Leading the charge

Batteries are powering a new wave in ship engineering: From all-electric vessels to hybrid solutions, an increasing number of newbuilds rely on batteries to reduce emissions, maintenance and fuel costs and comply with current and future environmental requirements.

“There are currently around 200 all-electric or hybrid vessels either in operation or under construction, and that figure has grown from zero over the last four years. As a comparison, there are slightly more than 200 LNG ships sailing or on order today, too, but it has taken around 20 years to reach that figure. Is the world waking up to the potential of electric shipping and batteries? Absolutely. And fast.”

Narve Mjøs, Director, Battery Services & Projects, DNV GL, is unequivocal in his assessment of the impact of batteries in the maritime sector.

“It is a transformational technology,” he states, “in terms of all-electric vessels of course, but also for plug-in hybrid and hybrid ships. I think awareness of the benefits of battery technology is widespread now. To demonstrate that I would say that almost every, if not every, vessel ordered in Norway today either utilizes battery technology or has been assessed for it. The advantages are so compelling that this level of scrutiny is a necessity.”

Win-win technology

So what are the benefits? In short, batteries are a prime enabler for reducing fuel consumption and costs, maintenance, and air emissions. What is more, electric power minimizes noise and vibrations and enhances vessel responsiveness and safety. Batteries allow on-board generator sets to be optimized on higher utilization with reduced fuel consumption and for average rather than peak loads. They can store energy harvested from waste heat recovery, regenerative braking of cranes and renewable energy (such as wind or solar power). In addition, they can optimize propulsion systems using LNG and other eco-friendly fuels, and enhance the performance of emission abatement technologies.

The business case for batteries is strong – which is good news considering the high demand for environmental technologies, as Mjøs explains: “There is growing pressure from both authorities and society in general to move towards decarbonization and sustainable transport,” he notes. “This is manifested in an increasing number of local regulations, in addition to international ones, that set clear requirements for pollution, emissions and environmental stewardship, while the UN is committed to promoting and achieving its high-profile Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).”

Mjøs is quick to point out that while shipping remains the most environmentally friendly transport mode, the energy consumption of ships and their air emissions are high and public perception is shifting to a “more could be done” attitude. Batteries and electric power can help tackle this issue head on.

Mapping progress

From a global perspective Norway is an established leader in electric vessels and battery use. This comparatively small nation was the first to produce an all-electric, zero-emission vessel, Norled’s DNV GL classed car ferry Ampere, in 2014, and now operates close to 40 per cent of the world’s battery-powered ships. A recent DNV GL-supported tender to renew the county of Hordaland’s 20-vessel ferry fleet should help consolidate this position, paving the way for a 900 million euro investment in eco-friendly electric vessels while supporting technology and the charging infrastructure. After Norway, France is a major player with just under 20 per cent of vessels, followed by the US with close to seven per cent. In general, Europe is ahead of other continents in the uptake of battery power. Ferries are the most common vessels to use batteries, ahead of offshore vessels and passenger ships.

This fact touches a critical point: The limitations of battery technology. Every owner of an electric car knows that current batteries restrict the travelling distance to a few hundred kilometres at best. The reason is limited energy density.

Driving change

“The automotive sector, along with consumer electronics, have been key to the development of the battery technology we currently use for marine applications,” explains Benjamin Gully, Senior Engineer, DNV GL. “The lithium-ion chemistry you find, for example, in the battery of a Tesla car or smartphone is similar to that on an electric ferry. This multi-sector engagement is essentially fast-tracking development while driving down the cost of lithium-ion battery cells and making the technology increasingly attractive and accessible. This creates a positive cycle of development and adoption.”

Gully says that while price drops on the scale seen in 2016 (when the cost of lithium-ion cells fell by almost 50 per cent) and 2017 may not be sustainable, prices should continue to fall. Car makers have set a goal of 100 US dollars per kWh by 2020 and, given the speed of development, that appears to be realistic. On the other hand, the demands of maritime applications are different from those of the automotive and consumer arenas.

“There is no one-size-fits-all solution for batteries,” Gully says. “As with most things in life, you have to compromise. For example, in consumer electronics there is huge demand for optimizing the energy density and capacity, while the focus for ship batteries is often on performance – as a vessel requires enormous amounts of power – and an optimal life cycle, as highly stressing performance requirements can easily shorten battery lifetime if not properly accounted for. Unfortunately, you can’t have everything and there is a trade-off between capacity, performance and life cycle. Performing well in one respect can diminish capability in another.”

Cost is a unifying factor across sectors, Gully adds, with all consumers clamouring for more affordable solutions. However, because of their safety, testing and system integration demands, maritime batteries are unlikely to be seen as a disposable power source. Gully notes that with the right technology and engineering, maritime battery life cycles exceeding ten years should now be possible.

Hybrid highlights

Both Mjøs and Gully stress that the battery discussion should not focus exclusively on all-electric vessels. The potential for hybrid ships, which charge their batteries during regular operation and use them to enhance engine performance, and plug-in hybrids, which charge batteries on shore and can entirely run on electric power for specific operations, is far-reaching and compelling.

“For deep-sea shipping, batteries are not an option as the main power source and won’t be for the foreseeable future,” says Mjøs, with Gully adding that aside from the physical size and technology leaps that would make this possible, the cost of such a solution would be several times the cost of the entire vessel itself.

But while all-electric vessels are confined to short-sea operations at present, hybrid solutions can provide flexibility across the board.

Gully cites two examples: Offshore vessels and passenger ships, two very different ship types, can both enhance their performance while cutting emissions and costs by using hybrid technology. This is borne out by two recent DNV GL projects, one with SolstadFarstad and the other with Hurtigruten. SolstadFarstad is converting two PSVs, Normand Server and Normand Supporter, to hybrids in accordance with DNV GL’s Battery Power notation. The 5,300 dwt ships will install 560 kWh batteries to replace a diesel generator, resulting in a 15–20 per cent reduction in emissions. Hurtigruten ordered two 140 m hybrid cruise vessels with battery power supplementing the auxiliary engines for spinning reserve and peak shaving, thereby cutting fuel consumption by 20 per cent. The first vessel, Roald Amundsen, will start operating in 2019.

Positive action

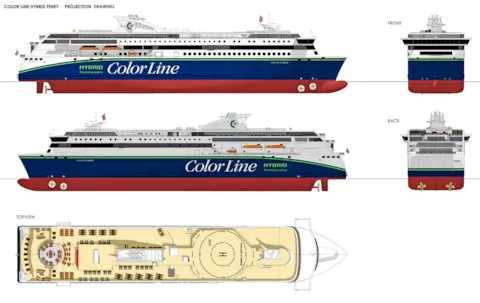

Mjøs is keen to highlight another landmark project: Color Hybrid, due for delivery in 2019 as well. This 160 m, 2,000 pax, 500 vehicle capacity ship is set to be the largest plug-in hybrid ferry in the world once construction is complete at Ulstein Verft.

“Here we have a vessel that is being produced as a direct result of environmental pressure and local action,” explains Mjøs. “The people of the city of Sandefjord in Norway, the home port for the ship, are concerned about unhealthy local air emissions and their impact on the community. So the city’s criteria for new sailing times on the ferry route to Strømstad in Sweden focused on minimizing pollution. As a result the shipowner, Color Line, has ordered a ship that has the ability to sail from and into port under battery power alone, for up to 30 minutes of operation, with absolutely zero emissions and zero noise. This is good for the local population, good for passengers, good for the environment and good for business – which, in a nutshell, sums up the argument for battery technology.”

Mjøs believes the environmental argument will win over an increasing number of decision-makers in the maritime sector, especially as environmental awareness, pressure and regulations spread.

“At the moment there is still a misconception that batteries are only applicable for vessels sailing short, regular routes, such as ferries,” he concludes. “However, as more hybrid solutions are adopted, the industry is beginning to understand the possible applications, opportunities and benefits for vessels across multiple segments and operational parameters.

“Batteries reduce fuel consumption and maintenance costs, cut pollution and, with increasing environmental regulations and requirements that will incur costs for air emissions, provide a very compelling business case. As more and more shipowners wake up to this we expect to see uptake accelerating across the board. The industry is just getting to grips with the power of batteries.”

Narve Mjøs

Director, Green Shipping Programme