade Tumult. https://www.sidley.com/en/insights/newsupdates/2025/08/implications-of-us-tariffs-on-southeast-asia-navigating-the-trade-tumult

Chhorn, D. (2025). Triple shock threatens Southeast Asia’s development model | Lowy Institute. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/triple-shock-threatens-southeast-asia-s-development-model

Climateworks (2025). Progress on just energy transitions in Vietnam and Indonesia. May 7. https://www.climateworkscentre.org/resource/progress-on-just-energy-transitions-in-vietnam-and-indonesia/

Do, T.N. (2024). ‘International cooperation is critical to Southeast Asia’s clean energy transition’, East Asia Forum Quarterly, 16(2). https://eastasiaforum.org/quarterlies/remaking-supply-chains

France-Presse, A. (2025). ‘Nearly a third of Tuvalu citizens enter ballot for climate-linked visa to relocate to Australia’, The Guardian, 26 June. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/jun/26/nearly-a-third-of-tuvalu-citizens-enter-ballot-for-climate-linked-visa-to-relocate-to-australia

Francesco, G. (2025). ‘Vietnam retroactively cuts subsidies for some solar, wind farms, investors’ letter says’, Reuters, 22 May. https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/climate-energy/vietnam-retroactively-cuts-subsidies-some-solar-wind-farms-investors-letter-says-2025-05-22

IEA (2025). Southeast Asia – World Energy Investment 2025 – Analysis, IEA. https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-investment-2025/southeast-asia

Kelly, B., Wester, S. (2025). ‘ASEAN Caught Between China’s Export Surge and Global De-Risking’. Asia Society Policy Institute. February 17. https://asiasociety.org/policy-institute/asean-caught-between-chinas-export-surge-and-global-de-risking

Maguire, G. (2025). ‘Indonesia coal exports post rare decline so far in 2025: Maguire’, Reuters, 9 May. https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/indonesia-coal-exports-post-rare-decline-so-far-2025-maguire-2025-05-09

Met Office (2024). Southeast Asia climate risk report. https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/services/government/international-development/southeast-asia-climate-risk-report

OECD (2025). Cuts in official development assistance: Full Report, OECD. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/cuts-in-official-development-assistance_8c530629-en/full-report.html

Tachev, V. (2025). ‘The 2025 Heatwave in Southeast Asia: A Window Into the Future’, Climate Impacts Tracker Asia, 7 May. https://www.climateimpactstracker.com/2025-heatwave-in-southeast-asia

WMO (2025). Rising temperatures and extreme weather hit Asia hard, World Meteorological Organization. https://wmo.int/news/media-centre/rising-temperatures-and-extreme-weather-hit-asia-hard

World Meteorological Organization (2024). Climate change transforms Pacific Islands, World Meteorological Organization. https://wmo.int/news/media-centre/climate-change-transforms-pacific-islands

Yustika, Mutya (2025). ‘The risks of fossil fuel dependence in Indonesia’s Electricity Supply Business Plan (RUPTL) 2025–2034’. Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. June 23. https://ieefa.org/resources/risks-fossil-fuel-dependence-indonesias-electricity-supply-business-plan-ruptl-2025-0