When the tables turn for investors in renewables

Last year, for the first time in history, global spending on wind and solar assets was greater than investment in new and existing oil and gas fields. There’s no doubt the energy transition is accelerating, but there’s a challenge looming on the horizon. Will today’s capital available from experienced financiers and investors in clean energy be enough?

Last year, for the first time in history, global spending on wind and solar assets was greater than investment in new and existing oil and gas fields. There’s no doubt the energy transition is accelerating, but there’s a challenge looming on the horizon. Will today’s capital available from experienced financiers and investors in clean energy be enough?

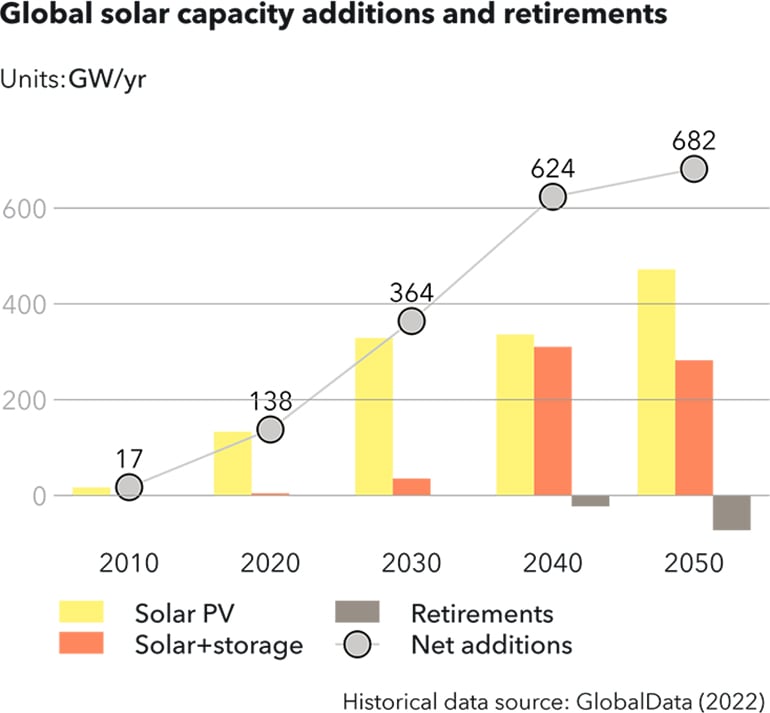

Last year alone saw 249 GW of new installed Solar PV capacity, according to Bloomberg BEF. DNV expects this to grow to 364 GW per year by 2030, up from 138 GW per year in 2020. Offshore wind has an equally promising future. DNV expects that by mid-century, 31% of the world’s electricity will be supplied by wind. Recent renewed focus on energy security and energy independence is only strengthening the case for further renewables build-out globally.

Figure 1: Global solar capacity additions and retirements (Source: DNV ETO 2022)

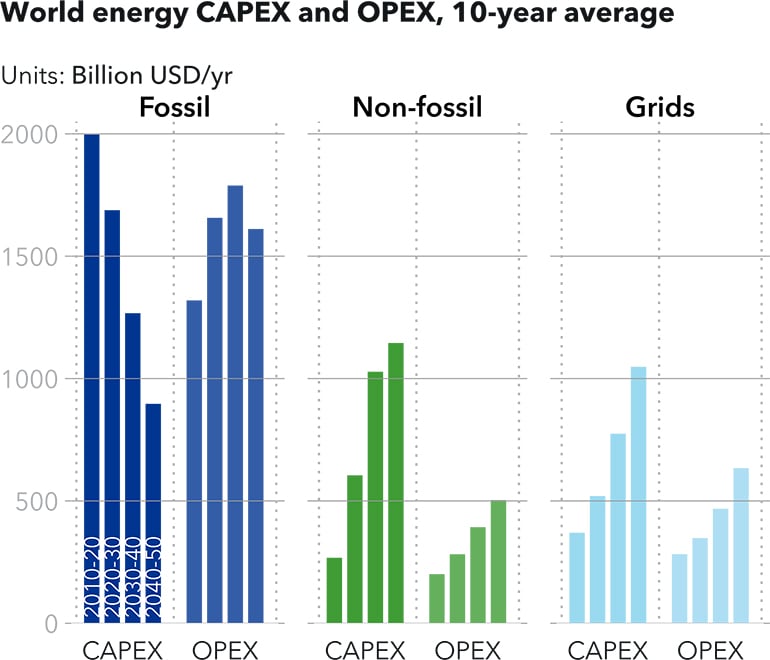

But there is a challenge looming on the horizon: the financing challenge. DNV forecasts that clean energy expenditure will increase to around USD 1.9trn per year in 2030. A massive redirection of capital from fossil energy expenditure to non-fossil energy is needed to finance this growth. Today’s capital available from experienced financiers and investors in clean energy might simply not be enough. Recent price volatility and cost inflation, at a time when the market is moving away from subsidized income streams to fully merchant ones has caused some investors to rethink their investment strategies and revalue their existing renewable portfolios. The years of abundant capital, available at low cost, chasing few renewable energy projects might soon be replaced with a situation of renewable investments competing for cheap capital and favourable financing structures – the tables are turning for renewable developers and its investors.

Figure 2: DNV forecasts yearly capital expenditure (CAPEX) for non-fossil investments to grow rapidly. The expenditures are presented as an average expenditure over 10 years leading up to 2020, 2030, and so on (Source: DNV ETO 2022)

A shift in financing structures

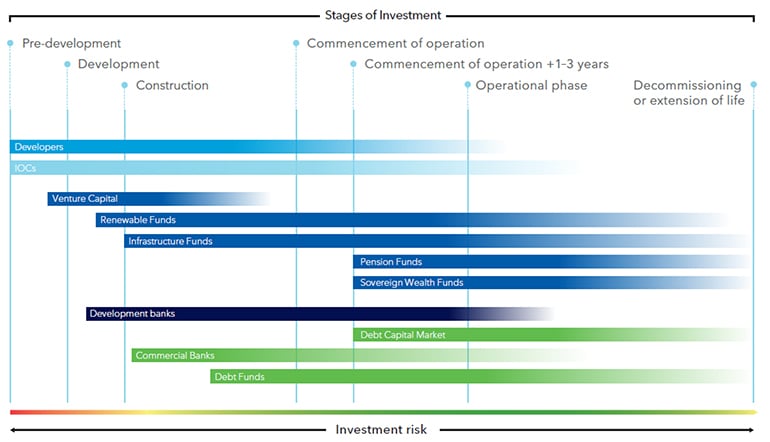

Over the last couple of years, DNV has observed investments shifting away from assets to equity stakes in companies. This brings a different risk profile, moving away from structured project deals towards portfolio thinking and corporate risk. This move shifts the value of projects to future cashflow at various stages of development (the so-called “project pipeline”) and the management team that needs to deliver this project pipeline. For example, by investing in renewable developers, the risk profile moves away from typical infrastructure investments with high capital expenditure, secure cashflows and little market correlation, towards a higher risk profile, with exposure towards the value proposition of the company, rather than solely the sum of projects it consists of.

During the last two years multiple platform transactions and direct investments in developers have closed. With the expected growth in renewable power generation combined with the high-power prices, DNV expects many more to come. This shift in financing structures, combined with the envisaged growth of renewables and therefore the need for new capital flowing to renewables, demands a robust risk approach.

Figure 3: Investor appetite along the stages of investment. Commercial banks, renewable funds and even infrastructure funds are moving to the development stage (Source: DNV Financing the Energy Transition 2021)

How to value a pipeline of projects?

But how do you value a project pipeline? How do you deal with the uncertainties inevitably correlated to the development phase? How likely can the company business case expand successfully to other markets or technologies with different characteristics? What additional value, and risks, do investors see with this change of investment strategy?

DNV’s perspective is that it requires a different risk approach, which can be structured around three pillars, and which might differ from country to country:

- Top-down review of Company’s main market drivers, the so called “external factors”. Examples are national renewable energy targets, competition, grid planning bottlenecks, permitting procedures and public perception.

- Top-down review of the Company’s internal organization, the so called “internal factors”. Examples for review are the company’s track record, local knowledge, the organization’s governance model, the standardization of project milestones to categorize the pipeline, and the scalability of the business model per technology.

- Bottom-up review of a selection of projects, the so called “deep dive”. Key de-risking factors are region specific, but typically follow the logic of securing the land, obtaining the necessary permits, and signing the grid connection agreement.

The technical maturity of the project develops over time, with procurement lead times and costs as a focus area. The commercial maturity evolves similarly, with an initial route to market in place at an early stage, and a more detailed business case developed when moving closer to construction. Offtake is a focus area, whether related to the status of subsidy applications, PPA terms, or in case of a long merchant tail, a power price analysis for the project.

The combination of these three pillars provides an independent and realistic estimate of the company’s ability to realize its project pipeline, in other words its probability of success. The estimates help investors to better understand the risks related to the company’s value proposition, scalability, and governance structure. This approach will create an increased level of certainty, and thereby reduce risk.

High risk, low return?

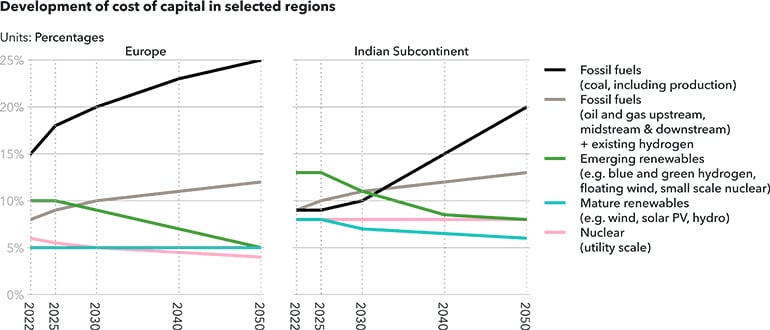

There is a concern that the combination of the vast amounts of capital required, the need for new pockets of money with different risk perception and return requirements, the increased exposure towards price volatility in subsidy-free projects, and the shift in financing structures towards direct investments in developers, will increase capital costs. With the cost of capital being one of the key cost drivers for capital intensive projects like renewables, increasing capital costs means a more expensive, and therefore slower energy transition.

So, what happened to the optimistic view that the transition is accelerating? One way to keep the cost of capital low lies in portfolio thinking. If the risks are understood, they can be managed by actively taking a portfolio approach, combining different asset classes, offtake agreements and geographies in one development platform to balance risk, cashflows and the needed returns. Direct investment in companies automatically offers a more diversified investment than an infrastructure asset investment and could offer reduced risks when conservative and robust estimates are made around the project pipeline.

Another solution lies with policy makers enabling fast and stable policy implementation. When Germany announced last year that it would build floating LNG terminals that were operational within half a year, many said it was impossible in a country known for its infrastructure delays, like Berlin’s new airport. But it was possible, and the terminal opened after just five months. This speed should be used as a model for the future build-out of critical energy transition infrastructure, to enable us to act in the window of opportunity for keeping temperatures well below 2 degrees. Stable regulations, transparent permitting processes and speed all drive risks, and therefore costs of capital, down.

A third answer that supports continued low costs of capital comes from the formidable starting point for solar PV and wind in a world that needs to decarbonize. The business case is sound with costs to bring the electricity to market most often lower than the electricity prices obtained. And its competitive edge will only increase over time, with falling costs and ever maturing technology. On the other hand, the fossil-based competition is starting to feel the pinch, CO2 prices are on the rise globally and as an example, in Europe crossed the 100 euros per tonne bar late in February 2023, increasing costs for fossil fuelled power plants to generate electricity, giving an added boost to electricity generated by renewables.

These arguments bolster DNV’s view of the continued low costs of capital for mature renewables globally, as graphically depicted in figure 4.

Figure 4: DNV forecasts continued low costs of capital for mature renewables (Source: DNV 2022)

Accelerating the deployment of capital

While the energy transition will be complex, there is real appetite and drive for innovation amongst private capital providers. A massive redirection of capital relies on a change in mindset: to recognize the carbon budget is finite and to place it at the centre of decision-making.

Will it be a smooth ride to deploy 1.9 trillion US dollars towards clean energy in 2030? No. Will it be possible? Absolutely, and necessary.

When investors take the next step in the energy transition with balanced portfolios of different assets like solar, wind and energy storage, offtake agreements and geographies, they will be supported by the sound business case for renewables.

To find out more about the financing challenges and opportunities in development platforms, you can join our panel debate. With insights from:

- Sunniva Bjørnstad, Senior Partner in HitecVision

- Erik Sneve, CEO of Magnora

- Roel Jouke Zwart, Head of section Nordics, Energy Markets & Strategy, DNV

- Martijn Maandag, Director Due Diligence in DNV.

We will focus on how to value a pipeline of projects, and how risks can be mitigated by combining different assets into one company.

Click here to register to attend in person in Oslo or the livestream from anywhere in the world.

3/9/2023 8:00:00 AM