After a two-day lease auction in California, a first on the west coast of the U.S., there are a couple of key observations which could be regarded as disruptive with respect to the New York Bight’s ground-breaking highlights. Less active bidders (only seven out of the 43 qualified bidders participated in day 1) and lower acreage prices set a new tone in the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM)’s offshore wind leasing path. These observations confirm what appear to be the start of an acreage price relaxation trend first observed in the Carolina Long Bay’s auction in May 2022.

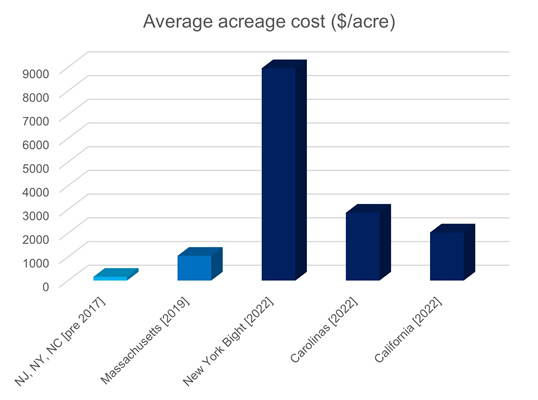

Much like the way DNV experts pointed out the need for cautious analysis of the causes leading to the surging acreage prices compared to the previous global benchmark (see Figure 1) following the New York Bight auction, after the California auction DNV confirms a clear drop in the competitiveness levels to obtain a site. This is not necessarily bad news for the industry; in fact, it may be good news.

Figure 1 – 2022 NY Bight, Carolinas and California Auction acreage costs

DNV considers the lower bid prices to be the outcome of a combination of root causes. With a total bid amount of USD 757,100,000 across all lease areas, bid price levels per acre have dropped in average 75% compared to the NY Bight and 30% compared to the Carolina Long Bay’s lease sales.

|

|

|

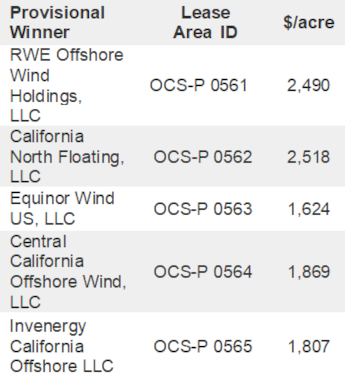

Figure 2 – Bid Prices for California Leases

As a less mature technology than its fixed-bottom counterpart, floating wind still has a road ahead to achieve equivalent levels of commerciality – and this is reflected in the auction bid prices. The great news is that this is only the beginning for the floating wind space, a market that has the potential to compete in LCoE with the fixed-bottom segment, according to DNV's Energy Transition Outlook. Floating wind can unlock massive offshore acreage in deeper waters for the deployment of offshore wind projects. This first floating wind auction is expected to spark significant technology commercialization and growth in the U.S. Additionally, the need for floating wind technologies and other technical complexities specific to California might have acted as important retainers for developers trying to surf this wave of opportunities without the necessary local knowledge or the right partnerships with experienced floating wind technology developers.

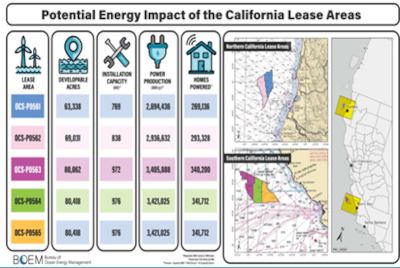

Finally, and in relation to the auction bid dynamics, DNV generally observed a higher level of interest on the Central Coast sites (OCS-P 0563, OCS-P 0564 and OCS-P 0565) during the first day and a final (and more abrupt) bidding price fluctuation on the second day. The Northern California sites (OCS-P 0561 and OCS-P 0562) ended up with the highest acreage prices (see Figure 2). DNV acknowledges that the transmission infrastructure advantages of the Central Coast were likely observed to be of high value, with the port infrastructure and proximity being the ultimate driver of acreage cost by bidders. However, there are multiple dynamics at play.

Here are DNV’s observations of the main identified complexities in California for floating wind deployment:

- The lack of infrastructure (ports and fabrication yards) and supply chain suitable to host and support the different stages of floating offshore wind (FOW) construction (hull fabrication, assembly and integration and other tier 1 components’ logistics at industrial scale). Robust port infrastructure is scarce on the West Coast and is already congested by shipping industry and military activities. Several medium-size ports have expressed interest in upgrading their infrastructures to enable offshore wind development, with varying levels of support and public engagement.

- The lack of track record for floating wind technologies in deep waters, with the water within the five auctioned sites being at unprecedented depths for the global floating wind industry, and significantly deeper than all the existing FOW prototypes. This will require the implementation of innovative mooring systems and cable configurations (suspended cables, shared anchors etc.) which have not been technologically qualified nor tested at scale.

- According to the public measurements, the wind resource in the auctioned areas is slightly scarcer than in the North East, resulting in lower average Net Capacity Factors within the areas auctioned in California with respect to their New York Bight counterparts.

- Power transmission, given the onshore transmission grid status, is insufficient, especially in North California and South Oregon, with extensive investments required to integrate the Offshore Wind capacities planned in these areas. In addition, the distance to shore within the proposed Wind Energy Areas and the associated water depths imply the need for floating substation, which still present several bottlenecks although are considered technically feasible.

- The permitting process remains a significant obstacle. A sensitive ecological environment, significant fishing activity, and an important tribal presence will make the stakeholder engagement and permitting particularly extensive. Moreover, the lack of industry knowledge from most of the socioeconomic sectors implies an additional challenge in terms of permitting, stakeholder engagement, and workforce training.

- Finally, from a very general project development and financing standpoint, there are higher levels of uncertainty within CAISO’s offtake handling procedures as compared to those set in New Jersey or New York. This has likely reduced the potential bidders and further relaxed the bidding prices. Unlike the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities or the New York State Energy Research & Development Authority, California does not have a central entity regulating offshore wind energy procurement. Furthermore, the State’s largest utilities have a certain lack of contractual experience that could be directly applicable to the procurement of such gigawatt-scale projects.

In sum, reduced acreage cost as compared to previous auctions in 2022 can be regarded as the natural tendency within a market that is receiving higher pressures on revenue margins, despite the necessary administrative support offered through policies such as the Inflation Reduction Act.

However, the floating wind segment (and the extended offshore wind industry in general) are rapidly maturing into competitive, robust markets, in which lessons learnt are being incorporated to increase their bankability. This is just the beginning for floating wind in North America.

Javier Molinero works as Sr Project Manager in Floating Wind Projects at DNV’s Offshore Wind team in North America.