The paralysing paradox at the heart of the global energy transition

Climate change is real, man-made and needs urgent action to prevent catastrophic impact on our world and our way of living. As a result, most governments, including the UK, have defined long-term targets to reduce emissions and aim for net zero around 2050.

(This article was first published in the Financial Times 4 June 2024)

However, paradoxically, at the same time, we see a clear system inertia that maintains the status quo of a fossil-fuel-dominated society to the extent that both DNV’s global and UK Energy Transition Outlook (ETO)1 forecast that the stated ambition under the Paris Agreement will not be met on the current trajectory. For the UK, DNV’s forecast shows that fossil fuels only very slowly disappear from the energy system, reducing from the current 80 per cent share of the primary energy supply to 50 per cent by 2040 and still delivering 35 per cent of the total supply even by 2050! And this inertia persists throughout the energy system2.

For example, there is a clear consensus that electrification sits at the heart of the energy transition – it reduces overall demand because of the improved efficiency and allows direct greening of the overall primary energy supply through the build-out of low carbon generation capacity. So unsurprisingly, all net-zero scenarios call for the rapid build-out of new electricity infrastructure both for renewable generation and for the expansion of the grid.

However, the pace of this transformation has been incremental. Planning and permitting cycles for new renewable capacity and new grid transmission lines are slow and waiting times for connection to the grid can still take up to 5-10 years. There is also still opposition from local communities regarding the impact of such infrastructure development on their immediate environment. These are key reasons why in DNV’s forecast we see the electricity grid being a blocker, rather than an enabler of the energy transition.

In addition, inertia is increased because there is a lack of incentive for the end consumer to embrace electrification. The current electricity market design in the UK results in an electricity price which is four times higher than the equivalent cost of natural gas per KWh 3– partially linked to environmental levies on electricity. With the current cost of living crisis, this will actively reduce the drive for consumers to consider electrical alternatives to gas and petrol, even if electrical systems are more efficient.

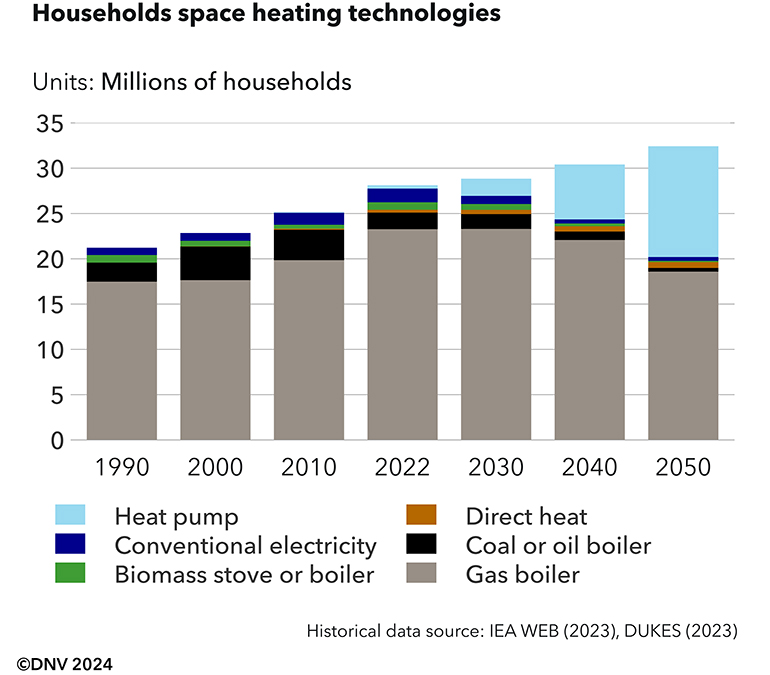

This also affects one of the more difficult areas for decarbonization: heating for homes, which will require phasing out gas boilers in 23mn UK households4. A significant part of the solution will be the replacement of these boilers with heat pumps and consequently, there are ambitious plans to ramp up heat pump installations to more than 1mn per year by 2030. But in the real world today, our analysis shows that installation rates reach just over 300,000 per year over that period5, with home-owner concerns about running costs, the need for improving insulation of homes and a supply chain that is struggling to scale up. Our forecast shows that for the next 5-10 years actual heat pump installations are likely to be dwarfed by nearly 1.5mn like-for-like gas boiler replacements each year, locking in many households to gas for years to come.

So, whilst we have achieved significant progress in the UK in terms of emission reductions, it can be argued that we have addressed mainly the low-hanging fruit. The next steps will require fundamental changes in the actual energy system closer to the end-user – physical changes to heating, transportation and manufacturing equipment, including complex, high-cost impact decisions on the optimum way to decarbonize various sectors. And to date, we see that governments are reluctant to take these tough decisions and instead defer them to the next budget or election cycle.

In summary, the energy transition is held back by inertia characterised by an incremental approach, driven by the individual consumer rather than the overriding public interest and locked into the existing fossil fuel infrastructure due to market design and consumer convenience.

The combined impact of the above factors is the paradox: even though we are all aligned on the long solutions and targets, the inertia of the incumbent fossil fuel system is likely to allow fossil fuels to dominate our energy mix for the next decade.

7/9/2024 8:36:00 AM