- Oil and gas

- PERSPECTIVES

- Where’s LNG investment heading?

Where’s LNG investment heading?

Published: 18 December 2020

Writing in LNG Journal, DNV GL’s Hans Kristian Danielsen presents our forecast for a strong outlook for liquefied natural gas (LNG) in the coming decades, and discusses why uncertainty remains in the short term.

- Investors in liquefied natural gas (LNG) face short-term uncertainty amid lingering market effects from the COVID-19 pandemic

- Long-term fundamental drivers of demand for LNG remain in place

- DNV GL’s Energy Transition Outlook 2020 predicts a strong outlook for LNG, as natural gas becomes the world’s largest energy source and is increasingly traded among regions

- This strong outlook would begin with a surge in capital expenditure for LNG during the mid-2020s.

The article first appeared in LNG Journal in October 2020, following the launch of DNV GL’s Energy Transition Outlook 2020 – an independent, model-based forecast of the world's most likely energy future through to 2050.

DNV GL forecasts that natural gas will soon be the world’s largest primary energy source, and that global imports of natural gas between regions will more than double to around 1,685 Gm³/yr by 2035, then stabilizing at this level. A quarter of world gas demand will be traded between net import and net export regions, and much of this will come in the form of LNG. Seaborne trade of natural gas will increase four-fold to 1,680 Mt/yr in 2050.

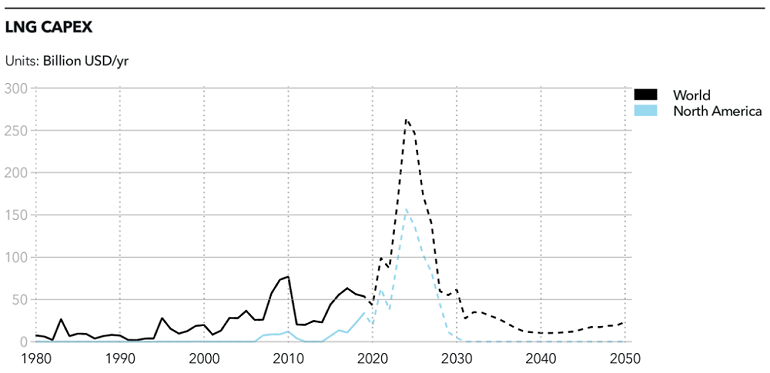

North America is set to lead the sprint in our forecasts, but escalation in the trade war with China could affect this, influencing where the investment is heading (Figure 1). Should this risk not materialize, we forecast that North America will increase liquefaction capacity almost 10-fold over the next decade. Such an expansion would account for three-fifths of a projected LNG capex spike in the mid-2020s. On the demand side, we forecast that the Indian Subcontinent and Greater China are set to dominate LNG imports, accounting for almost half of global regasification capacity.

(Figure 1)

Uncertainties in the short term

International gas prices hit a record low in 2020, as the Covid-19-induced market crash added to existing price pressures, affecting the more immediate outlook for LNG. This is already filtering through as countries fill their storage capacity amid lower demand and cheaper imports. The main question for the future of LNG though, is how this will affect investment?

Last year was a record year for new LNG project approvals. However, with subdued demand in 2020 and increased supply as significant liquefaction capacity came online, some LNG suppliers were immediately exposed to both volume and price risk.

With regasification terminals having filled their storage, some importers have cancelled purchases. For example, in February 2020, as enforced lockdowns spread globally, state firms in China cancelled some cargoes. As the country began to emerge from the first wave of the pandemic, an upturn in economic activity led to a rush to purchase the fuel as LNG prices fell to record lows.

This has led to some LNG cargo cancellations and producers curtailing production. Many LNG projects are based on contracts with fixed prices, which have served to protect the revenues of producers in some cases, but have also led to cancellations as the option left to most buyers is to cancel rather than push for a lower price, aside from buyers on take or pay contracts.

Overcapacity and the direct knock-on effects on production are likely to be short term, though, with our forecasts showing that demand for natural gas, and particularly LNG, are set to rebound quickly in the coming years.

The more significant effects may lie in changes to investment. Short-term challenges have led to final investment decisions (FIDs) on several major liquefaction projects being pushed back, and a number of international projects seeking FID being delayed. Projects have been postponed or delayed in the US1, Canada2, Mozambique3, and Qatar4, among others.

Factors influencing long-term growth and certainty

We forecast that natural gas will take its place as the world’s largest energy source from the mid-2020s – with global gas demand growing to a peak around a decade later.

As the least carbon-intensive fossil fuel, gas can play a prominent role in reducing emissions in the energy transition. Much of this we expect to be led by policy, as countries switch from coal to natural gas in power generation. Gas demand is also set to rise in transport, largely from the world’s shipping fleet increasingly using LNG as a fuel, as well as in manufacturing and for heat in buildings. The potential to later decarbonize natural gas through carbon capture and storage (CCS) and hydrogen, and to use existing gas infrastructure in the process, is also a driver of certainty for natural gas and LNG.

In terms of gas prices, analysis from DNV GL’s Energy Transition Outlook 2020 shows that lower gas prices significantly increase demand for gas, much of which would be met by LNG. Gas demand is sensitive to changes in gas price. We forecast that reducing the gas price by 50% from our forecast would increase the demand for gas production by 22% in 2050. On the other side, a 50% increase in gas price above our forecast would result in a 15% drop in gas demand in 2050.

The price of gas influences the pace at which it replaces coal in the world’s energy system. With a lower gas price, we expect there to be much more demand for gas. In turn, we would expect there to be greater need for the LNG liquefaction capacity additions that have recently been postponed or put on hold due to low gas prices, but the low prices may put pressure on the viability of some liquefaction projects. This suggests LNG investments should go ahead in the longer term, but that short-term overcapacity could delay or affect where the investment is heading.

Where is the investment heading?

As of February 2020, 42 markets were importing LNG and some 20 were exporting, according to International Gas Union (IGU).5

Due to the investment required countries are most likely to invest in infrastructure to export LNG when they have longstanding, significant gas reserves and can source the feed gas for liquefaction at competitive cost. Further, competitive edge is held by producers with a reputation for reliability, and by locations with the shortest shipping routes to Asian markets.

These are the particulars of large exporters such as Australia, Qatar, Russia, and the US, all of which have already made significant investments in LNG. However, the trade war between US and China, as well as increased tensions between Australia and China adds complexity to the commercial picture. Unless these tensions ease there is a risk that American as well as Australian projects will win a lower share of new contract volumes than their commercial offering justifies. This could potentially favour Qatar, Russia and possibly East-African gas projects.

On the regasification side, South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan have previously dominated LNG imports. China is soon to take the lead and India is on a similar trajectory, with significant investment in regasification facilities, but many other markets are also eying increases in regasification capacity, many more countries than are investing in exports. Part of this is that liquefication facilities require multi-billion-dollar investments in facilities, while investments in regasification terminals run in the hundreds of millions.

Some current LNG export regions face growing populations and energy demand and may increasingly use domestic gas reserves for domestic consumption. We forecast South East Asia as a whole to switch from a net gas exporter to a net importer in the 2030s as domestic demand outpaces supply. Malaysia and Indonesia are currently net LNG exporters, but are set to become net importers, for example.

These many import markets suggest an increasingly flexible LNG market, with many sources of demand. Changes in LNG financing will add to this, with stakeholders increasingly taking on their own marketing and selling responsibilities, rather than requiring buyers to purchase minimum quantities of LNG under long-term agreements. These are signs of a strengthening spot market for LNG.

Regional imbalances driving LNG value chains

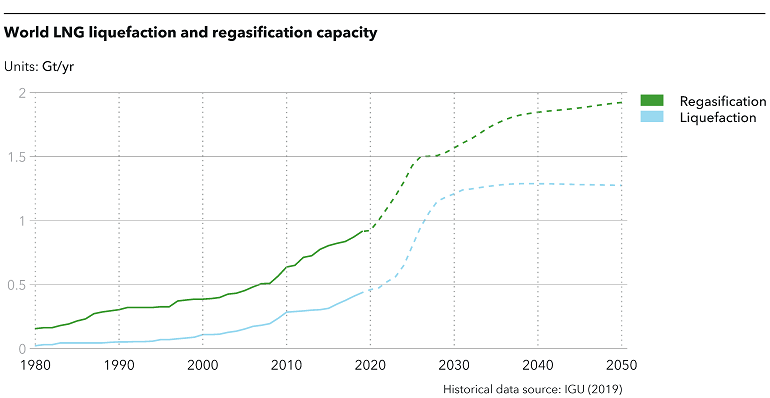

(Figure 2)

We forecast that global capacity for regasification will more than double by 2050 (Figure 2). The Indian Subcontinent and Greater China will produce only a fraction of the gas they consume, accounting for more than 75% of natural gas imports from 2035. With few pipelines supplying the region and little or declining gas production, we expect LNG to meet much of the demand. This necessitates significant increases in LNG regasification capacity, with Greater China set to surge more than five-fold to almost 400 Mt/yr. Likewise, we predict the Indian Subcontinent will see a rapid rise from around 40 Mt/yr in 2018 to more than 500 Mt/yr by 2050.

South East Asia will start from a similar point, increasing six-fold to 240 Mt/yr by 2050. Regasification capacity in Europe will increase moderately to 225 Mt/yr in the mid-2020s.

Supporting this growth in demand, we forecast that liquefaction capacity will triple over the next decade globally to 1,200 Mt/yr, before plateauing until 2050. We predict that North America will account for just under half (560 Mt/yr) of this capacity in 2030. The region would also see the largest growth in liquefaction, accounting for around 44% of global capacity by 2050. Middle East and North Africa will be the second largest, representing about 17% of global liquefaction capacity.

LNG a reprioritization of investment?

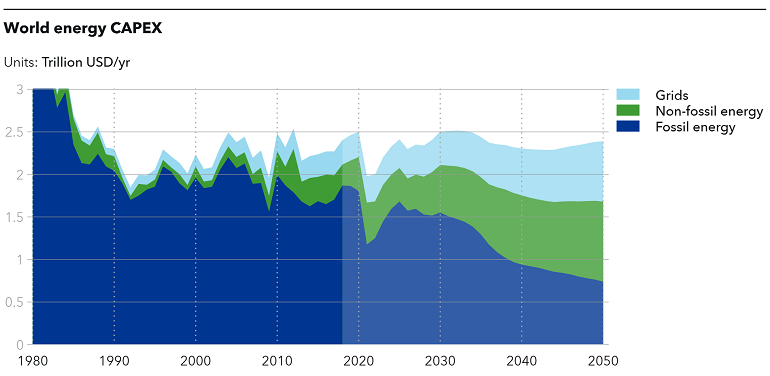

In terms of investment, we forecast that capex in LNG will increase dramatically in the mid-2020s, with North America accounting for three-fifths of the around USD 250 billion (bn) set to be invested in both 2024 and 2025 (Figure 3). The region will account for a similar proportion of the more than USD 170bn in 2027 and USD 140bn in 2028, before global investment falls to USD 60bn, a little higher than in 2018.

(Figure 3)

Total world fossil energy capex is set to fall significantly in the next year. We forecast that it will rebound to 2025 but will still be lower than 2018 levels, taking a different course than the huge increase in LNG capex in these years. In 2024, LNG will account for 17% of world fossil capex and 15% of world fossil capex in 2025, up from less than 4% in recent years. We’ve seen investment delayed at least for 2020, so uncertainty in the short term could affect the timeline. This investment is a sign of reprioritization, as the world shifts towards a future in which natural gas will be the world’s largest primary energy source, with it increasingly traded as LNG across the world’s oceans.

References:

- https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-lng-shell-idUSKBN21H2E9

- https://www.rivieramm.com/news-content-hub/news-content-hub/fidrsquos-delayed-by-global-uncertainty-59073

- https://www.africaoilandpower.com/2020/06/08/fid_on_mozambiques-rovuma-lng-project-delayed-until-2021

- https://www.spglobal.com/platts/en/market-insights/latest-news/natural-gas/040720-qatar-petroleum-delays-start-up-of-north-field-lng-expansion-due-to-covid-19

- https://www.igu.org/app/uploads-wp/2020/04/2020-World-LNG-Report.pdf

Download DNV's Energy Transition Outlook 2020

Sign up to receive PERSPECTIVES

Disclaimer:

DNV prides itself on providing accurate information but makes no claims or guarantees about the accuracy, completeness or adequacy of contents in this publication, and disclaims liability for any errors or omissions. The authors’ views here do not necessarily reflect DNV’s views.