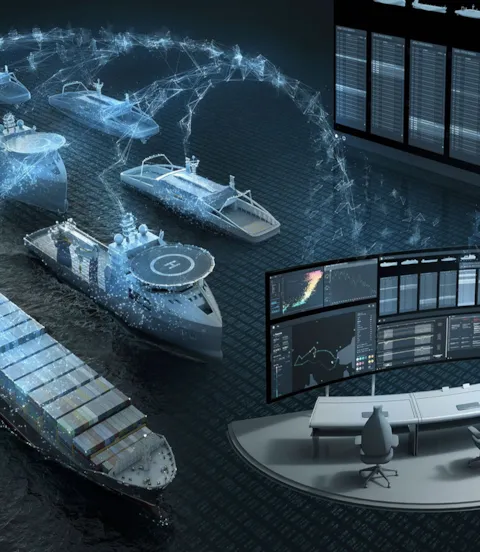

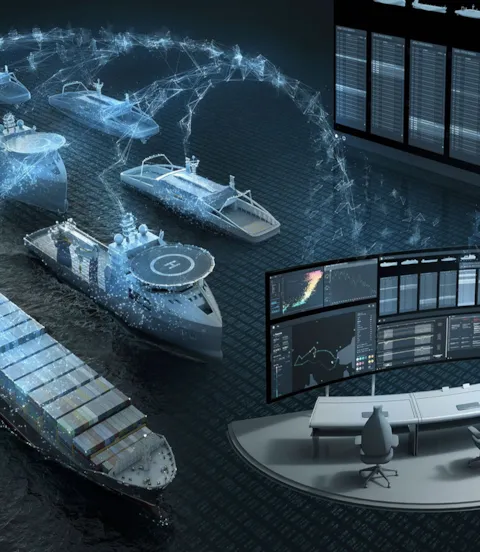

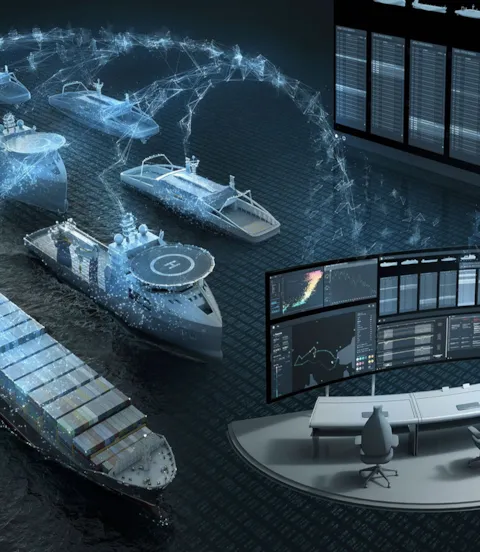

Closing the safety gap in an era of transformation

With all eyes focused on transformations in digitalization and decarbonization, the industry also needs to focus on managing new safety risks that the associated technologies will bring with them, alongside undoubted benefits. A new white paper from DNV reveals safety challenges and provides possible solutions to overcome them.

New white paper addresses emerging safety risks

DNV’s new white paper, Closing the Safety Gap in an Era of Transformation, warns of a looming safety gap between today’s safety risk management approaches and the changing safety risk picture that these transformations will shape within the next five years. In it, DNV explains its current understanding of safety, digital transformation, sustainability and decarbonization.

"The paper is a wake-up call to understand the safety issues that could arise as a result of digitalization and decarbonization to make our industry safer and cleaner," says Fenna van de Merwe, principal consultant at DNV and the paper’s lead author. "Shipowners can use our arguments to help create a sound basis for a transparent, reasoned and informed analysis of digitalization and decarbonization methods, but with safe maritime systems uppermost in their minds. The paper applies to operational vessels and newbuilds and is relevant across a vessel’s life cycle."

Safe maritime systems are the foundation

What is a safe maritime system? The paper defines safety as an ‘emergent property’ of maritime systems that are robust, resilient, and have a process in place for continuous improvement. Safety as an ‘emergent property’ means it is greater than the sum of its parts. In this view, a system is a set of human, organizational and/or technical elements that can achieve things together that each component part cannot accomplish alone.

The paper argues that holistic risk management, including a systemic perspective on safety, is key to managing ‘safety hurdles’ (safety risks) on the road to a more digitalized, carbon-neutral industry.

Safety hurdles during digital transformation

Digitalization offers huge potential to enhance efficiency, safety, and cost controls when applying innovative technology and valuable data. But with all these new technical opportunities, increased system complexity needs to be managed. Software, sensors and machines with control systems that depend on algorithms become interconnected and increasingly reliant upon one another, extracting added value when working in a coordinated manner, but undermining performance and interrupting operations when compromised.

The paper identifies three main safety hurdles associated with this greater system complexity and suggests how to overcome them.

Firstly, as traditional risk management methods become insufficient, there will be a need to focus on system performance in addition to component reliability to manage increasingly complex ship systems. This is because an unreliable system may be safe and a reliable system unsafe. For this reason, it cannot be concluded that a system is safe just because the evidence demonstrates adequate reliability.

Product and process verifications are one means to ensure safe and reliable systems. By using digital twins, all information about the asset is easily available, including dynamic updates on condition and operational parameters. DNV is a partner in the Open Simulation Platform joint industry project where the use of digital twins has been proven as a cost-effective approach to support the design and operations of future maritime systems.

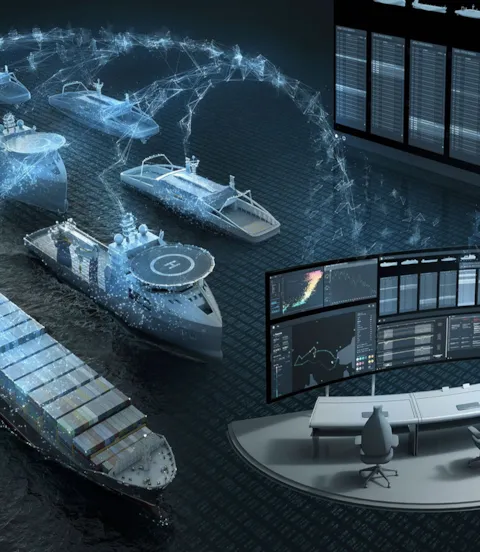

Centralization and dispersed teams will increase

Secondly, digitalization also affects how people will work. On the one hand, increasing automation and remote operation come together with growing centralization of operations. On the other hand, complex and integrated systems involve many different stakeholders to contribute to smooth operations, and lead to more dispersed teams that need to work together. Who is accountable for what? What happens if communication is disrupted, or normally ‘passive’ operators are rapidly called into action?

Companies will therefore need to support people’s roles and needs. This, van de Merwe argues, requires two things. One is human-centred design of systems with technologies that support human performance. The other is balanced ‘function allocation’.

In one example of raising holistic understanding of risk, a DNV-led joint industry project (JIP) on human-centred design of alert management systems addressed challenges related to alarm flooding on the bridge. The project arose from a general consensus that alarms function less well as a decision support tool than they should do, and at times are least helpful when they are needed most. One key conclusion was the need for system integration and human-centred design to provide the operator with the necessary information that they need to make decisions promptly and act appropriately.

Thirdly, as organizations increasingly become a patchwork of multiple stakeholders and suppliers, they need digital transformation strategies for managing emerging risks across the entire organization.

Allocating tasks between people and technology

The paper sees ‘function allocation’, the division of functions between technology and people, as particularly important during digital transformation. This, van de Merwe explains, is because there are potentially fewer people available to intervene if the system’s design does not meet safety requirements or does not work as intended. People adapt better than technology to unknown challenges and use all means, including technology, to handle situations creatively, the paper observes.

In one practical example, DNV has been working with the European Maritime Safety Agency to identify emerging risks and regulatory gaps related to varying degrees of vessel autonomy. This has involved describing how functions should be allocated between the operator and the technical system, followed by risk analysis to evaluate the solution’s safety.

“Clearly, function allocation in digital transformation requires an organization to have or source competence about how digitalization can affect the successful allocation of functions,” van de Merwe points out.

Why do I need a digital transformation strategy?

As digitalization enables safety risk management but also creates new risk, organizations need digital strategies with processes to manage changes resulting from the transformation. Company decisions should support its digital ambitions, drive the organization’s strategic goals, and, importantly, be understood by and communicated to all relevant stakeholders so that there is a unified understanding of the digital risks. “It is important that the transformation processes include a requirement to revisit the strategy frequently in order to keep pace with technological development,” van de Merwe emphasizes. “At DNV we offer a holistic service approach to support our customers on their individual transformation pathways,” Øystein Goksøyr, Head of Department Safety Advisory points out. “We have defined four areas ranging from strategy and smart fleet transformation through to management implementation and smarter operations in which we offer services to ensure the identified opportunities are safe and efficient and are implemented effectively.”

Alternative fuels have specific safety risks

When it comes to decarbonization, existing and pending targets mean the clock is already ticking, creating pressure to make timely choices about realistic pathways to 2050: new, alternative carbon-neutral fuels and the associated fuel systems and infrastructure. International shipping must halve greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2050 to meet International Maritime Organization (IMO) targets and full decarbonization by 2100.

But these new and alternative fuels possess properties that pose new, specific safety challenges when compared with conventional ones, which means that a new understanding and different safety systems and operations are necessary. Ammonia is an exciting alternative, but it is highly toxic and flammable and requires low temperatures. Hydrogen demands extremely low temperatures (–253°C) if stored as a liquefied gas and high pressure (250–700 bar) if stored as a compressed gas. It also has the smallest of all molecules, making it challenging to contain, as well as a wide flammability range and easy ignition.

Safety hurdles during decarbonization

Closing the Safety Gap in an Era of Transformation identifies three main safety hurdles associated with the development of alternative fuels and modes of operation. Firstly, stakeholders may be working in functional silos focused on subsystems. DNV therefore recommends system integration to enable collaboration and transparency.

“DNV leads industry projects that manage the risks associated with specific fuels,” van de Merwe points out. “MarHySafe is one example of where we are working together with industry stakeholders in a joint development project (JDP) to develop a common understanding of hydrogen safety and provide a basis for outlining a road map to hydrogen safety for the maritime industry.”

Missing regulations need joint efforts to close knowledge gaps

Secondly, regulatory frameworks cannot keep up with technological development. “This is why we recommend collective commitment to contribute with knowledge and experience to supplement missing regulations,” van de Merwe explains. “Our classification rules for the use of LNG, fuel cells, methanol, ethanol and LPG are crucial steps towards ensuring safe design to protect vessels against fire and the release of toxic gases through segregation, double barriers, leakage detection and automatic isolation of leakages.”

In a Battery Safety JDP, DNV took the lead in generating knowledge about risks related to batteries in vessels. To further foster the safe operation of ships running on ammonia and hydrogen, DNV is currently developing rules for these fuel options, while working with industry partners to remove hurdles against their uptake, as a partner of the Green Shipping Programme for example.

Thirdly, suppliers and end users may lack maritime and fuel-specific competence. DNV believes the answer here is to develop these competences and a culture of continuous improvement.

Road maps for reducing the safety risks on the way to a safer and cleaner future in maritime

”Our research showed that we need to continue to focus on the people on our way to a safer, cleaner future in maritime,” van de Merwe concludes: “Through breaking down silos we can generate a holistic picture of safety risk and collaborate towards identifying and implementing mitigating measures.” This will help us to be proactive in understanding, defining and meeting the challenges that we need to overcome in order to achieve greater digitalization and decarbonization in shipping.

Fenna van de Merwe

Principal Consultant

- Getty Images/Cultura RF

- DNV

- Getty Images/EyeEm

- Kongsberg Maritime